The French Revolution - A Complete Guide (Part 2)

Blog by

First published: Monday February 5th, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Monday February 5th, 2024

Report this blog

+5

Quick Links

- Overview

- Proclamation of the Republic

- The National Convention and Rise of the Montagnards

- Robespierre and the Reign of Terror

- Counterrevolution and the White Terror

- The Thermidorian Reaction

- The Directory

- Rise of Napoleon and End of the Revolution

- Napoleon's Domestic Rule

- The Napoleonic Wars

- Descriptive Maps (courtesy of EmperorTigerstar)

- The Concert of Europe

- Liberalism and the 1848 Revolutions

- Nationalism

- Democracy and Political Reform

- Summary

- Further Reading

Overview

This blog – the second of a two-part series – shall delineate the Reign of Terror, Directory, rise of Napoleon, immediate consequences, and impact of the French Revolution. It is chiefly intended for college students and research purposes due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. Nevertheless, anyone interested in history will find comfort or respite in this blog. I wish anyone about to embark on this extensive, and perhaps treacherous, academic journey much success and enjoyment!

Due to this blog's sheer length, I have provided a summary of the main points.

To follow this blog thoroughly, one should consult the first blog in this series, which recounts the events of the Revolution from 1789 to 1791 and the Revolutionary Wars' progress.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Proclamation of the Republic

King Louis XVI repudiated the revolutionary wars; besides the declaration of war, he had vetoed much of the Legislative Assembly’s propositions – such as the sequestration of land from the First and Second Estates – but these were typically overturned. Combined with the Flight to Varennes fiasco, the nation’s outlook on the monarchy had soured into antipathy – seen as obstacles to the revolutionary progress. Consequently, calls for republicanism started resonating with the masses more, such that the Tuileries Palace – the King’s residence – was stormed on 10th August.

Proclamation of the First French Republic on 21st September 1792: following Louis XVI's vetoing of many of the Legislative Assembly's proposals, the monarchy became increasing disdained

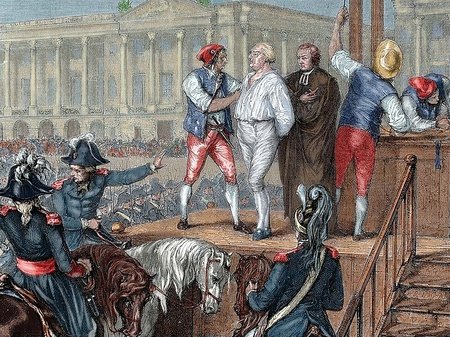

The execution of Louis XVI on 21st January 1793: after the Flight to Varennes, he became considered a traitor

A month later, on 21st September, the monarchy was abolished and the First French Republic was proclaimed. On 21st January 1793, King Louis XVI met his definitive fate by execution, with Robespierre declaring that “the King must die so that France may live”. A day before the founding of the Republic, the Legislative Assembly was replaced with the National Convention, composed of newly elected members from the three established political parties: ‘la Montagne’ (The Mountain), ‘la Gironde’ (Girondins) and ‘la Plaine’ (The Plain). Whilst initially part of the Jacobin Club, having common interests in establishing a constitutional monarchy, political factionalism soon arose.

The National Convention and Rise of the Montagnards

After the first – and only – election of the National Convention in 1792, the Plain gained a slim majority, with the Montagnards and Girondins controlling approximately twenty-five per cent of the seats each. After the September Massacres – the mass murder of Parisian prisoners – French politics became more polarised, with the Montagnards softly advocating violence and extreme government action to enforce the revolutionary ideals, even if such principles had to be contradicted in achieving this. The more moderate Girondins emerged as opponents of such extremism, also favouring privatisation, laissez-faire economics and more lenient action towards the monarchy. The Plain was syncretic and poorly organised, although they typically coalesced with the Montagnards in the Reign of Terror.

