Should We Follow Social Customs?... according to Utilitarianism

Blog by

Last updated: Tuesday March 26th, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Tuesday March 26th, 2024

Report this blog

+3

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the differences and similarities between the two primary breeds of utilitarianism: 'act' (devised by Jeremy Bentham) and 'rule' (devised by John Stuart Mill). It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

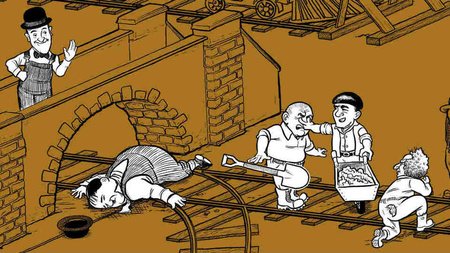

An illustration of an altered version of the trolley problem, in which a man is pushed off a bridge onto a railroad track to stop an incoming train from running over several workers: the act and rule utilitarian approaches differ in their perspective on using murder to actuate the greatest happiness principle

Overview

Utilitarianism is a normative [1] consequentialist [2] ethical system judging the morality of an action based on how ‘pleasant’ or ‘painful’ its outcome is. It is distinct from deontological [3] modes of reasoning, as consequentialism focuses on the states of affairs brought about by the action instead of assessing the morality of the action itself based on specific criteria. Formalised in late-eighteenth-century Britain, utilitarianism is centred on the principle of utility, described by its proponent, the English jurist Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), as ‘that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness’ (On the Principle of Utility) [4]. The work of English economist and political theorist John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) admixed the moral theory with the deontological principle of adhering to social rules of conduct; this established two primary varieties of utilitarianism: ‘act’ (associated with J. Bentham) and ‘rule’ (associated with J. S. Mill).

Act Utilitarianism

Jeremy Bentham expounded on the greatest happiness principle and founded act utilitarianism—an objective [5] methodology fostering moral conduct solely based on the happiness it brings to others. His seminal book: An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation [6] summarises his ideology as: ‘judg[ing] any action to be right by the tendency it appears to augment or diminish happiness […] of the community [and individual]’.

He linked this approach to legal reform; in late eighteenth-century Britain—an era of social transformations wrought by the First Industrial Revolution, the rise of capitalism and early movements for Catholic emancipation—he questioned the viability of certain legislation that had been set in stone for centuries, calling for the revocation of that which did not promote happiness in society but rather existed solely because it suited social convention.

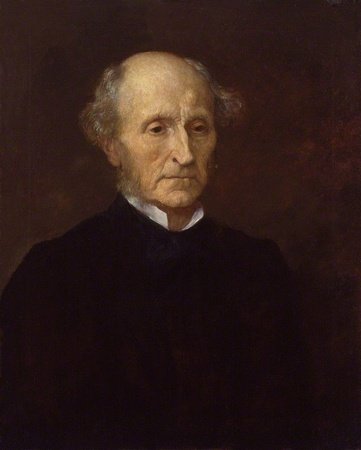

Jeremy Bentham: the founder of act utilitarianism

This ideology is rooted in hedonistic [7] thought, asserting the prevalence of ‘two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure’, deeming pleasure ‘the only good’ and pain ‘the only evil’ (IPML). J. Bentham saw pleasure as an intrinsic human pursuit which should drive one’s every action, irrespective of any societal norm or established ethical principle (criterion), which he dubbed ‘psychological egoism’. To him, pleasure was a quantitative, not qualitative, [8] aspect, always conducive to fostering psychological well-being—‘quantity of pleasure being equal, push-pin is as good as poetry’ (The Rationale of Reward).

However, he did not completely disregard ‘the interest of the community’ (OPU) and devised an algorithm to ensure that one’s pursuit of pleasure does not cause pain to others or oneself: ‘felicific calculus’ [9]. Whilst not a direct set of rules, these seven measures: intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty, propinquity, fecundity, purity and extent, [10] estimate the amount of happiness an action is likely to induce, serving as a standard to ensure the pleasure of the individual and the community and avert the fomenting of pain.

