Ethics 101 - The Greek Philosophers

Last updated: Friday February 2nd, 2024

Report this blog

- Overview

- The Sophists: Introduction

- The Sophists: Protagoras and Moral Relativism

- The Sophists: Gorgias and Moral Nihilism

- Socrates: Introduction

- Socrates: The Soul

- Socrates: Moral Absolutism

- Socrates: 'The Good Life'

- Socrates: The Socratic Method

- Socrates: Opposing the Sophists

- Aristotle: Introduction

- Aristotle: The Role of Reason

- Aristotle: The Function of Humans

- Aristotle: The Golden Mean

- Aristotle: Opponents of His Virtue Ethics

- Epicurus: Introduction

- Epicurus: Materialistic Thought

- Epicurus: Moderate Hedonism

- Epicurus: Opponents of Epicurean Thought

- Summary

- Limitations of this Blog

- Why this Blog is (Mostly) Ideal for Students

- Further Reading

Overview

Due to this blog's sheer length, I have provided a summary of the main points.

I would suggest checking out the Additional Notes section beforehand.

The Sophists: Introduction

The Sophists (derived from ‘sophia’, meaning ‘wisdom) were itinerant teachers specialising in the art of rhetoric, language, and public discourse. They travelled throughout major cities adjacent to the eastern Mediterranean Sea, flourishing in the second half of the fifth century BCE (the Athenian Golden Age). The most eminent were Protagoras, Gorgias, Thrasymachus, and Hippias.

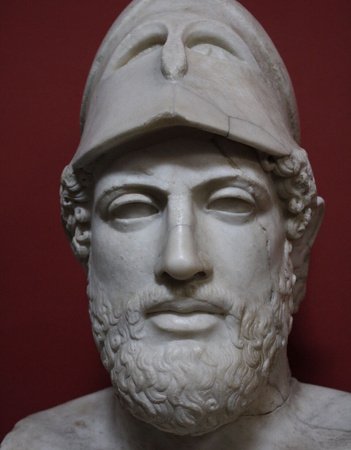

Their fame was brought about by two factors: the declining philosophical interest in the nature of existence – which had intrigued yet divided many thinkers – and the fostering of democracy under Athenian king Pericles. Consequently, active participation from citizens in the ecclesia and the ability to defend oneself in law courts became vital aptitudes, and many resorted to the Sophists to learn how to triumph in debate. Even the social definition of areté (excellence) had transcended from physical strength to rhetorical persuasion.

The Sophists: Protagoras and Moral Relativism

The Sophists' moral relativism is centred around the indispensable quote: “Man is the measure of all things, of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are not, that they are not” – meaning that the individual is the unchanging source of value and knowledge, rather than a deity or moral code.

The above statement is the most distinguished of Protagoras (c. 490-420 BCE): the most celebrated and significant Sophist. He migrated from his hometown of Abdera, in Thrace, to Athens, at the zenith of the city’s golden age. He devised a puissant vocabulary system to win debates and court cases (‘orthoepeia’) and preached these techniques – especially to male youths. He taught that to produce a sound argument, one had to depend on coercively communicating it, not its veracity or logical/moral justification.

"Man is the measure of all things, of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are not, that they are not" - Protagoras

In fact, despite his discredit to universal morality, Protagoras was pragmatic and approbated a legal system to preserve order in Athens: his sole contention was that the same code could not be invoked in other nations, for they had a differing perception of ethics. Due to his belief that law is built on social custom rather than epistemological reasoning, he remained conservative in his outlook on the actualisation of moral relativism in society.

The Sophists: Gorgias and Moral Nihilism

Gorgias (483-375 BCE) could be seen as the laudable right-hand man to Protagoras, supporting the mantle of moral relativism and leading Sophism to indispensable cultural value in Athens. However, whilst Protagoras was a moral relativist, Gorgias was a moral nihilist, postulating that no knowledge or truth can exist. His beliefs are encompassed in his declaration in ‘On the Non-Existent’ that: “Nothing exists; even if something exists, nothing can be known about it; and even if something can be known about it, knowledge about it cannot be communicated to others.”

After migrating to Athens from Leontini, in Eastern Sicily, he initiated his lectures on rhetoric. Gorgias’ passion was the art of speaking, believing it is the foremost factor of any argument. Gorgias reprobated using ‘pathos’ (emotional appeal) in rhetoric, seeing that ‘ethos’ (ethical appeal) and ‘logos’ (logical appeal) were more effective. His insistence on the magnitude of an argument’s conveyance rather than its contents can be traced to his radical attitude to knowledge.