The September Massacres: leading to the radicalisation of the French Revolution and political factionalism between the Montagnards and Girondins

Jacques Pierre Brissot - leader of the Girondins - and twenty other Girondins being sentenced to death by the Committee of Public Safety: leading to the decline of the political faction and the dominance of the Montagnards

Due to their monarchist sympathies and refusal to accept the government’s duress and brutality – combined with their unpopularity among the ‘sans-culottes’ – the Girondins’ authority in the National Convention remained tenuous. After the Insurrection of 31 May-2 June involving the removal of several Girondin deputies, they were definitively purged from government, resulting in the consolidation of power under the Montagnards. Thereafter, until mid-1794, politics would be dominated by the Committee of Public Safety – a political body acting as a police force to ‘secure the revolutionary ideals’ – rendering France a dictatorship.

Robespierre and the Reign of Terror

With the economy and war in Europe going poorly under the Girondin government, the Montagnards opportunely purged them from the National Convention and established a dictatorship, centralising authority under the Committee of Public Safety – subdivided into the Revolutionary Tribunal (the criminal tribunal) and a watch committee (the espionage body). Established in April 1793, the Committee of Public Safety became the indelible symbol of the French Revolution’s radicalism due to its near-absolute control over citizens’ lives under Maximilien Robespierre’s leadership.

Whilst initially more temperate under Georges Danton, Robespierre asserted his dominance over the National Convention after the Insurrection of 31 May-2 June, assuming extensive political power to make him a dictator. Robespierre’s prime tactic in maintaining his authority – supposedly to defend revolutionary ideals – was mass paranoia and violence, expressed in the ‘sans-culottes’s’ call to make “terror on the order of the day” (Camille Desmoulins). A slew of inordinate and mostly sanguinary measures to effect his radical ideals followed, encapsulated in the Reign of Terror.

Maximilien Robespierre: leader of the Committee of Public Safety from August 1793 to July 1794 who exercised intense paranoia and brutality during his dictatorial rule

Heads of aristocrats on pikes: deemed 'traitors of the revolution', many upper-class citizens were unjustly executed without a fair trial - a contradiction of the 'Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen'

Robespierre was devoted to “maintain[ing] equality and encourage[ing] virtue”, but his methods of enforcing egalitarianism and liberty were excessive and contradictory to the virtues themselves. Firstly, he involved the government more in the economy – against the previous administrations’ commitment to economic liberalism – by implementing the General Maximum to control food prices, fundamentally causing mass famines throughout the country. Additionally, many churches were shut down and Christianity was essentially abrogated, replaced by the Cult of Reason. A mass emigration of the clergy ensued, compounded by that of the aristocracy, fearing they would be executed under the Law of Suspects.

The Law of Suspects ordered that any purported ‘enemies of the revolution’ – not abiding by revolutionary principles – be tried and executed, culminating in the demise of innocent civilians and political opponents to Robespierre, such as Georges Danton and Marie Antoinette. Extended by the Priarial Law – eliminating the right to a fair trial and prevention from arbitrary arrest – mass paranoia flared, culminating in the execution of approximately 50,000 civilians, many of whom were not guilty and simply deprived of the right to defend themselves, mandated in the Constitution of 1791.

The Law of Suspects ordered that any purported ‘enemies of the revolution’ – not abiding by revolutionary principles – be tried and executed, culminating in the demise of innocent civilians and political opponents to Robespierre, such as Georges Danton and Marie Antoinette. Extended by the Priarial Law – eliminating the right to a fair trial and prevention from arbitrary arrest – mass paranoia flared, culminating in the execution of approximately 50,000 civilians, many of whom were not guilty and simply deprived of the right to defend themselves, mandated in the Constitution of 1791.

Counterrevolution and the White Terror

Due to widespread violence, left-wing extremism and intense anti-clericalism wrought by Robespierre and the Montagnards, many Catholics, monarchists, Girondist sympathisers and rural citizens sought to retaliate against the Reign of Terror. Consequently, a counterrevolution broke out, as seen in the War in the Vendée in Western France. Eventually, the reaction against the Reign of Terror proliferated with fears of a mass purge following the Priarial Law’s passage without the National Convention’s consent. It became evident that the Committee of Public Safety was a dictatorship and practically a repudiation of the promised democratic ideals at the beginning of the revolution.