However, he did not completely disregard ‘the interest of the community’ (OPU) and devised an algorithm to ensure that one’s pursuit of pleasure does not cause pain to others or oneself: ‘felicific calculus’ [9]. Whilst not a direct set of rules, these seven measures: intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty, propinquity, fecundity, purity and extent, [10] estimate the amount of happiness an action is likely to induce, serving as a standard to ensure the pleasure of the individual and the community and avert the fomenting of pain.

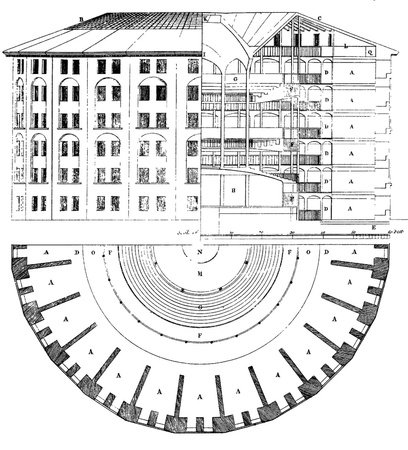

A sketch of the Panopticon: Jeremy Bentham's idea of a perfect prison allowing for a single guard to oversee every inmate without them knowing they are being watched; one of his many hypothetical social reforms, the Panopticon is characterised by a sense of utility in securing absolute discipline; in fact, French philosopher Michel Foucault used J. Bentham's idea as a metonym for the mass surveillance prevalent in society

Rule Utilitarianism

John Stuart Mill staunchly advocated his predecessor’s consequentialist ideals but preferred a qualitative and perceptive assessment of pleasure, giving rise to his system of rule utilitarianism. He placed more emphasis on ‘intellectual’ pleasures and the ‘good to the aggregate of all persons’—a less hedonistic and more community-centred perspective of producing pleasure, as claimed in his keystone book Utilitarianism [11]: ‘Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness … [and] to do as one would be done by, and to love one's neighbour as oneself, constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality.’

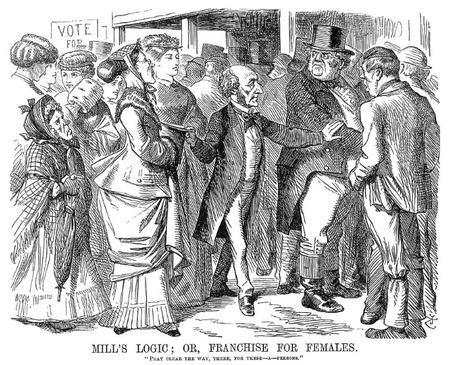

Like his predecessor, J. Bentham, J. S. Mill was concerned about social reform in the United Kingdom. During the zenith of the Chartist Movement, and later, Gladstonian politics [12], he actively advocated women’s suffrage, educational reforms, judicial impartiality and legal equality.

John Stuart Mill: the founder of rule utilitarianism

He connected the utilitarian principle of promoting happiness to the entire community, regardless of individuals’ characteristics (egalitarianism), with libertarian ideals, such that his magnum opus On Liberty claims that: ‘The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others’.

However, J. S. Mill distanced himself from act utilitarianism, instead pursuing a model somewhat more reliant on adherence to social customs deemed moral absolutes, such as obeying road signs, which J. Bentham would not have directly approbated. Nonetheless, he recognised the supposed inflexibility of universal morals—that ‘rules of conduct cannot be so framed as to require no exceptions’ (Uti.). As a compromise, J. S. Mill devised the 'rule': the moral standards of an action—what is deemed ethical or unethical in a particular instance—must serve as a precedent for determining the morality of future actions, loosely based on social etiquette.

Furthermore, he preferred a qualitative, perfectionist assessment of pleasure rather than J. Bentham’s quantitative one, often dubbed ‘swine morality’. J. S. Mill considered sensual, purely hedonistic pleasures not conducive to happiness as they only provide superficial contentment; he insisted that pursuing social pleasures is superior to solely individual ones since they aid the community—an integral utilitarian tenet—and that academic pleasures should always be prioritised. In fact, he wrote that it is ‘better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’ (Uti.).