"Nothing

exists; even if something exists, nothing can be known about it; and even if

something can be known about it, knowledge about it cannot be communicated to

others" - Gorgias, 'On the Non-Existent'

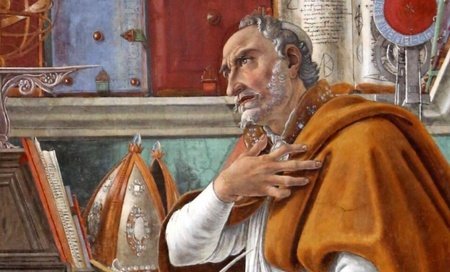

Socrates: Introduction

Socrates’ fame as one of the most distinguished humans – not just of his era but of all time – can be attributed to his maverick attitude to philosophy and his distinct attitude to preaching it. He was a martyr of his cause: dedicating his life to inculcating society with the means to a ‘good life’ and deducing knowledge through meticulous and cogent debate. Unfortunately, it was for being a true philosopher - for oppugning his nation’s tradition and conventions to seek the truth – that led him to take his own life following a guilty court verdict.

Socrates: The Soul

Socrates’ theory of the soul is the epicentre on which his ideas concerning ethics and knowledge are based. Perhaps inspired by Heraclitus, he believed that the physical realm is in a state of flux – distinct from the ideal one comprising the immutable universal values such as wisdom, beauty, and morality (collectively referred to as ‘Truths’). The soul is an immortal segment of the ideal realm: it is the ‘gateway’ through which humans can comprehend objective Truths. However, being bound to a ‘physical’ body, the soul must be maintained by living a principled life, to attain “communion with the unchanging” (Phaedo). This is reached through evaluating one’s knowledge – as wisdom and virtue are interdependent.

Socrates: Moral Absolutism

In conjunction with the unequivocal Truths, one can discern a singular moral system dictating what is right or wrong, as morality forms part of the Truths. Socrates was a moral absolutist, proclaiming the existence of objective ethical aspects one must follow to fulfil the soul, which anyone can uncover. These are gradually manifested upon accumulating sufficient expertise on how to act accordingly and by scrutinising one’s behaviour – fundamentally, learning ethics. The more one knows, the more appropriately they act; therefore, knowledge and morality are linked. This is represented in the adage: “The unexamined life is not worth living”, signifying that, without ‘examining’ one’s conscience and questioning their ethics, they cannot approach the moral truth.

"The unexamined life is not worth living" - Socrates, in Plato's 'The Apology'

Socrates: 'The Good Life'

Socrates’ concept of ‘The Good Life’ is built on the precept that knowledge leads one to live righteously. Every human acts to maximise his delectation; therefore, happiness can be prescribed as the end goal in life. The means to be content is safeguarding the soul, which can be acquired with fixed ethical tenets. Since morality is interconnected with knowledge, acting rationally and assessing one’s beliefs and behaviour guides them to a fulfilling existence.

Since virtue and knowledge are equated, a similar connection can exist for vice; for instance, some break the law for personal gain. Socrates accentuates the difference between a factually good action and one that merely appears to be so – one that causes superficial happiness but does not benefit the soul. Hence, vice is induced by a misconception – a lack of knowledge (ignorance). For example, a thief may commit theft with the intention of self-gratification, but – being an immoral action – it does not sustain the soul; hence does not actually indulge the person.

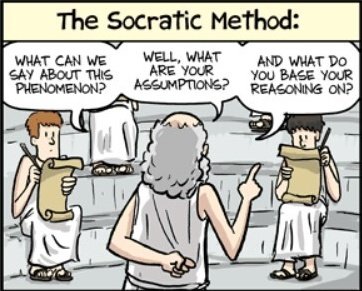

Socrates: The Socratic Method

A gladdening life revolves around knowledge: an objective truth deduced through logic and evidence that applies to every related circumstance. Thus, the application of knowledge to a concept prompts its definition. To ratiocinate a theory, opinion or solution, Socrates taught that one must deduce their accordant definitions – this is done through a dialectic conversation between two individuals (although it can occur with a sole individual’s assenting and dissenting takes on the hypothesis). This is known as the Socratic Method, serving as ‘intellectual midwifery’: means to facilitate the deduction of knowledge.

