Should We Aim at Pleasure?... according to Utilitarianism

Blog by

First published: Monday April 8th, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Monday April 8th, 2024

Report this blog

+4

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the core tenets of utilitarianism (in Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill's theories) and notable counterarguments. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

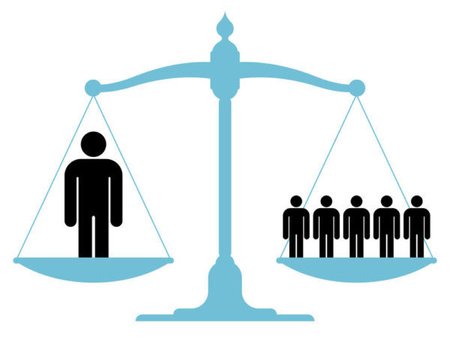

Illustration of the greatest happiness principle: utilitarian modes of reasoning aim at the felicity/pleasure of the largest number of individuals, rather than that of oneself

Overview

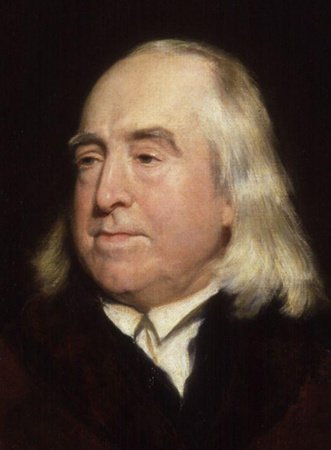

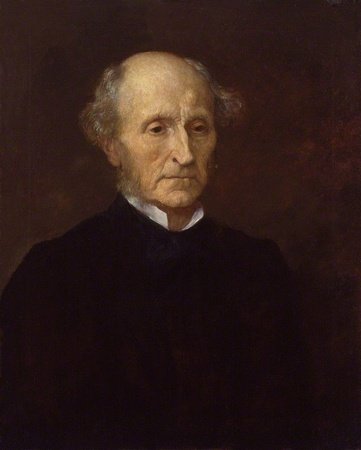

Utilitarianism is a normative [1] consequentialist [2] ethical system judging the morality of an action based on how ‘pleasant’ or ‘painful’ its outcome is. It is distinct from deontological [3] modes of reasoning, as consequentialism focuses on the states of affairs brought about by the action instead of assessing the morality of the action itself based on specific criteria. Formalised in late-eighteenth-century Britain, utilitarianism is centred on the principle of utility, described by its proponent, the English jurist Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), as ‘that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness’ (On the Principle of Utility) [4]. The work of English economist and political theorist John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) admixed the moral theory with the deontological principle of adhering to social rules of conduct; this established two primary varieties of utilitarianism: ‘act’ (associated with J. Bentham) and ‘rule’ (associated with J. S. Mill).

Greatest Happiness Principle

Utilitarianism’s cornerstone tenet is the greatest happiness principle: a hedonistic [5] mode of reasoning aiming at ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ (J. Bentham). In his seminal book, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation [6] Jeremy Bentham asserts the prevalence of ‘two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure’, deeming pleasure ‘the only good’ and pain ‘the only evil’.

To him, pleasure is an intrinsic human pursuit which should drive one’s every action, irrespective of any established ethical principle (criterion) or absolute, which he dubbed ‘psychological egoism’. Hence, moral social conduct must be based on the happiness it brings to others—an objective [7] methodology: ‘judg[ing] any action to be right by the tendency it appears to augment or diminish happiness […] of the community [and individual]’ (IPML).

Jeremy Bentham: the founder of the greatest happiness principle and act utilitarianism

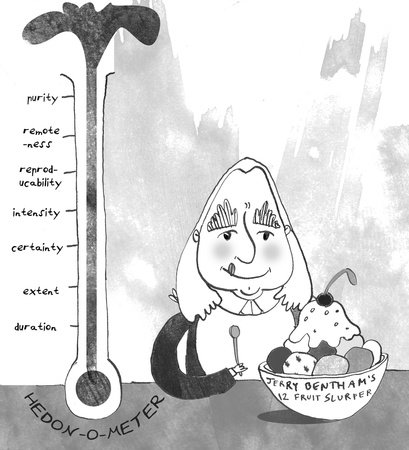

To calculate the pleasure of an action, J. Bentham devised an algorithm to ensure that one’s pursuit of pleasure does not cause pain to others or oneself: ‘felicific calculus’ [8]. Whilst not a direct set of rules, these seven measures: intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty, propinquity, fecundity, purity and extent, [9] estimate the amount of happiness an action is likely to induce, serving as a standard to ensure the pleasure of the individual and the community and avert the fomenting of pain.