The War in the Vendée: a military reaction to the anti-monarchist and anti-clerical policies adopted during the Reign of Terror

The Coup of 9 Thermidor: leading to the end of the Reign of Terror and the commencement of the Thermidorian Reaction

With such government overreach, Robespierre became scorned for ruling as a dictator and disregarding the French citizens’ liberties, such that a coup (the Coup of 9 Thermidor) was initiated on 27th July, resulting in the removal of several Montagnard deputies and the execution of Robespierre, leading to the end of the Reign of Terror. After this radical fervour, the Thermidorian Reaction tempered French politics, seeing a return of moderate deputies and a reversal of most of Robespierre’s measures. Nonetheless, hostile action persisted as former Montagnards (more broadly, Jacobins) and associates of the Committee of Public Safety were purged throughout the Thermidorian Reaction – the White Terror.

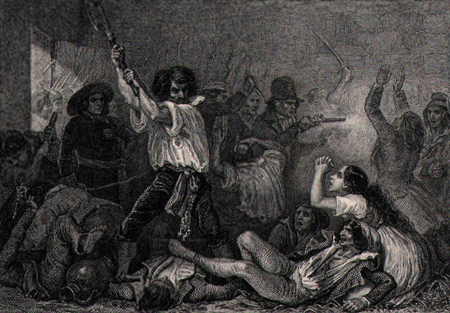

Seeking to avenge the Montagnards, aristocrats, Catholics, Girondins and agrarian workers collectively attempted to exterminate any traces of the Reign of Terror by searching for any sympathisers for the fated dictatorship and assaulting or murdering them. Condoned by the new administration, the White Terror bestrided the Thermidorian Reaction, with many Jacobin prisoners and former leaders being killed haphazardly. Such violence overshadowed the Thermidorian government, appearing as if the Reign of Terror had persisted; after the White Terror, protests dwindled.

The massacre of Jacobin prisoners during the White Terror

_________________________________________________________________________________

The Thermidorian Reaction

After many Montagnards were expelled from government, the National Assembly was reorganised and dominated by members of the Plain, affiliated with the ‘Thermidorian movement’ – opposition to Robespierre and the Mountain’s radical policies. The Committee of Public Safety, Law of Suspects and General Maximum were repealed, although the latter reform bore the undesired consequence of weakening the economy further.

In fact, the economy had not been stable since the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars, with inflation corrupting the currency (the ‘assignat’) and food being overpriced. Additionally, the influence of the aristocratic class in the Thermidorian regime – which had been absent during the Reign of Terror – ensured that the lower and working classes would be financially insecure.

Two dandies (aristocrats) prepared to attack Jacobins: political violence continued during the Thermidorian Reaction due to anti-Montagnardist sentiment

The Coup of 13 Vendémiaire: bringing an end to the Thermidorian Reaction and leading to the Directory's four-year rule

Besides the dire economic situation, many were dismayed at the new administration's endorsement of the White Terror; belligerence in politics became regarded as absolutely unjustifiable and barbarous. The citizens’ discontentment was manifested in the unsuccessful Prairial Uprising in May 1795, demanding a fixed price of bread and the adoption of the Constitution of 1793. Royalists were also unsatisfied with the moderate government and organised a coup to overthrow the National Convention that same year – 13 Vendémiaire. The uprising was quelled, especially by Napoleon, who had acquired a favourable reputation among French citizens. Following these protests, a new constitution would be drafted, establishing a new government.

The Directory

On 22nd August 1795, the Constitution of Year III – a more conservative version of that of 1793 – was approved. It created France’s first bicameral legislature: executive power lay in the hands of a five-member Directory (the ‘Directoire’), and that legislative was distributed between the upper chamber – the Council of Ancients – and the lower chamber – the Council of Five Hundred. Paul Barras – one of the original and most prominent Thermidorians – was elected as one of the five Directors.

The Constitution also admitted many powers to the Directory, such as curbing freedom of the press whilst dividing its authority enough to prevent a repeat of the overbearing Committee of Public Safety. However, this made the legislative process inefficient, rendering the government impotent. Since many royalists and aristocrats were re-elected in the legislative elections of 1795 and 1797, corruption ran rampant and remnants of the ‘Ancien Régime’, such as indirect taxation, were restored.