"The only true wisdom is in knowing that you know nothing" - Socrates, in Plato's 'The Apology'

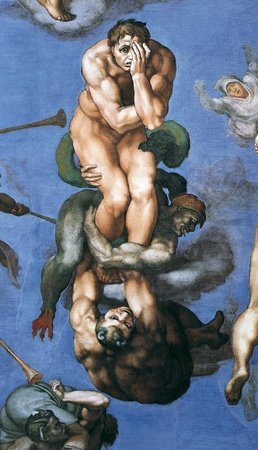

Socrates: Opposing the Sophists

Socrates’ notions seem anathema to the Sophists’ relativism – which, in fact, exhibited one of his intentions as a philosopher. He was one of their most vociferous opponents – repelling their notions that morality and knowledge are relative to the individual's senses and that language is the determining factor of a trenchant argument and disparaging their lofty fees and nigh apathy for tradition (in some cases). However, they converged on their shared sceptic attitude – none sufficed with intuitively accepting social customs and leaving thoughts and authority unquestioned. This outlook wrought Socrates' allegations of being aligned with Sophistry – more specifically, of subverting Athenian youths with orders to challenge the gods’ veracity. Such impiety led to his famous trial, culminating in his decision to take his own life by consuming a lethal dose of hemlock.

Aristotle: Introduction

Aristotle was arguably the most influential Western thinker in Classical Greece – founding the fields of biology, formal logic and primitive psychology. Born in 384 BCE in Stagira, in Ancient Greece, Aristotle’s notions of virtue ethics emanated from his time at the Academy, where Plato tutored him in philosophy. He wrote over 200 treatises in his life, devising such theories as logical syllogisms, taxonomic classification, the scientific method and virtue ethics.

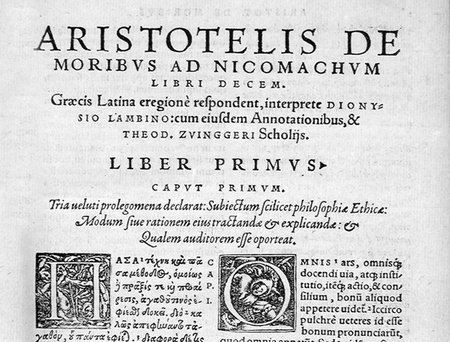

As an advocate for empiricism, he sought to involve sensory knowledge, not just reason, in his work – essential for his advances in scientific understanding. Aristotle’s treatise ‘Nicomachean Ethics’ delineates the four cardinal virtues: prudence, temperance, courage, and justice, and illustrates how these must shape one’s character. His virtue ethics emphasise the necessity of balance in one’s actions (The Golden Mean) and pragmatism in exercising morals (‘phronesis’), owing to the human’s unique rationalism – guiding him to the contentment of the spirit (‘eudaimonia’).

Aristotle: The Role of Reason

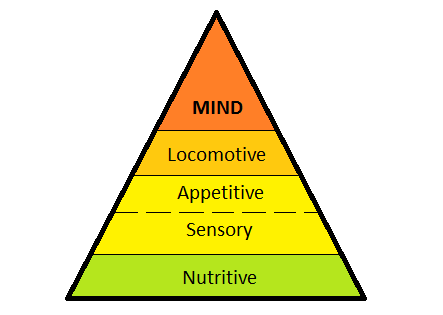

The ability to reason is the lynchpin of Aristotle’s virtue ethics. The human’s competence in ‘deliberative imagination’ (advanced cognition) allows for his path to a fulfilling life. Aristotle described the soul as "the definitive formula of a thing's essence" ('De Amina'), and that of humans is characterised by intellect and reasoning. ‘De Anima’ also demarcates the three types of souls possessed by different organisms: ‘vegetative’ (the simple) allows for living, ‘sensitive’ (the intermediate) permits living and sensing, and ‘rational’ (the complex) capacitates living, sensing and thinking.

The human soul is bilateral, being divided into two segments – housing a conflict between wisdom and desire. Its first segment is the ‘irrational’ component, comprising the vegetative and appetitive parts, which bestow the individual with the desire for biological sustainment and fulfilment of sensory desires, respectively. The second is the ‘rational’ component, which aims at reason. The conflict between these components raises the issue of morality, empowering one to develop principled traits to live a satisfied life of areté (excellence).