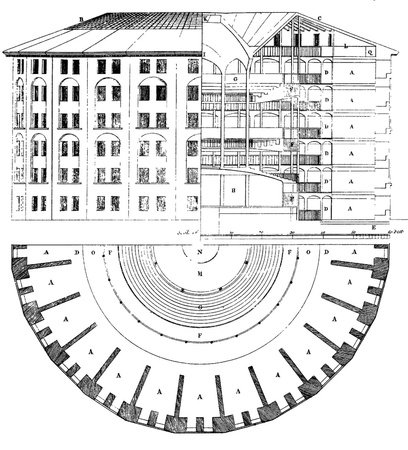

A sketch of the Panopticon: Jeremy Bentham's idea of a perfect prison allowing for a single guard to oversee every inmate without them knowing they are being watched; one of his many hypothetical social reforms, the Panopticon is characterised by a sense of utility in securing absolute discipline; in fact, French philosopher Michel Foucault used J. Bentham's idea as a metonym for the mass surveillance prevalent in society

Social Reform

Owing to its emphasis on ‘the interest of the community’ (OPU), utilitarianism is closely knit to social justice and reform towards the ‘good to the aggregate of all persons’ (J. S. Mill). J. Bentham linked this approach to legal reform in late eighteenth-century Britain—an era of social transformations wrought by the First Industrial Revolution, the rise of capitalism and early movements for Catholic emancipation.

He questioned the viability of certain legislation that had been set in stone for centuries, calling for the revocation of that which did not promote happiness in society but rather existed solely because it suited social convention. J. S. Mill’s perspective of social customs is, likewise, community-centred, as claimed in his keystone book, Utilitarianism [10]: ‘Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness … [and] to do as one would be done by, and to love one's neighbour as oneself, constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality.’

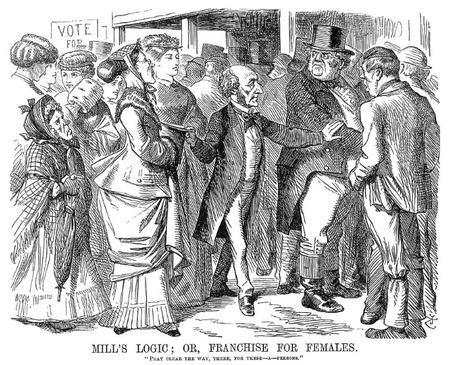

John Stuart Mill: the founder of rule utilitarianism and advocate for social reform

Like his predecessor, J. Bentham, J. S. Mill was concerned about social reform in the United Kingdom. During the zenith of the Chartist Movement, and later, Gladstonian politics [11], he actively advocated women’s suffrage, educational reforms, judicial impartiality and legal equality. J. S. Mill connected the utilitarian principle of promoting happiness to the entire community, regardless of individuals’ characteristics (egalitarianism), with libertarian ideals, such that his magnum opus On Liberty claims that: ‘The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others’.

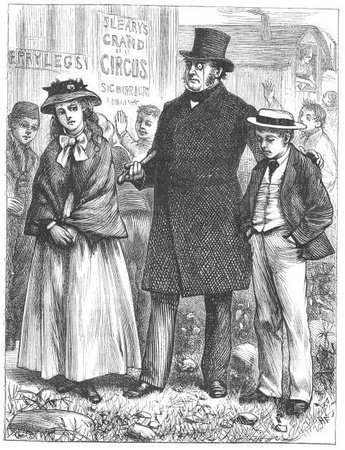

A cartoon displaying J. S. Mill's support for women's suffrage and equality of the sexes, in general: his utilitarian ethics disposed regarding every individual as having equal value since under the greatest happiness principle, the pleasure brought about by an action is considered equal regardless of who is affected; therefore, J. S. Mill concluded that if men were granted suffrage to secure their political freedom, women must be bestowed the same right

Act and Rule Utilitarianism

Whilst both consequentialist and hedonistic, J. Bentham and J. S. Mill’s utilitarian approaches diverged on several principles, such that they can be categorised into two different systems: act and rule utilitarianism. Their primary difference is the consideration of social rules of conduct in one’s actions.