Paul Barras: the chief leader of the Directory from 1795 to 1799

The aftermath of the Coup of 18 Fructidor: the results of the previous legislative election favouring royalists were overturned and Montagnards were installed into the Council of Five Hundred

Due to this, Jacobins launched a coup in 1797 (Coup of 18 Fructidor), ousting elected monarchists from the legislature and appointing Montagnards in their stead. This insurrection encapsulates the debased state of French politics during the Directory – a return to the prerevolutionary conservative order seemed apparent. However, following the Montagnards’ return to government after the Coup of 18 Fructidor, many royalists, aristocrats and émigrés were unjustly imprisoned or barred from voting.

Worse yet, the economy was extremely weak – inflation remained soaring since the Thermidorian Reaction, and bread became virtually unaffordable, leaving most of France impoverished. Combined with France’s limited success in the Revolutionary Wars, many wanted an efficacious administration to effect the liberal ideals promised a decade prior. The now-beloved general Napoleon was widely regarded as the optimal figure to lead France; this would be actuated in 1799.

Worse yet, the economy was extremely weak – inflation remained soaring since the Thermidorian Reaction, and bread became virtually unaffordable, leaving most of France impoverished. Combined with France’s limited success in the Revolutionary Wars, many wanted an efficacious administration to effect the liberal ideals promised a decade prior. The now-beloved general Napoleon was widely regarded as the optimal figure to lead France; this would be actuated in 1799.

Rise of Napoleon and End of the Revolution

Napoleon’s abrupt rise to power was remarkable – born in Ajaccio, Corsica, on 15th August 1769, nothing about his background denoted a future great leader. His family, whilst linked to the nobility, was middle-class. He moved to mainland France and, in 1785, graduated from a military academy, becoming a second lieutenant in the artillery. As the French Revolution was in full swing, Napoleon aligned himself with the Jacobins and allied with Robespierre.

In 1793, Napoleon was ordered to restore order in Toulon, which had revolted and was being bolstered by Great Britain. This was his first opportunity to exhibit his competence on the battlefield, which he executed victoriously – the British abandoned the city. Two years later, he received national attention following the 13 Vendémaire royalist uprising, leading to his promotion to major general. Following this, Napoleon was given command on the Italian front, leading France to triumph over Austria – earning him legendary status.

'Bonaparte at the Pont d'Arcole': idealising Napoleon's service in the Battle of Arcole - he was instrumental to France's successful Italian Campaign in the War of the First Coalition

The Coup of 18 Brumaire: establishing Napoleon as ruler of France and ending the French Revolution

In 1798, Napoleon spearheaded a campaign to seize Egypt and Syria from the Ottoman Empire, which ultimately failed but further contributed to his favourable reputation. While in Egypt, he learned of in-fighting in the Directory between the two legislative chambers: the Council of Ancient and the Council of Five Hundred. Knowing that citizens would not protest the outcome, he returned to France in 1799, and on 9th November, he launched a coup d’état (the Coup of 18 Brumaire) to take over the Directory.

The next day, the Consulate was established in place of the then government, with Napoleon as First Consul. The Constitution of the Year VIII granted Napoleon dictatorial powers, and for the first time since 1789, did not declare the existence of human rights. This marked the end of the French Revolution – starting with a king and ending with an autocrat. Three years later, he became Consul for Life and, in 1804, crowned himself Emperor of France.

The next day, the Consulate was established in place of the then government, with Napoleon as First Consul. The Constitution of the Year VIII granted Napoleon dictatorial powers, and for the first time since 1789, did not declare the existence of human rights. This marked the end of the French Revolution – starting with a king and ending with an autocrat. Three years later, he became Consul for Life and, in 1804, crowned himself Emperor of France.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Napoleon's Domestic Rule

Napoleon oversaw colossal domestic reforms throughout his sovereignty, many of which were prompted by the French Revolution’s liberal ideals. In January, he established France’s first prolonged central bank – the ‘Banque de France’ (the ‘Banque Générale – founded in 1716 – was France’s first central bank, but was quickly dissolved in 1720 following the Mississippi Bubble). After a decade of economic downturn, high inflation and unaffordable food prices, this stimulated economic recovery.