Aristotle: The Function of Humans

Aristotle's theory of morality centres around his belief that humans have a distinctive function to fulfil; their end goal is happiness through “[controlled] activity of the soul in accordance with virtue.” (‘Nicomachean Ethics’). Human action is influenced by desire – emanating from the irrational component – and reason or righteousness – resulting from the rational component. As a 'rational animal', one must strive to 'control the soul' by dominating its irrational segment – through exercising reason. Therefore, to effectuate one’s function, ethics guided by reason should be prioritised over desire.

"[The] human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue, and if there are more than one virtue, in accordance with the best and most complete" - Aristotle, 'Nicomachean Ethics'

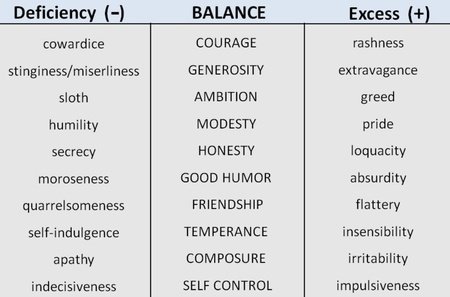

Aristotle: The Golden Mean

In pragmatically exercising virtues compliant with 'phronesis', a middle path must be sought. Every virtue must be practised in balance – in a middle ground between excess and deficiency. In every human action, one must moderate the extent to which it is done; for example, one must eat a suitable amount for sufficient nourishment (mean) and not too little (deficiency) or too much (excess) as to cause health complications. Dubbed the ‘Golden Mean’, Aristotle expounds on four cardinal virtues, from which (approximately) eleven are derived, existing as the “Middle state between [pairs of extremes]” (‘Eudemian Ethics’). An example is honesty, which lies between the deficiency of secrecy and the excess of loquacity.

"[E]xcess and defect are characteristic of vice and the mean of virtue; for men are good in but one way, but bad in many" - Aristotle, 'Nicomachean Ethics'

Aristotle: Opponents of His Virtue Ethics

Aristotle’s virtue ethics met criticism by several prominent Greek philosophers. Plato and Aristotle both held that happiness through moral living is the human’s ultimate goal, but their ethical ideas differed. Plato postulated the existence of a virtual realm containing the ideal renditions of virtues (Forms) which can never be attained. Humans are limited to the illusory realm (the physical world) that includes imperfect variations of the Forms. Since varieties of the same object, such as hair colour, exist, there must be the perfect Form of hair colour on which earthly models are based: “If particulars are to have meaning, there must be universals”. Therefore, the same must apply to morals.

Aristotle – a pioneer of experimentation and proponent of the credibility of sensory experience – dismissed his master’s Theory of Forms. He expressed the lack of necessity for an ‘ideal realm’, as virtues are existent here, in the physical world. For instance, hair colour is innate in every individual; every colour is perfect. Similarly, humans can attain 'ideal' morals by living a virtuous life complying with reason.

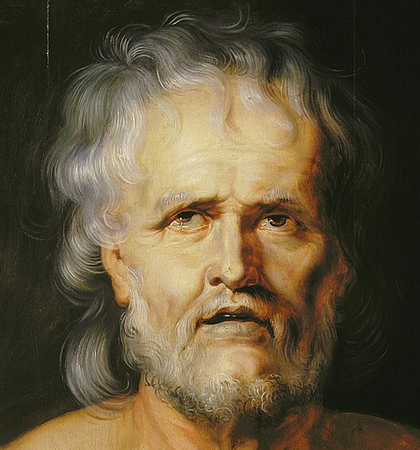

Epicurus: Introduction

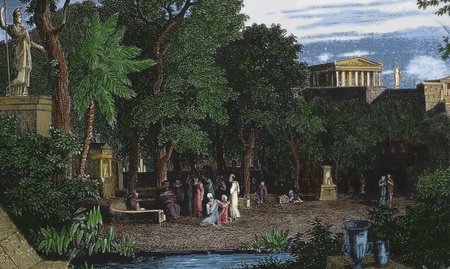

Born in the Greek colony of Samos shortly before the Hellenistic period, Epicurus (c. 342-270 BCE) is one of the most prolific hedonistic thinkers, pioneering a leading post-Aristotelian school of thought alongside Stoicism, Scepticism, Neo-Platonism and Cynicism. During the decline of Greek society following the Macedonian conquests, citizens lost a sense of personal direction, and ethical philosophy shifted in focus from the benefits of the general public to those of the individual. To Epicurus, the lack of a personal (affecting the present universe) spiritual force proves the necessity to seek regulated pleasure as the final aim in life.