J. Bentham, the founder of act utilitarianism, dismissed the significance of social convention and basic rules of etiquette, perceiving them as obstacles to attaining pleasure for the community. An action should not be judged based on the merits of prior actions or ethical precedents but solely on the derived ‘pain’ or ‘pleasure’. For instance, many societies assert that promises must not be broken under any circumstance, but if doing so would lead to the happiness of others, J. Bentham agreed that this rule of conduct should be neglected.

An illustration of Jeremy Bentham's theory of felicific calculus

Contrastingly, J. S. Mill, the founder of rule utilitarianism, argued that social conventions that have historically proven to safeguard the public’s pleasure must generally be adhered to. For instance, road signs must be followed as they protect drivers’ safety; J. Bentham would not have directly approbated this. Nonetheless, J. S. Mill recognised the supposed inflexibility of universal morals—that ‘rules of conduct cannot be so framed as to require no exceptions’ (Uti.).

As a compromise, he devised the 'rule': the moral standards of an action—what is deemed ethical or unethical in a particular instance—must serve as a precedent for determining the morality of future actions, loosely based on social etiquette. Queensborough Community College summarises this distinction between act and rule utilitarianism as follows: ‘The act utilitarian measures the consequences of a single act. The rule utilitarian measures the consequences of the act repeated over and over again through time as if it were to be followed as a rule whenever similar circumstances arise’.

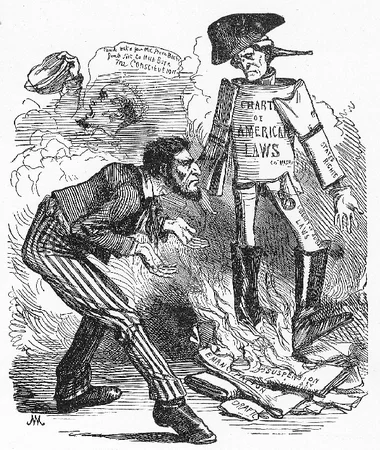

A historical example encapsulating this difference is President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, a constitutional right allowing detained individuals to challenge their confinement in court. In 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War, President Lincoln learned that some Maryland officials were preparing to sabotage Union (the United States) railway networks and aid the Confederate cause. Fearing an internal rebellion was imminent, he suspended habeas corpus to maintain order and keep the Union united in its efforts against the Confederacy, despite US Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney deeming it unconstitutional [12] [13].

Act utilitarians argue that President Lincoln’s decision was morally justified as a particular law—the right to protest one’s detainment—was threatening the community’s security and hence could not be abided by—an obstacle to the happiness of the greatest number. Rule utilitarians contend that the abnegation of a legal principle was morally indefensible as it would set a dangerous precedent for future presidents to do the same at a whim.

As a compromise, he devised the 'rule': the moral standards of an action—what is deemed ethical or unethical in a particular instance—must serve as a precedent for determining the morality of future actions, loosely based on social etiquette. Queensborough Community College summarises this distinction between act and rule utilitarianism as follows: ‘The act utilitarian measures the consequences of a single act. The rule utilitarian measures the consequences of the act repeated over and over again through time as if it were to be followed as a rule whenever similar circumstances arise’.

A historical example encapsulating this difference is President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, a constitutional right allowing detained individuals to challenge their confinement in court. In 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War, President Lincoln learned that some Maryland officials were preparing to sabotage Union (the United States) railway networks and aid the Confederate cause. Fearing an internal rebellion was imminent, he suspended habeas corpus to maintain order and keep the Union united in its efforts against the Confederacy, despite US Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney deeming it unconstitutional [12] [13].

Act utilitarians argue that President Lincoln’s decision was morally justified as a particular law—the right to protest one’s detainment—was threatening the community’s security and hence could not be abided by—an obstacle to the happiness of the greatest number. Rule utilitarians contend that the abnegation of a legal principle was morally indefensible as it would set a dangerous precedent for future presidents to do the same at a whim.

