Punishment Does Not Reduce Crime

Blog by

Last updated: Saturday May 4th, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Saturday May 4th, 2024

Report this blog

+10

Quick Links

This blog briefly examines punitive penal methods' failings and their ineffectiveness in reducing crime rates. Please note that this is just an opinion article; I understand that there are many great arguments in favour of strict punishment in prisons. Nonetheless, in my view, the facts and statistics do not tend to support punitive systems. Moreover, this blog covers general trends observed in penal systems in the Western World and neglects those in the East. It is not laser-focused on any one nation, except for the United Kingdom, as I attempt to generalise as much as possible, perhaps at the expense of glossing over unique individual examples.

Unlike many of my blogs, this one is not particularly technical, or even all that long, and can easily be understood by anyone, which is crucial considering the gravity of its subject. For certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites .

Unlike many of my blogs, this one is not particularly technical, or even all that long, and can easily be understood by anyone, which is crucial considering the gravity of its subject. For certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites .

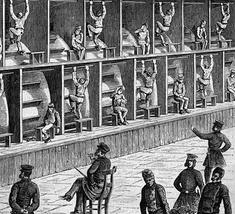

The treadmill at Coldbath Fields Prison in the Victorian-era United Kingdom: a symbol of punitive cruelty in the Victorian era

Abstract

This is a summary of Roy D. King and Rod Morgan's research on the British penal system in the 1980s. The full report can be accessed here:

The vast increase in the number of prisons in the United Kingdom in recent years linked to its abnormally high detainment rate has cast doubts on the British punitive system's efficacy. Between 1979 and 1994, approximately 20,000 places were added, at the expense of billions in taxpayers' money, but to little avail. Due to their overcrowded nature and social changes (i.e., a surge in the crime rate) resulting in more violent/serious offenders being incarcerated, managing prisons has become an onerous task. Whilst only ten per cent of offences in the 1940s were non-violent, this gradually escalated to forty per cent by the 1980s. Consequently, a proliferation of disobedience has been observed in late-twentieth-century prisons. Besides logistical concerns, prisons are not fulfilling their function as almost half of detainees return a few years after being released. These factors have elevated the punitive system to top-priority status in British domestic policy; whilst some dismiss the need for reform, many maintain that the system must be overhauled to serve its purpose effectively. Some argue that imprisonment conditions in the United Kingdom are too oppressive and antiquated, which pose a particular threat to downtrodden minority populations, Another common concern is the system's overly punitive nature which can be made more rehabilitative, in turn remedying many logistical issues and bettering the chance for prisoners to learn from their wrongdoings.

The below are some prisoners' reflections on life in prison:

- 'No one learns anything that will be any help to them when they go out. I'm not aware, for instance, that there's an insatiable demand at good rates of pay for men who can scrub and clean and polish, or make roughly-fitting shoes or brushes, or boil hundredweights of cabbage and potatoes. Really it's beyond me why they don't do things like buying up old motor cars and teaching men the rudiments of being garage mechanics, show them how to rewire a house, repair television sets, or make tables and chairs—anything that's got at least some connection with the sort of job they might get outside'. (Waiter C., aged 54)

- 'All these places do for me is make me determined to hit back harder than ever when I get out. I've a chip on my shoulder, yes, but I don't think I had it so much when I first started being sent to prison'. (Les M., aged 34)

- 'The only sort of way I could tell you about myself, how I am doing this length of time, I suppose it would be to get a cup of water and float a burnt-out match on it and sit and watch it, see how it got water-logged and gradually got lower and lower sinking under the surface, that'd be about it, how it is, that'd be me'. (Len B., aged 45)

Excessive Castigation

The insistence on punishing prisoners and treating them as second-class citizens further fuels their cynical attitude towards authority. Prisons have not aged well throughout the years, still widely perceived as a microcosm of the bygone Victorian era. One cannot deny the cruciality of discipline in making prisoners conscious of the value of ethical behaviour, but a line must be drawn between constructive discipline and debasing discipline. Article Five of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: 'No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment' seems to be repeatedly violated as prisons treat inmates as toy soldiers rather than humans. Every hint of misbehaviour is chastised, every spot of insubordinacy is reprimanded. Every part of their lives and actions is relentlessly monitored, akin to Jeremy Bentham's model of the Panopticon, now viewed as a glimpse into a dystopian world of unhinged mass surveillance.

However, many fail to realise that this dystopian realm exists, taking the form of prisons, and its ramifications on individuals are as grim as envisioned. With such a suffocating atmosphere dominated by authorities resemblant to Oceania in George Orwell's novel 1984, it comes as no surprise that prisoners grow to despise regulations and appropriate modes of conduct, which they perceive as conducive to suffering.