He founded a community of disciples based in his garden, with members devoting themselves to pursuing simple pleasures and eliminating excessive desires. Manifestly, the actual idea of Epicurean hedonism (philosophy based on pleasure-seeking) differs from the modern definition of the term, associated with overindulgence. Indeed, Epicurus sought to live a simple life with a diet of bread, cheese and olives, a few close friends, and the eternal companionship of philosophy.

Epicurus: Materialistic Thought

An exponent of materialistic metaphysical thought, Epicurus deduced the basis of all existence to atoms. Exposed to Democritus’ – the founder of the atomist school of thought – teachings in his teens, he subscribed to his notions, positing that only elementary, immutable and ‘uncuttable’ bodies (‘atoms’) and void make up the universe. Since nothing can emerge from nothing, a constituent, uniform form of being must have always existed. Every object is composed of this substance; the varying arrangement of atoms gives rise to different objects. Therefore, given that every article is a compound of smaller segments, it can theoretically be split until its smallest element is derived; it cannot be divided infinitely as ‘nothingness’ would result. For instance, a gold bar can be dissected repeatedly until a constituent gold atom is sourced. With this natural theory as a foundation, Epicurus sought to replace teleological (based on purpose) clarifications of phenomena with mechanistic (based on determinism) ones.

Epicurus concluded that no supernatural force exists, meaning that no universal virtues or god must be abided by. Hence, one’s own benefit must be sought above all, claiming “self-sufficiency [to be] the greatest of all wealth”. Every form of existence must be material, resulting in the impossibility of an afterlife, as the body’s atoms would merely disperse and not transition to another realm. However, death should not be of concern, seeing that “when we are [conscious], death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not [conscious]” (‘Letter to Menoeceus’).

Epicurus: Moderate Hedonism

Seeing that pleasure is the final goal, Epicurus advocated a temperate hedonistic lifestyle; he defined a ‘pleasant’ life as having “the absence of pain in the body and of troubles in the soul”. Humans naturally seek gratification above all, of which there are three categories: natural and necessary (such as basic food), natural and unnecessary (such as lavish food), and vain (such as fame). The first and second pleasures are interrelated, but the latter is a pampered form of the former – a ‘want’ rather than a ‘need’. Since humans suffice with consuming basic foodstuffs, such as bread and water, the necessity of consuming steak and wine is invalid. Human appetite is equally satiated through either bread or steak; therefore, one must be content with simple rather than luxurious goods – “He who is not satisfied with a little, is satisfied with nothing”.

"He who is not satisfied with a little, is satisfied with nothing." - Epicurus

Epicurus: Opponents of Epicurean Thought

Epicurus’ materialistic ethics – specifically his notions on death and god – met criticism from several prolific thinkers. His primary rivals – the Stoics – claimed that the inevitability of death should constantly be meditated, but Epicurus maintained that such a thought invariably leads to irrational fear. Eminent Stoic Seneca also highlighted the necessity of basing life on adherence to virtue rather than pleasure – “Let virtue lead the way: then every step will be safe” (‘De Vita Beata’). They also believed that displeasure should be embraced to fortify one’s character, such that Epictetus asserted that “faced with pain, you will discover the power of endurance” (‘Enchiridion’). Epicurus countered the prevalence of virtue as counter-intuitive, as humans naturally seek pleasure but not morality; therefore, regulated gratification must be prioritised and pain averted.

Summary

PROTAGORAS

- Moral relativism – no universal ethical system; morality and knowledge are individually determined and change with each individual

- Most prominent Sophist – engrossed in rhetoric and developed a powerful vocabulary system to succeed in debate

- Agnostic, did not believe in the gods

- Firm believer in the rule of law and wanted Athenians to follow traditional and religious customs

- "Man is the measure of all things"

- "About the gods, I am not able to know whether they exist or do not exist"

GORGIAS

- Moral nihilism – no moral or objective truth; knowledge cannot be communicated faithfully, so does not exist

- Believed that the moral contents of an argument were irrelevant, superior language use determined the best argument

- "Nothing exists; even if something exists, nothing can be known about it; and even if something can be known about it, knowledge about it cannot be communicated to others."