However, J. S. Mill distanced himself from act utilitarianism, instead pursuing a model somewhat more reliant on adherence to social customs deemed moral absolutes, such as obeying road signs, which J. Bentham would not have directly approbated. Nonetheless, he recognised the supposed inflexibility of universal morals—that ‘rules of conduct cannot be so framed as to require no exceptions’ (Uti.). As a compromise, J. S. Mill devised the 'rule': the moral standards of an action—what is deemed ethical or unethical in a particular instance—must serve as a precedent for determining the morality of future actions, loosely based on social etiquette.

Furthermore, he preferred a qualitative, perfectionist assessment of pleasure rather than J. Bentham’s quantitative one, often dubbed ‘swine morality’. J. S. Mill considered sensual, purely hedonistic pleasures not conducive to happiness as they only provide superficial contentment; he insisted that pursuing social pleasures is superior to solely individual ones since they aid the community—an integral utilitarian tenet—and that academic pleasures should always be prioritised. In fact, he wrote that it is ‘better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’ (Uti.).

A cartoon displaying J. S. Mill's support for women's suffrage and equality of the sexes, in general: his utilitarian ethics disposed regarding every individual as having equal value since under the greatest happiness principle, the pleasure brought about by an action is considered equal regardless of who is affected; therefore, J. S. Mill concluded that if men were granted suffrage to secure their political freedom, women must be bestowed the same right

Model Example

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of the Second World War demonstrates the difference between act and rule utilitarianism in whether or not to justify 'extreme' [13] measures to bring about happiness—namely, murder. By August 1945, US President Harry S. Truman had decided to deploy a then–indefinite number of atomic bombs on industrially significant Japanese cities to intimidate the Japanese government into surrendering to the Allied forces, thereby ceasing the Second World War.

Mindful of the potentially morbid scale of lives this novel technology could cost, but also of Japan's obstinate refusal to concede, President Truman regarded an immediate end to the war as the only way to prevent casualties from further piling up, irrespective of how violent or 'extreme' the means would be. Indeed, the magnitude of nuclear bombs' impact on Japan—hundreds of thousands were killed and Hiroshima and Nagasaki rendered uninhabitable—coerced the nation to surrender.

Harry S. Truman: authorised the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on utilitarian grounds

In retrospect, historians generally agree that President Truman's decision saved more lives than it cost and hence caused more 'good' (pleasure) for American and Japanese soldiers/civilians. This was his aim: abiding by the act utilitarian perspective of the greatest happiness principle, he defied social rules of conduct (in condoning murder) to bring about net pleasure to the community. Many, especially rule utilitarians, remain opposed to the President's decision on moral grounds.

Act utilitarians laud President Truman's perspective as pragmatic and compliant with J. Bentham's idea of fostering happiness in the community regardless of social convention. Since the President's intentions were legitimate and concordant with 'the greatest good for the greatest number', convention and etiquette needed to be countered. US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara agreed: 'He was trying to save our nation [the United States]. And in the process, he was prepared to do whatever killing was necessary'. This approach is highly quantitative, focusing on the number of individuals subjected to the action's pleasure rather than the quality of said pleasure. For instance, President Truman did not extensively consider the psychological pain wrought by the fear of atomic bombs dominant in the Cold War era, which undermined the pleasure wrought by the reduction of military casualties (in terms of felicific calculus, fecundity).

Rule utilitarians deem the decision as imprudent and unjustified since it countered the rules of conduct and set a dangerous precedent for the potential future use of the atomic bomb. As it did not abide by a concrete 'rule'—that murder can never be resorted to in producing pleasure—some perceive President Truman as unobservant. He seemed solely concerned with the immediate impact of deploying nuclear bombs on Japan and not the consequences of future nuclear warfare [14]. Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy wrote: 'In being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children'. Likewise, some draw parallels to General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea during the American Civil War, in which a scorched earth tactic was implemented to capture Savannah, resulting in the death of countless civilians—some even consider it a war crime. This could have inspired President Truman to resort to mass murder as well during the Second World War; nonetheless, the result of both was conducive to swift military success. Disagreement about whether or not his utilitarian decision was ethical seems guaranteed to persist for many generations.