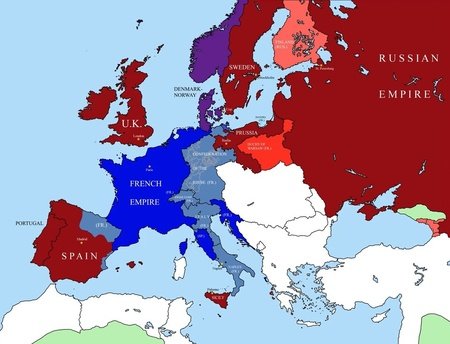

That same year, the Battle of Marengo during the War of the Second Coalition determinately defeated the Austrian army, solidifying the citizens’ and administration’s trust in Napoleon, practically empowering him to consolidate political authority under him and conduct extensive – usually authoritarian – reforms ad hoc. Following a decade of secularism and curtailing the Church’s potency, Napoleon recuperated state relations with the Roman Catholic Church with the issue of the Concordat of 1801.

The signing of the Concordat of 1801: repairing state relations with the Catholic Church and the Papacy

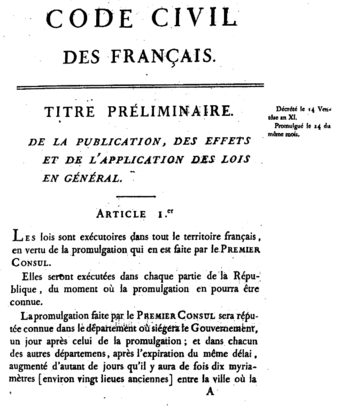

Title page of an early copy of the Napoleonic Code: the first proper French legal code influencing the legal system of over 120 modern countries

Arguably the magnum opus of his domestic transformations was chartering the Napoleonic Code (1804) – standardising laws throughout France, acknowledging the principles of civil liberty (not fully applicable to women), family duties and processes, and property management. These legal principles were disseminated throughout the Empire.

Furthermore, Napoleon overhauled the education system by instituting the University of France and restructuring primary and secondary schools. On the foreign front – being his most significant contribution to world history – Napoleon established the First French Empire dominating continental Europe, propagating nationalistic and liberal ideals and stimulating the creation of new nations.

Furthermore, Napoleon overhauled the education system by instituting the University of France and restructuring primary and secondary schools. On the foreign front – being his most significant contribution to world history – Napoleon established the First French Empire dominating continental Europe, propagating nationalistic and liberal ideals and stimulating the creation of new nations.

The Napoleonic Wars

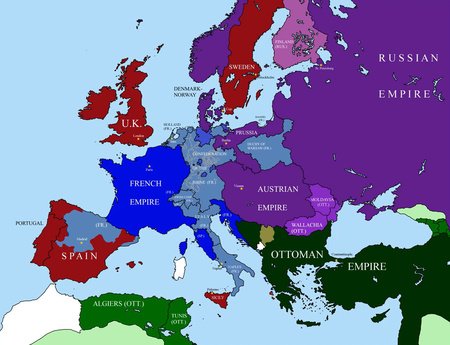

Following the Battle of Marengo (1800) – the last notable engagement in the War of the Second Coalition – the French Revolutionary Wars drove to a conclusion, and Napoleon arranged to expand his empire into central Europe, attempting to dominate Prussia and the Holy Roman Empire, Austria, and later, Russia. These engagements – lasting from 1803 to 1815 – are the Napoleonic Wars, commencing with the formation of the Third Coalition.

He had prepared for this: financially – selling Louisiana to the United States – and militarily – organising the Grande Armée into the corps system (still used nowadays). The Continental System (1806) restricting trade from the United Kingdom to continental Europe and vice versa was another tactic implemented but would prove less successful since an embargo on British goods exacerbated the French cost of living.

