Keyboards Explained

First published: Friday June 24th, 2022

Report this blog

Instruments Explained: Part I

Introduction

Musical Instruments are cool. They are all unique and similar at the same time: have different sizes and shapes, but all of them create music. There are anything from three to six to infinite families of musical instruments. Here are some of them:

String instruments would be any instruments with strings, either plucked or bowed. To change the pitch (note), you press down on the string in different places to make the note sound higher or lower. Some examples include Violins, Cellos, Guitars, and Basses.

Woodwind instruments use air, blown into the instrument via a mouthpiece or reed (or both). To change the pitch (note), you cover holes or buttons, depending on the instrument. There are three mini-families in the woodwind family, with some instruments with no reeds, some with a single reed, and some with a double reed, but I'll explain this later. Some examples of woodwind instruments include Flutes, Clarinets, Saxophones, and Oboes.

Brass instruments also use air, but instead of blowing air, you make sound by buzzing your lips into a mouthpiece. In general, Brass instruments are made out of brass-an alloy created by mixing zinc and copper. Some examples include Trumpets, Trombones, Tubas, and French Horns.

Percussion instruments make sounds when the instrument is struck. Some provide rhythms, like snare drums, bass drums, cymbals, and other types of drums. Others have pitch, or sound, like xylophones and vibraphones, and have a format sort of similar to pianos, in that sharp or flat keys are placed differently (I will explain when I get there).

Keyboards are a little different. Most keyboards have strings that make a sound when they are hit. Technically, this makes them both a string and a percussion instrument. But just for the purposes of this blog, I will count them as a separate family. However, in the four-family system, they are usually part of the string family, but are sometimes considered as percussion instruments.

I will also count guitars and other related instruments as a different family, since, unlike other strings, they are plucked, while strings are bowed most of the time. Also, their posture is much different than strings. But just like keyboards, the are considered strings in the four-family system.

Keyboards

Pianos, Organs, Celestas, and Harpsichords. These four instruments are similar in many ways, but also have some differences. They all have keyboards, but 9 They all incorporate a keyboard system. They all have a similar shape. However, they have some different mechanisms to make a sound. Pianos use a mechanism that results in felt hammers to hit the string(s). Celestas use a sort of similar mechanism, but instead of hammers hitting strings, they are hitting small metal bars. Harpsichords use a different mechanism in which the strings are plucked, sort of. And Electric Pianos use, well, electricity.

Before we get into the instruments, I want to explain the keyboard. All instruments in the Piano/Keyboard family have a keyboard. The Keyboard is the part of these instruments that has black an white keys, arranged in a seemingly random layout. But why is the layout like it is? The reason has to do with Sharps and Flats. In Music Theory, there are seven Naturals and Five Accidentals (Flats or Sharps): C, C#/D♭, D, D#/E♭, E, F, F#/G♭, G, G#/A♭, A, A#/B♭, and B. On a Keyboard, these notes are put in ascending order, starting on A0* on a piano, A0* on a Organ, and F1 on a Harpsichord, on loop, all the way until C8 on a Piano, from F1 to F6 on a Harpsichord, and A0 to something like C7 on the Organ. So A, A#/B♭, B, C, etc.

White Keys are natural notes, meaning that there aren't any sharps or flats. The seven are C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Black Keys are Accidentals (Sharps and Flats). The Black Keys represent sharps and flats. The five are C#/D♭, D#/E♭, F#/G♭, G#/A♭. Why am I putting the slash? Let's take an example: C#/D♭. Sharps (#) are a half step above another note, and Flats (♭) are a half step below another note. What are half steps? Let's go back to the list of notes: C, C#/D♭, D, D#/E♭, E, F, F#/G♭, G, G#/A♭, A, A#/B♭, and B. Two notes are a half step away from each other if they are consecutive. So, C and C#/D♭ are a half step away from each other. But C#/D♭ is also consecutive with D, so those are also a half step away from each other. C#/D♭ is the note that is between C and D, and is a half step above and below C and D, respectively. This is why you can use C# and D♭ interchangeably, because they are the same note. But this brings up another question. Below, I have two sections of a keyboard. On the the left/top is a regular keyboard, one with 7 naturals and 5 accidentals. On the right/bottom is a wrong keyboard, with 7 naturals and 5 accidentals.