Act utilitarians laud President Truman's perspective as pragmatic and compliant with J. Bentham's idea of fostering happiness in the community regardless of social convention. Since the President's intentions were legitimate and concordant with 'the greatest good for the greatest number', convention and etiquette needed to be countered. US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara agreed: 'He was trying to save our nation [the United States]. And in the process, he was prepared to do whatever killing was necessary'. This approach is highly quantitative, focusing on the number of individuals subjected to the action's pleasure rather than the quality of said pleasure. For instance, President Truman did not extensively consider the psychological pain wrought by the fear of atomic bombs dominant in the Cold War era, which undermined the pleasure wrought by the reduction of military casualties (in terms of felicific calculus, fecundity).

Rule utilitarians deem the decision as imprudent and unjustified since it countered the rules of conduct and set a dangerous precedent for the potential future use of the atomic bomb. As it did not abide by a concrete 'rule'—that murder can never be resorted to in producing pleasure—some perceive President Truman as unobservant. He seemed solely concerned with the immediate impact of deploying nuclear bombs on Japan and not the consequences of future nuclear warfare [14]. Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy wrote: 'In being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children'. Likewise, some draw parallels to General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea during the American Civil War, in which a scorched earth tactic was implemented to capture Savannah, resulting in the death of countless civilians—some even consider it a war crime. This could have inspired President Truman to resort to mass murder as well during the Second World War; nonetheless, the result of both was conducive to swift military success. Disagreement about whether or not his utilitarian decision was ethical seems guaranteed to persist for many generations.

The destruction wrought as a consequence of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: act utilitarians perceive them as conducive to the reduction of military casualties—to the greatest happiness of the public—whereas rule utilitarians deem them unjustified since the rules of conduct were countered, seemingly permitting murder to be resorted to at a whim

Conclusion

Characterised by the sole dedication to the individual and community’s general welfare irrespective of universal morals and social convention, utilitarianism posits that ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation’ (J. Bentham). It is bifurcated into ‘act’—deeming the principle of utility and quantitative pleasures as an action’s sole aim—and ‘rule’—prioritising consideration for rules of conduct and qualitative pleasures.

The primary distinction between the two modes of utilitarian thinking is observed in their approach to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings. Whilst act utilitarians condone President Truman's decision since it likely saved lives, and hence abided by the greatest happiness principle of bringing net pleasure to the community, rule utilitarians reject it as it countered the social principle 'rule' of not murdering—the means were unjustified. Queensborough Community College summarises the difference between act and rule utilitarianism as follows:

'the act utilitarian measures the consequences of a single act. The rule utilitarian measures the consequences of the act repeated over and over again through time as if it were to be followed as a rule whenever similar circumstances arise'.

Notes

[1] A 'normative' philosophical concept assesses the morality of social customs and norms, social behaviour and social standards/rules of conduct. It is closely tied to normativity—the phenomenon of societies collectively labelling certain actions as 'good' or 'bad'. For instance, most societies believe that pain should be avoided.

[2] In normative ethics, consequentialism is the evaluation of an action by its consequences and the general impact it leaves on others, rather than by specific criteria or by intention. Its opposite is deontology.

[3] In normative ethics, deontology is the evaluation of an action based on a specific set of social/individual criteria held to be absolute and universal (i.e., applying to every action, regardless of the circumstances), rather than by its consequences. Its opposite is consequentialism.

[4] The name 'On the Principle of Utility' is hereafter abbreviated as 'OPU' for simplification purposes.

[5] An objective moral system applies to every action and functions the same with every individual since it is based on a set of metrics by which happiness is measured (felicific calculus). However, there is still a hint of subjectivity in considering the amount of joy brought about and the number of people affected, especially if felicific calculus is disregarded.

[6] The name 'An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation' is hereafter abbreviated as 'IPML' for simplification purposes.

[7] In ethics, a hedonistic system is ultimately aimed at causing pleasure; for act utilitarianism—to the greatest number of people.

[8] 'Quantitative' refers to the amount of pleasure, or the number of individuals affected by the action, whilst 'qualitative' refers to the quality of pleasure—in terms of how lasting, valuable, useful, et cetera, it is.

[9] 'Felicific calculus' is also known as 'utility calculus', or 'hedonistic calculus'.

[10] The listed principles of felicific calculus are defined as follows, each referring to the pleasure and pain of an action: intensity is its strength, duration is its length, certainty/uncertainty is its likelihood of occurring, propinquity is the amount of time until it occurs, fecundity is the action's probability of producing the desired pleasure, purity is the action's probability of not producing the opposite effect (therefore, pain), and extent is the number of individuals it affects.