Napoleon authorising the Louisiana Purchase: funding his European campaigns and doubling the then United States' size

The Battle of Wagram: concluding the War of the Fifth Coalition

From the War of the Third Coalition to that of the Fifth Coalition, the Napoleonic Wars leaned heavily in France’s favour; by 1809, the French Empire was either allied with or controlled most of continental Europe. Arguably Napoleon’s most consummate military victory was at the Battle of Austerlitz against Austria and Russia in December 1805, bringing the War of the Third Coalition to an end with the Treaty of Pressburg.

He defeated Prussia at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt during the War of the Fourth Coalition in October 1806, and later Russia at the Battle of Friedland in June 1807. Napoleon then imposed the Treaty of Tilsit on Russia, terminating the war. The War of the Fifth Coalition (1809) also resulted in a French victory over Austria, but France’s military and economic resources were being exhausted by the Peninsular War with Spain (1808-14) and the Continental System. Still, Napoleon’s success in the Battle of Wagram (1809) against Austria led to the Treaty of Vienna, mostly leaving French dominance over continental Europe uncontested.

He defeated Prussia at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt during the War of the Fourth Coalition in October 1806, and later Russia at the Battle of Friedland in June 1807. Napoleon then imposed the Treaty of Tilsit on Russia, terminating the war. The War of the Fifth Coalition (1809) also resulted in a French victory over Austria, but France’s military and economic resources were being exhausted by the Peninsular War with Spain (1808-14) and the Continental System. Still, Napoleon’s success in the Battle of Wagram (1809) against Austria led to the Treaty of Vienna, mostly leaving French dominance over continental Europe uncontested.

Until 1812, he consolidated his continental empire, but his alliances with other nations remained tenuous, especially that with Russia. To enforce the Treaty of Tilsit, Napoleon led an army of approximately 650,000 troops into Russia that June but was forced to retreat from Moscow due to harsh weather conditions and Tsar Alexander I’s scorched earth tactic. With his army’s strength diminished, the Sixth Coalition – formed in March 1813 – countered the retreating Grande Armée and at the Battle of Leipzig (1813), Napoleon lost all possessions and alliances east of the Rhine River.

Napoleon's retreat from Russia in 1812: his failed invasion of the country directly led to his Empire's downfall

Napoleon exiled in Saint Helena: his failed attempt to rebuild the Empire culminated in his fate

After the Allies advanced and captured Paris, the Treaty of Fontainebleau enacted on 13th April 1814 forced him to abdicate and exiled him to Elba. The Charter of 1814 restored the Bourbon monarchy – with Louis XVIII as King of France – and established a bicameral parliamentary system. Hoping to rekindle France’s glory as a continental empire, Napoleon returned to France in March 1815 and embarked on another European conquest – the Hundred Days. The Seventh Coalition conclusively defeated him at the Battle of Waterloo; the First French Empire was permanently dissolved, and Napoleon was exiled to Saint Helena, where he died in 1821.

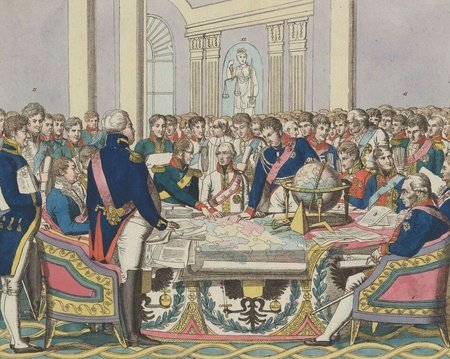

The Second Treaty of Paris signed in November 1815 subjected France to a temporary occupation by the Great Powers, ordered the nation to pay an indemnity of 700 million francs and reversed France's conquest in the Revolutionary Wars, designating the borders it had as of January 1790. Moreover, the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) redrew Europe's national borders following the Napoleonic Wars and established the Congress System, known as 'The Concert of Europe'. The five superpowers dominating the system: the United Kingdom, France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia, would agree – although rarely unanimously – to forestall future events similar to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars by repressing liberalistic and nationalist ideas, and potential revolutions and conflicts.