In the wrong piano, there are notes that don't exist. In the wrong keyboard, there is a note called B#. B# would be a note that is a half step above B. But if we look back at our real piano, there isn't a note there. This is because B and C are a half step away from each other. This means that B# is the same note as C. Similarly, C♭ is the same note as B. Why? When the "rules" of music were written out, there were the 7 natural notes, but they were unevenly spread out. Flats and Sharps were added later to fill in the gaps. And it just so happened B and C, and E and F, were close enough so no flats or sharps had to be added.

*Numbers represent the octave that the note is in. The lowest hearable octave is octave 0. The numbers go up once the note C has passed. So it goes (A0, A#/B♭0, B0, C0, ... G0, G#/A♭0, A1, B1, etc).

*Maximum Range of the Pipe Organ goes past the range of what humans can hear, theoretically going as low as C-2 and as high as C9 if my research is correct, but these are not hearable by the human ear.

Pianos were invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori, in the early 1700s. They were originally called Pianoforte or Fortepiano, since Pianos could play piano (soft/quiet) and forte (loud). The name was shortened The modern piano has many roots, but I think the most influential is the Harpsichords, because of the similarities. Their shape is similar, they both have strings, they both have keys and many more. However, the way that harpsichords and pianos make sound is different, as harpsichords use a sort of plucking mechanism, but pianos use felt hammers. Anyways, Cristofori was an expert in harpsichord making, and it can be inferred that he could have taken some elements of harpsichords and applied them to pianos, as they have a very similar shape (at least some of them), both are made out of wood, an both have strings Pianos are made out of wood. The type of wood used to make the piano can affect the sound.

Upright pianos are also very similar to grand pianos. The difference is that there is an extra hinge in the Mechanics, which modifies the hardware in a way that instead of the strings being horizontal, like a grand piano, they are vertical. This makes the piano much smaller. Also, the sound quality may not be as good. However the keyboard is the same as a grand piano, but the size and the pedals are a little different.

Electric Pianos are also similar to the other pianos, but with one major difference: they use electricity. When you press down on a key, an electric signal passes through some wires on the inside, causing the speakers to play out a note. Some Electric Pianos have pedals and are in a similar shape to an upright piano, except they use electricity. Some others are flat and are placed on tables, and have no pedals.

Some electric pianos have the ability to make it so that instead of having a piano sound, the speaker will produce sound from another instrument like a trumpet or saxophone. Some others might have the ability to record what you play and play it back. Some others might have a built-in metronome. Some might have two or more of the listed.

Here are Pictures of Grand (Left), Upright (Middle), and Electric (Right) pianos.

But how do pianos create sound in the first place?

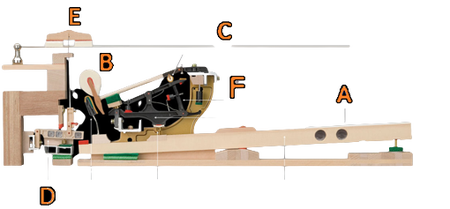

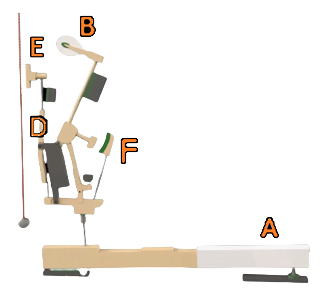

When you press a key on a Grand or Upright, it activates a mechanism to create sound. The mechanism goes like this: the key (A) is sort of like a lever. When you press down on it, the other side comes up. This side is connected to a felt hammer (B). When you press down on a key, the hammer hits three strings (C), causing the string the vibrate, which makes a sound. This also causes the damper level (D) to raise, causing a causing a damper (E) to lift up allowing the string to make a sound. The Damper is a piece of wood with felt at the bottom. It lies on the string until it is lifted. When it is lifted, there is nothing to prevent the string from vibrating, so the sound continues. But when it comes down, When you let go of the key, the damper comes back down, stopping the strings from vibrating, which stops the sound. There's some other hardware, but what I want to focus on is the letter F. I couldn't find the name of it, but this keeps the hammer close to the string so you can play the same note repeatedly. There are also bridges, which keep the strings' pitch relatively accurate, and tuners to tune the strings, or make the strings the correct pitch. This is the mechanism is required to play a single note. Below are two diagrams, one for a grand piano and another for upright pianos. But think about this: pianos have 88 keys, which means that the range of pianos (the amount of notes it can play) is 88. Pianos have one of the largest ranges of all musical instruments. This also means that there are 88 of the mechanics shown below in one piano. This also means that unlike some other instruments, you are able to play several notes at the same time, something that you can't do on many other instruments. Here are two diagrams, One for Grand Pianos, and One for Upright Pianos.