A cartoon displaying Abraham Lincoln's seeming apathy towards the authority of the US Constitution, in direct reference to his suspension of habeas corpus: act utilitarians argue it was justified considering the social circumstances at the time, whilst rule utilitarians argue it was morally unwarranted and perilous

Furthermore, act and rule utilitarian views on the necessity of the quality of pleasure deviated. To J. Bentham, pleasure was a quantitative, not qualitative, aspect, always promoting psychological well-being: ‘quantity of pleasure being equal, push-pin is as good as poetry’ (The Rationale of Reward) [14].

On the other hand, J. S. Mill preferred a qualitative, perfectionist assessment, emphasising ‘intellectual’ pleasures, regarding sensual, purely hedonistic pursuits not conducive to happiness as they only provide superficial contentment. He insisted that pursuing social pleasures is superior to solely individual ones since they aid the community—an integral utilitarian tenet—and that academic pleasures should always be prioritised. In fact, J. S. Mill wrote that it is ‘better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’ (Uti.).

On the other hand, J. S. Mill preferred a qualitative, perfectionist assessment, emphasising ‘intellectual’ pleasures, regarding sensual, purely hedonistic pursuits not conducive to happiness as they only provide superficial contentment. He insisted that pursuing social pleasures is superior to solely individual ones since they aid the community—an integral utilitarian tenet—and that academic pleasures should always be prioritised. In fact, J. S. Mill wrote that it is ‘better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’ (Uti.).

An etching of a privileged couple playing push-pin: despite its seemingly perfunctory nature, J. Bentham still considers it pleasurable since it is a form of entertainment intended to provide amusement

Counterarguments to Utilitarianism

The main opposition to utilitarianism stems from the deontological school of thought, spearheaded by the German Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) belief that one’s actions should be conducted and assessed by their proximity to moral absolutes, not by their consequences and resulting pleasure. In Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals [15], he affirmed the necessity of categorical imperatives—unconditional moral obligations—as a collective fundamental ethical system: ‘I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.’

The same work establishes the principle of 'Kingdom of Ends' forming part of the categorical imperative structure: individuals must intrinsically be treated as the ends on which pleasure must be subjected, not as instruments to achieve pleasure. In other words, contrary to utilitarian thought, no one must be harmed to secure the happiness of others.

Immanuel Kant: the chief opponent of utilitarianism

I. Kant thought that judging actions based on the happiness induced is unreliable and inconsistent—overly dependent on a posteriori reasoning which can easily devolve into immoral actions. He preferred the supposed consistency of wholly adhering to universal morals in guaranteeing a moral action: ‘duty […] lies, prior to all experience, in the idea of a reason determining the will using a priori grounds’ (GMM). J. S. Mill countered the cruciality of categorical imperatives in claiming the unfeasibility of always basing one’s actions on established social customs, which often proved immoral.

Other criticisms of utilitarianism highlight the sheer complexity and impracticality of applying felicific calculus to one’s every action. Charles Dickens notably based the antagonist in his 1854 novel Hard Times, Thomas Gradgrind, on J. Bentham’s system of memorising the seven variables of utilitarianism and continuously analysing their presence; he persistently indoctrinates schoolchildren with this mentality: ‘You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them’. J. S. Mill rejected the purported unattainability of happiness under a utilitarian lifestyle, as it is the rigidness of social structures and unwillingness to sacrifice one’s pleasure for that of others that render it practical, which can be remedied with the infusion of more social solidarity.

Other criticisms of utilitarianism highlight the sheer complexity and impracticality of applying felicific calculus to one’s every action. Charles Dickens notably based the antagonist in his 1854 novel Hard Times, Thomas Gradgrind, on J. Bentham’s system of memorising the seven variables of utilitarianism and continuously analysing their presence; he persistently indoctrinates schoolchildren with this mentality: ‘You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them’. J. S. Mill rejected the purported unattainability of happiness under a utilitarian lifestyle, as it is the rigidness of social structures and unwillingness to sacrifice one’s pleasure for that of others that render it practical, which can be remedied with the infusion of more social solidarity.

"Thomas Gradgrind Apprehends His Children Louisa and Tom at the Circus": a cartoon displaying the rigidness of Thomas Gradgrind in Charles Dickens' novel Hard Times; his overly analytical approach

Conclusion

Characterised by the sole dedication to the individual and community’s general welfare irrespective of universal morals and social convention, utilitarianism posits that ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation’ (J. Bentham). It is bifurcated into ‘act’—deeming the principle of utility and quantitative pleasures as an action’s sole aim—and ‘rule’—prioritising consideration for rules of conduct and qualitative pleasures.