A sketch of the Panopticon: Jeremy Bentham's idea of a perfect prison allowing for a single guard to oversee every inmate without them knowing they are being watched; one of his many hypothetical social reforms, the Panopticon is characterised by a sense of utility in securing absolute discipline; in fact, French philosopher Michel Foucault used Bentham's idea as a metonym for the mass surveillance prevalent in society

Deprivation of Socialisation

Besides authority, punitive excess drives convicts to repulse society. Psychologists and evolutionary biologists repeatedly stress the cruciality of an individual's interaction with members of the same species to its survival. In the case of humans, prolonged periods of seclusion leave an indelible psychological stain on one's outlook on others. Minimal social interaction invariably results in egocentrism and cynicism, as the individual would be unable to fathom the significance of the wider community.

This perfectly fits in with liberated criminals' desire to avenge themselves from society, automatically framing it for their years of unmitigated isolation. Being kept from socialising freely with other inmates or seeing family members for a prolonged time takes a severe toll on their well-being. Such blatantly degrading punishment—contradictory to human nature—is another feeble excuse for depriving convicts of any liberty, which only burdens them with psychological agony.

Cartoon displaying the gravity of solitary confinement in prison: inmates' lack of connection with the outside world renders them mere social outcasts

Lack of Rehabilitation

Dogged declination to adopt modern rehabilitative methods definitively eliminates any possibility for prisoners to rectify their criminal manner effectively. Many politicians fear penal reform, retaining confidence in the tried and tested modes of categorical punishment without treatment. Indeed, these modes are tried, tested, but not proven, and never have been shown to provide convicts with an ample opportunity to start life anew once freed from prison. Opposition to rehabilitation seems wrought by entrenched conservatism, sheer apathy, ineptitude or grave disconnection from reality. Yet, these attitudes remain the doctrines by which prisons operate.

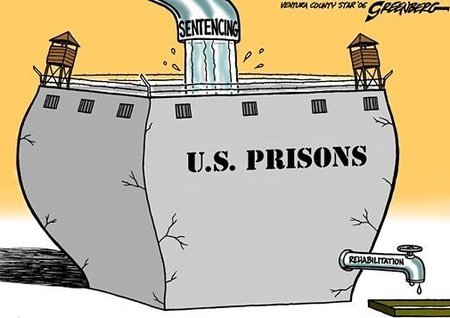

Inmates' years in prison amount to nothing for no useful skill is acquired; access to courses in trade professions, community service or general education is refused. They are deprived of extensive psychological therapy to cure any mental condition they may have that fomented the urge to commit a crime. Norway's incarceration system, granting inmates equal liberties to normal citizens and programs to reintegrate into society is the specimen of rehabilitation's efficacy in reducing crime; the nation's recidivism rate (likeliness to re-offend) sits at twenty per cent—over fifty per cent lower than the United States'.

Cartoon illustrating the overflow in United States prisons due to a lack of investment in rehabilitation: recidivism rates remain high as long as prisoners are not encouraged to recover and seek work opportunities once released

Assessment

Punitive penal systems have proven ineffective at aiding criminals in psychologically recovering, finding success once freed and assimilating into society—a waste of $110 a day in taxpayers' money per prisoner in the United States, for example. Many rigorous policies must be done away with and the door for reforms be opened. Discipline and surveillance need not devolve into austerity and the complete suffocation of inmates' liberties. They must be enabled to interact amicably with each other and the authorities. Most pivotally, therapy, educative courses and work opportunities must be offered. Punishment alone cannot suffice in eliminating crime; rehabilitative reforms must be enacted to foster a change in criminals, treating them as disadvantaged members of society and not as maniacal sociopaths. Prison Insider conclusively notes that in most Western countries such as Malta:

'When prisoners are released, they are simply handed back the clothes they wore the first day they were locked up'.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog.

- Overcrowding

- Employability

- Human rights violations

- Solitary confinement

- Rehabilitation

- United Nations Report

- Howard League Report

However, my progressive perspective on prisons is not the only one... so one should consider consulting some alternative views.

_________________________________________________________________________________

I also think that the whole of society needs to be changed somewhat to deter youngsters from taking up crime in the first place. How we would achieve this is like trying to find the Holy Grail!

Also, this doesn't exactly contradict your point, but American prisons are already very overcrowded, and the US government has been running on deficit spending for the last 20 years or so. While focusing heavily on rehabilitation may work for a smaller and relatively richer population per capita country like Norway, it would be very difficult for the American prison system to spend the amounts of money needed to cover the costs.