At the bottom of most (if not all) grand and upright pianos, there are pedals (usually three). The pedal that is the furthest right is called the damper/sustain pedal. When you press it, it makes all the dampers go up. This means that if you press a key, the string will keep vibrating until the dampers are put back down, or the string has lost all momentum from the felt hammer. The pedal that is the furthest left is the soft/una corda pedal. Remember when I mentioned that there are three strings per note? When you press down on the soft pedal, the keys and dampers move slightly to the right. This makes the dampers aligned with two of the three strings. The middle pedal has different functions on Grand and Upright pianos. The middle pedal on Grand Pianos and higher-end Upright Pianos are called Sostenuto Pedals. If you play a note, then press down on the sostenuto pedal, the damper will still stay up, kind of like the damper pedal. But all the other dampers are down. This means that some notes will be ringing, while others are going to be shorter. On most Upright Pianos, the middle pedal is a practice pedal, basically, if you press down on it, the sound becomes a little quieter, which is more suited for practicing, since when you are practicing you don't need to be as loud as when you are performing.

The Piano is a very famous instrument, and thus, many famous composers from centuries ago wrote pieces for the piano, and many composers and songwriters from today have wrote pieces for the piano. Not only that, but because of the large range of the piano and the ability to play several notes at once, theoretically, it is possible to play 99.9% of all pieces and songs that have pitch (you will need several arms or at least several people to play some of them, but it is still possible.) The following applies to Grand, Upright, and Electric Pianos, since they have the same range and same notes playable.

In General, you can play just about anything on the piano, and so the piano repertoire is very large.

Harpsichords are very similar to Pianos, but with a few differences. The first is when they were invented. It appears hat the earliest mention of a Harpsichord comes from 1397 in Italy, coming from a man called Hermann Poll, saying that he invented a Harpsichord. The oldest surviving Harpsichord dates back to the early 1500s. Compare that the pianos, invented in the early 1700s.

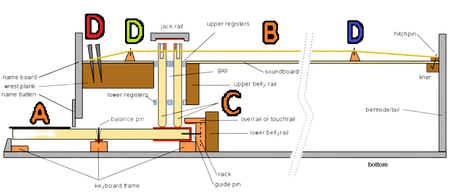

Harpsichords are very similar to Pianos, but with a few differences. The main difference is how they make sound. As I explained, pianos make sound by a felt hammer hitting a string (and some other stuff that won't make the character limit). However in a harpsichord, the sound is made differently. Just like pianos, there are strings in the harpsichord. But the difference is that harpsichords are plucked, not hit with a felt hammer. The Key (A) is, similarly to the piano, sort of a lever. When you press down on it, the other side hits a Jack (C), causing it to come upwards. The top of the jack is made so that when it comes up, it comes in contact with the String (B), which produces sound. This sound is different from a piano in a way I can't really describe, but is because the jack is plucking the strings.

Some harpsichords have two keyboards. This is to give the play some more control, as you can set them to hit different strings. This makes the player more able to add more musicality. Also, Some Harpsichords have a Pedal Keyboard. These are different from Piano pedals because instead of lengthening or shortening a note, it plays a note. The Pedals are connected to strings, usually the lowest and longest strings, producing the lowest sound. These pedals are played with your feet.

The harpsichord's repertoire is almost all Baroque Music. "Classical" Music is split into several time periods; Medieval (1150~1400), Renaissance (1400~1600), Baroque (1600~1750), Classical (1750~1820), Romantic (1820~1900), and 20th/21st century (1900~Present-Day).

Some famous Baroque composers include Johann Sebastian Bach, who wrote Brandenburg Concertos; George Frideric Handel, who wrote Messiah, and Antonio Vivaldi, who wrote the Four Seasons. There is also Christian Petzold, not a Baroque Composer, who wrote Minuet in G, which was mistaken as being written by Bach. The First Three were composed for a Baroque Orchestra, which unlike a modern orchestra, consisted of a Harpsichord. Baroque Orchestras were much smaller, and consisted of much less instruments, as some instruments like Clarinets and Bassoons weren't invented. Also, in this time period, you might see Harpsichords called Cembalos or Clavicembalum. Those are the German and Italian names (respectively) of a Harpsichord.

In the 1960s, a new genre of music was created, Baroque Pop/Baroque Rock. This new genre was a mix of Baroque and Pop/Rock music. As far as I know, it has faded away, but it might come back soon. Besides that and Petzold, I couldn't find any other examples of modern Harpsichord.