[11] The name 'Utilitarianism' (in reference to J. S. Mill's book) is hereafter abbreviated as 'Uti.' for simplification purposes.

[12] 'Gladstonian' refers to UK Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, who served four non–consecutive terms from 1868 to 1894. As the first prime minister of the Liberal Party, he brought about a slew of social reforms towards education access, Irish Home Rule, electoral integrity, et cetera.

[13] In this context, 'extreme' refers to unusual means often deemed unethical in a social context, as is murder.

[14] However, President Truman did not approbate nuclear warfare and deemed the use of atomic bombs as 'murder' which must be avoided in all but desperate circumstances. In fact, he refused to deploy a third bomb to depose the Japanese Emperor Hirohito and avoided mention of them during the Korean War.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories.

ACT UTILITARIANISM

- Alfange Jr., Dean. (1969). “Jeremy Bentham and the Codification of Law”. Cornell Law Review vol. 55, no. 1: pp. 58–77. Available online.

- Bentham, Jeremy. (1789). Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation § On the Principle of Utility. Reproduced on BCcampus.com. Available online.

- Driver, Julia. (2022). "The History of Utilitarianism" § Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Eggleston, Ben. (2017). "Act utilitarianism". PhilPapers. University of Western Ontario. Canada.

- Miller, Jacques-Alain; Miller, Richard. (1987). “Jeremy Bentham’s Panoptic Device”. October vol. 41: pp. 3–27. Available on JSTOR.

- Plamenatz, John P.; Duignan Brian; et al. "Jeremy Bentham". Encyclopedia Britannica

- "Philosophy 302: Ethics: The Hedonistic Calculus". philosophy.lander.edu . Lander University, South Carolina. United States.

RULE UTILITARIANISM

- Anschutz, Richard Paul. "John Stuart Mill". Encyclopedia Britannica

- Driver, Julia. (2022). "The History of Utilitarianism" § John Stuart Mill. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Mill, John Stuart. (2001). On Liberty. Batoche Books Limited. Ontario, Canada. Available online.

- Mill, John Stuart. (2009). Utilitarianism. The Floating Press. Available online.

- Pontes, Ariel. (December 24, 2020). "Rule utilitarianism: Should we ever break rules for the greater good?". Medium.

- Turner, Edward Raymond. (1913). “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England”. The American Political Science Review vol. 7, no. 4: pp. 588–609. Available on JSTOR.

- "Philosophy 302: Ethics: The Hedonistic Calculus". philosophy.lander.edu . Lander University, South Carolina. United States.

THE ATOMIC BOMBINGS

- Hamby, Alonzo L. "The decision to use the atomic bomb". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Lackey, Douglas P. (1982). “Missiles and Morals: A Utilitarian Look at Nuclear Deterrence”. Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 11, no. 3: pp. 189–231. Available on JSTOR.

- Thomas, Evan. (June 3, 2023). "The Bomb Was Horrifying. The Alternatives Would Have Been Worse.". Foreign Policy.

- "Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Independence, Missouri, United States.

GENERAL

- Cartwright, Mark. (2023). "Social Change in the British Industrial Revolution". World History Encyclopedia.

- Duignan, Brian; West, Henry R.; et al. "Utilitarianism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Haines, William. "Consequentialism" § Basic Issues and Simple Versions. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . University of Hong Kong. China.

- Nathanson, Stephen. "Act and Rule Utilitarianism". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Northeastern University, Massachusetts. United States.

- Pecorino, Philip A. "Chapter 8: Ethics: Utilitarianism". Queensborough Community College. New York, United States

- Veenhoven, Ruut. (2004). “Happiness As an Aim in Public Policy: The greatest happiness principle”. Positive Psychology in Practice § Chapter 39. Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The Netherlands. Available online.

- "Normative ethics". New World Encyclopedia.

- "Social Life in Victorian England". philosophy.lander.edu. University of Delaware, Delaware. United States.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning UTILITARIANISM. The rest can be accessed from my Utilitarianism and Kantianism series.

I believe it means something between noice and nice

R there any mistakes in the quiz if u tell me i can contact the quizmaker