Whilst praised for its emphasis on aggregation (deeming others’ pleasure an integral part of the individual’s pleasure), egalitarianism and objectivity, many criticise its sole focus on hedonism, which may lead to immoral actions—namely, deontologists (such as Immanuel Kant), claiming adherence to categorical imperatives to be the most cohesive ethical system. Charles Darwin, in The Descent of Man, professes the efficacy of utilitarianism in safeguarding the individual and community’s felicity, as perceived by J. Bentham and J. S. Mill:

‘As all men desire their own happiness … and as happiness is an essential part of the general good, the greatest happiness principle indirectly serves as a nearly safe standard of right and wrong.’

Notes

[1] A 'normative' philosophical concept assesses the morality of social customs and norms, social behaviour and social standards/rules of conduct. It is closely tied to normativity—the phenomenon of societies collectively labelling certain actions as 'good' or 'bad'. For instance, most societies believe that pain should be avoided.

[2] In normative ethics, consequentialism is the evaluation of an action by its consequences and the general impact it leaves on others, rather than by specific criteria or by intention. Its opposite is deontology.

[3] In normative ethics, deontology is the evaluation of an action based on a specific set of social/individual criteria held to be absolute and universal (i.e., applying to every action, regardless of the circumstances), rather than by its consequences. Its opposite is consequentialism.

[4] The name 'On the Principle of Utility' is hereafter abbreviated as 'OPU' for simplification purposes.

[5] In ethics, a hedonistic system is ultimately aimed at causing pleasure; for act utilitarianism—to the greatest number of people.

[6] The name 'An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation' is hereafter abbreviated as 'IPML' for simplification purposes.

[7] An objective moral system applies to every action and functions the same with every individual since it is based on a set of metrics by which happiness is measured (felicific calculus). However, there is still a hint of subjectivity in considering the amount of joy brought about and the number of people affected, especially if felicific calculus is disregarded.

[8] 'Felicific calculus' is also known as 'utility calculus', or 'hedonistic calculus'.

[9] The listed principles of felicific calculus are defined as follows, each referring to the pleasure and pain of an action: intensity is its strength, duration is its length, certainty/uncertainty is its likelihood of occurring, propinquity is the amount of time until it occurs, fecundity is the action's probability of producing the desired pleasure, purity is the action's probability of not producing the opposite effect (therefore, pain), and extent is the number of individuals it affects.

[10] The name 'Utilitarianism' (in reference to J. S. Mill's book) is hereafter abbreviated as 'Uti.' for simplification purposes.

[11] 'Gladstonian' refers to UK Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, who served four non–consecutive terms from 1868 to 1894. As the first prime minister of the Liberal Party, he brought about a slew of social reforms towards education access, Irish Home Rule, electoral integrity, et cetera.

[12] The US Supreme Court never officially collectively ruled on President Lincoln's decision; rather, the US Circuit Court of Appeals in Maryland, led by Chief Justice Roger Taney, ruled against it, in Ex parte Merryman.

[13] Some historians have argued that the suspension of habeas corpus was not unconstitutional since another provision in the US Constitution (the Suspension Clause) allowed it 'in extraordinary circumstances: when a rebellion or invasion occurs and the public safety requires it to be', which President Lincoln used as justification for his decision. However, many still perceive it as a loophole and a dictatorial tendency, which, whilst constitutional, was unwarranted.

[14] Push-pin is a blatantly uncomplicated game involving each player setting up one needle on a table and then pushing it across their opponent's needle. Many philosophers have referred to it in their ideologies to symbolise a worthless form of entertainment, but J. Bentham still deems it pleasurable, regardless of its simplicity.

[15] The name 'Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals' is hereafter abbreviated as 'GMM' for simplification purposes.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories.

ACT UTILITARIANISM

- Alfange Jr., Dean. (1969). “Jeremy Bentham and the Codification of Law”. Cornell Law Review vol. 55, no. 1: pp. 58–77. Available online.

- Bentham, Jeremy. (1789). Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation § On the Principle of Utility. Reproduced on BCcampus.com. Available online.

- Driver, Julia. (2022). "The History of Utilitarianism" § Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Eggleston, Ben. (2017). "Act utilitarianism". PhilPapers. University of Western Ontario. Canada.