Organs are different from pianos and harpsichords. First of all, I would like to point out the fact that Organs (the musical instrument) are completely different than Organs found in the body. I will sometimes use the term "Pipe Organs" as an alternative to Organs (technically, there are also non-piped organs). Anyways, Organs use several keyboards, each with it's own "shape." While Pianos and Harpsichords have strings, but Pipe Organs use air. What happens is that when you press down on a key, air is let in from an electric motor. This air passes through pipes. These pipes are of different sizes. If you play a high note, chances are, the pipe that the air will pass through will be relatively short. But if you a low note, the pipe that the air will pass through will (probably) be very long. Before I get into how long they can be, here is a picture showing how organs make sound.

But that's not all. Organs have several keyboards (typically three or four). Each keyboard has a different voice. In other words, it sounds different, and has a different set of pipes. There is also a pedal keyboards that you press with your feet. There are pedals, sort of like in pianos. But unlike the piano, these pedals don't lengthen the note. Instead, it is another keyboard. You play the keyboard with your feet. The pedal keyboard plays some of the lowest notes possible, which also means that it is connected to the longest pipes.

In this picture, you might see buttons all around the sides of the keyboards. Below is a gif that shows what happens when you press one of the buttons, left/top is dark mode, right/bottom is light mode. The Blue, Gray, and Red lines sticking out represent the buttons. What happens when you press in a button is that it connects to a mechanism shown that lets in air from a pump (top left of the GIF). The air is represented with a turquoise color. This sound passes into the pipes, making sound. Pushing a button in could divert the air in a way that it goes through two pipes. This makes the sound different.

This makes it one of the few keyboard instruments that don't use strings or a percussion system to make sound; it uses air.

Let's put this information together: we have several keyboards, meaning hundreds of keys. Hundreds of keys means hundreds, or sometimes thousands of pipes. Some of these pipes are small, while others are very large. How large? Well, 64 feet tall. For a comparison, the Sphinx in Egypt is 66 feet tall. You can't just go around the city, carrying pipes that are the size of the Sphinx. Organs need to installed, and can't be transported. There are two main places that they can be installed in. The first is churches. (Correct me in the comments if I'm wrong) Some church music is played on organs, and some churches have organs in them.

The second is concert halls. Think about it: if you have a concert hall, there will be many instruments and people performing. The organ is one of those instruments. While many other instruments, like violins and cellos, can be transported around rather easily, Organs cannot, since they are too large. Instead, they need to be put there. Obviously, some (many) concert halls don't have organs, since sometimes there aren't organs performing. But generally the larger, more famous, fancy and/or better the sound quality will be in the concert hall, the greater the possibility that an organ is installed/needs to be installed. You might have heard of some of these before: Vienna's Wiener Musikverein, Boston's Symphony Hall, Amsterdam's Concertgebouw, Berlin's Konzerthaus Berlin, and Tokyo's Opera City Concert Hall. These are some of the best concert halls in the world, and all have organs in them.

Here is a picture of Jordan Hall (taken in 2019). In the back, behind the Christmas Reef, is a Pipe Organ.

AbbreviationsGP is Grand Piano, UP is Upright Piano, EP is Electric Piano, HP is Harpsichord, and OG is Organ | GP | UP | EP | HP | OG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 9.5 |

| Dynamics | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 9.5 |

| Size | 3.5 | 5.5 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 0.5 |

| Uniqueness | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 9.5 |

| Repertoire | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 7.0 | 6.0 |

| Total | 36 | 38 | 42 | 36 | 35 |

One member of the keyboard family I quickly want to mention is the celesta. A celesta is sized like an upright piano. When you press a key, one of those felt hammers that were used in pianos would hit a chime bar. Chime bars can be found in instruments like glockenspiel. You might have heard a celesta in the opening to Harry Potter, Hedwig's theme or in Tchaikovsky's Sugar Plum Fairy Dance. However, besides these two, I couldn't find any other major examples. In general, if someone learns to play the Piano, they can also play the Harpsichord, Organ, and Celesta, because they all use the same keyboard system. However, playing the Organ may be a little different due to the many keyboards and foot pedals.

Back to Top

< th > < details > abreviations < /summary> and for the elements i used < th > (ignore the spaces) i believe

I share the blog to you if you want to see it

Can't play piano tho...

Speaking of which (not really), I find western notes overly complicated. Indian Notes are just the letters S,R,G,M,P,D,N,S(dot on top), and higher or lower is indicated by a dot above or below. Not that I'm good at music tho haha