SOCRATES

- Two realms: the physical one in which humans reside, and the ideal one with unchanging universal values ('Truths')

- The soul: the gateway to attaining the Truths

- Moral absolutism – the Truths are objective ethical values achieved by maintaining the soul and living virtuously

- Interrelation of virtue and knowledge – through growing in wisdom, one can become more principled

- 'The Good Life' – examining one's conscience, scrutinising one's behaviour and questioning one's moral values leads to the fulfilment of the soul

- Vice is brought about by a lack of virtue and is not genuine happiness

- The Socratic Method (dialectic) – knowledge is sourced through seasoned and meticulous debate in the form of a dialogue

- General premises are gradually specified to reach definitions of a concept; Socratic irony and Elenchus are implemented to facilitate this

- Opposed and disparaged the relativistic Sophists

- "The unexamined life is not worth living."

- "I cannot teach anyone anything, I can only make them think."

- "The only true wisdom is in knowing that you know nothing."

ARISTOTLE

- Categories of the soul: vegetative, sensitive, and rational; humans uniquely possess a rational soul

- Human soul is divided into the irrational (vegetative and sensitive) and rational components, leading to a conflict

- Due to their capacity to reason analytically and ethically, humans' function is to live a virtuous life by dominating the irrational segment

- One must strive for happiness by actively practising reason in improving one's behaviour and mentality, guided by principles; leads to 'eudaimonia'

- The Golden Mean – exercise virtues in moderation, between a deficiency and excess

- Aristotelian thought counters Plato's Theory of Forms and Epicurean hedonism

- “All men by nature desire to know.”

- "[Happiness is the controlled] activity of the soul in accordance with virtue.”

- "[Act in the] middle state between [pairs of extremes]”

EPICURUS

- Metaphysical materialism – everything is composed of indivisible bodies 'atoms' which remain eternally and universally unchanged

- Absence of the supernatural since everything is material; no active god, no universal virtues, no afterlife

- One must not fear god or death

- Moderate hedonism – the end goal in life is serenity through living moderately and according to human nature

- Three types of pleasure: natural and necessary, natural and unnecessary, and vain; one must almost exclusively pursue the first variety

- Unnecessary and vain pleasures do not lead to satisfaction; force one to yearn for unnatural objects such as luxury

- Desires should be eliminated to live a simple, virtuous life with simple belongings

- Epicurean thought counters (some aspects of) Stoicism and theological thinking

- “When we are [conscious], death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not [conscious].”

- "[Pleasure is] the absence of pain in the body and of troubles in the soul.”

- "He who is not satisfied with a little, is satisfied with nothing.”

Limitations of this Blog

I must make it explicit that this blog – despite being elongated – is not the definitive guide to Greek ethics, as it only tackles five thinkers. Whilst briefly mentioned, Plato, the Stoics, the Cynics and Neo-Platonists are not covered, as they do not pertain to the Maltese (my native country) Philosophy syllabus, on which I have based this blog. Furthermore, I understand that many Philosophy students would also require some information on the subject's other branches: metaphysics, epistemology, political theory, et cetera, but this blog solely tackles ethics, except for the section regarding Epicurus. Besides having some limitations for students, many 'common' folk (non-students) may find some concepts difficult to grasp since I have attempted to condense information as much as possible; otherwise, the character limit would be well-exceeded. Nonetheless, I request anyone who does not understand a particular idea – be it a theory or a mere word – to ask for an explanation in the comments, and I will do my best to clarify.

Why this Blog is (Mostly) Ideal for Students

Whilst being limited in certain aspects, as a Philosophy student, I highly encourage my equals – from College, Sixth Form or University – to refer to this blog for these reasons, mostly related to essay writing:

- The detail provided should suffice in inscribing lengthy essays.

- The inclusion of examples and quotes help to substantiate the explanations.

- The blog's division into sections including images makes it relatively easy to follow and read.

- The information covered is verified by my tutor (who has a doctorate), rendering it 'safe for use'.

- Due to the comments section, one may freely ask questions if they have any doubts, and their calls will be answered as quickly as possible.

- This may be the only (or one of very few) blog or article covering Greek ethics in such depth, so one is left with no choice but to consult mine!

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog.

PROTAGORAS

GORGIAS

SOCRATES

- Brittanica

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Collector

- Pursuit of Happiness

- Delphic Philosophy (YouTube)

ARISTOTLE

- Brittanica

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Wikiquote

- Pursuit of Happiness

- Crash Course (YouTube)

EPICURUS

- Brittanica

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pursuit of Happiness

- Einzelgänger (YouTube)