- Miller, Jacques-Alain; Miller, Richard. (1987). “Jeremy Bentham’s Panoptic Device”. October vol. 41: pp. 3–27. Available on JSTOR.

- Plamenatz, John P.; Duignan Brian; et al. "Jeremy Bentham". Encyclopedia Britannica

- "Philosophy 302: Ethics: The Hedonistic Calculus". philosophy.lander.edu . Lander University, South Carolina. United States.

RULE UTILITARIANISM

- Anschutz, Richard Paul. "John Stuart Mill". Encyclopedia Britannica

- Driver, Julia. (2022). "The History of Utilitarianism" § John Stuart Mill. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Mill, John Stuart. (2001). On Liberty. Batoche Books Limited. Ontario, Canada. Available online.

- Mill, John Stuart. (2009). Utilitarianism. The Floating Press. Available online.

- Pontes, Ariel. (December 24, 2020). "Rule utilitarianism: Should we ever break rules for the greater good?". Medium.

- Turner, Edward Raymond. (1913). “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England”. The American Political Science Review vol. 7, no. 4: pp. 588–609. Available on JSTOR.

- "Philosophy 302: Ethics: The Hedonistic Calculus". philosophy.lander.edu. Lander University, South Carolina. United States.

KANT AND DEONTOLOGY

- Alexander, Larry and Moore, Michael. (2021). "Deontological Ethics". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Bird, Otto Allen; Duignan, Brian; et al. (2024). "Immanuel Kant". Encyclopedia Britannica

- Johnson, Robert and Cureton, Adam. (2022). "Kant’s Moral Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. California, United States.

- Kant, Immanuel. (2017). Groundwork for the Metaphysic of Morals. Reproduced on Early Modern Texts.

- "Most Common Criticisms of Utilitarianism (and why they fail)". utilitarian.org.

SUSPENSION OF HABEAS CORPUS

- Dueholm, James A. (2008). “Lincoln's Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus: An Historical and Constitutional Analysis”. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association vol. 29, no. 2: pp. 47–66. Available online.

- McGinty, Brian. (2011). The Body of John Merryman: Abraham Lincoln and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. United States. Available online (preview).

- "Writ of Habeas Corpus and the Suspension Clause". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School.

OTHERS

- Darwin, Charles. (1889). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. D. Appleton and Company. New York City, New York. United States. Reproduced on The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.

- Dickens, Charles. (1905). Hard Times. Chapman and Hall Limited. London, United Kingdom. Reproduced on Project Gutenberg.

GENERAL

- Baron, Peter. (2015). "Handout: Utilitarianism". Philosophical Investigations.

- Cartwright, Mark. (2023). "Social Change in the British Industrial Revolution". World History Encyclopedia.

- Duignan, Brian; West, Henry R.; et al. "Utilitarianism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Haines, William. "Consequentialism" § Basic Issues and Simple Versions. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . University of Hong Kong. China.

- Nathanson, Stephen. "Act and Rule Utilitarianism". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Northeastern University, Massachusetts. United States.

- Pecorino, Philip A. "Chapter 8: Ethics: Utilitarianism". Queensborough Community College. New York, United States

- Veenhoven, Ruut. (2004). “Happiness As an Aim in Public Policy: The greatest happiness principle”. Positive Psychology in Practice § Chapter 39. Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The Netherlands. Available online.

- "Normative ethics". New World Encyclopedia.

- "Social Life in Victorian England". philosophy.lander.edu. University of Delaware, Delaware. United States.

SUGGESTED VIEWING

- Biographics. (April 22, 2019). "Jeremy Bentham - Founder of Modern Utilitarianism". On YouTube.

- CrashCourse. (November 22, 2016). "Utilitarianism: Crash Course Philosophy #36". On YouTube.

- Jeffrey Kaplan. (January 9, 2020). "Utilitarianism". On YouTube.

- Tom Richey. (April 17, 2014). "John Stuart Mill: An Introduction (On Liberty, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women)". On YouTube.

- YaleCourses. (April 5, 2011). "4. Origins of Classical Utilitarianism". On YouTube.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning UTILITARIANISM. The rest can be accessed from my Utilitarianism and Kantianism series.

Y'all ought to take it easy.

nwas blog btw