This was the final fate of twenty-five years of advances aimed at populism, constitutionalism and nationalism, and regnant French dominance in the continent – an annulment of the French revolution and Napoleon’s progress. Yet, the Concert of Europe could not prevent the revolutionary ideals of ‘‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ from proliferating throughout the continent, such that the rest of the century would be characterised by independence movements and widespread revolutions.

This was the final fate of twenty-five years of advances aimed at populism, constitutionalism and nationalism, and regnant French dominance in the continent – an annulment of the French revolution and Napoleon’s progress. Yet, the Concert of Europe could not prevent the revolutionary ideals of ‘‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ from proliferating throughout the continent, such that the rest of the century would be characterised by independence movements and widespread revolutions.

The Congress of Vienna, establishing the Congress System: the immediate outcome of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Era

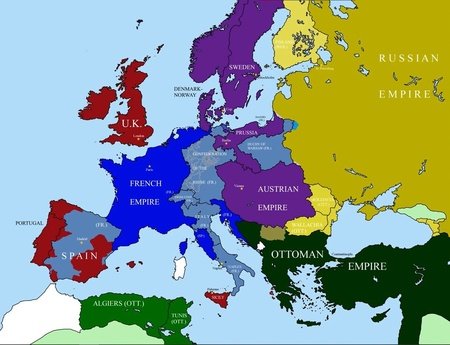

Descriptive Maps (courtesy of EmperorTigerstar)

18th May 1803: the beginning of the War of the Third Coalition, although Austria and Russia would only join the Coalition two years later

6th October 1806: the beginning of the War of the Fourth Coalition - the Confederation of the Rhine had been formed and Naples had become a French puppet state

9th July 1807: the signing of the Treaty of Tilsit ending the War of the Fourth Coalition - Prussia and Russia became French allies, and Russia was at war with the Ottoman Empire

14th October 1809: the Treaty of Schönbrunn ends the War of the Fifth Coalition - Austria also becomes allied with France, the Peninsular War with Spain had commenced

24th June 1812: Napoleon invades Russia, the Trafalgar War continues to limit France militarily, other nations prepare to form the Sixth Coalition

3rd March 1813: the War of the Sixth Coalition commences - Napoleon's invasion of Russia had failed, the Trafalgar War was turning in Spain's favour

11th April 1814: the Treaty of Fontainebleau leads to the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition - the major powers prepare to redraw the borders of Europe

8th July 1815: Napoleon's Hundred Days campaign ends - the Napoleonic Wars are concluded and the First French Empire ends with the Second Bourbon Restoration

_________________________________________________________________________________

The Concert of Europe

The Napoleonic Wars instigated the Concert of Europe – The Concert of Europe was a series of diplomatic conferences hosted by the Congress System – the mutual agreement between the five European great powers of the time: the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Austria, and Prussia – throughout the nineteenth century intended to ensure political stability in the continent by negotiating peace or forcing a cessation to uprisings, conflicts and war in European nations.

Although rarely unanimously, the powers sought to secure concord to avert a repeat of the Napoleonic Wars through two chief tactics: balance of power between countries and suppressing liberalism and nationalism. Whilst weakened by the emergence of some wars – such as the Crimean and Franco-German Wars – the Concert of Europe often resolved nineteenth-century conflicts, as seen with the London Conference (1830) granting Belgium independence, the Congress of Paris (1856) determining the peace terms for the Crimean War, and the Congress of Berlin (1878) tackling the Eastern Question.

The Congress of Paris (1856): one of the most crucial conferences of the Concert of Europe

Liberalism and the 1848 Revolutions

The French Revolution’s primary accomplishment – promulgating and mandating liberal principles to safeguard every citizen’s rights – was gradually realised throughout time. Shortly after the National Constituent Assembly’s formation, the August Decrees – issued in August 1789 – rescinded the feudal system and any privileges previously borne by the First and Second Estates and strictures on the Third Estate, meaning that no formal financial or social distinctions between social classes could be made.

They preceded the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – a keystone document of the Enlightenment liberal ideals, guaranteeing “liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression” to every ‘man’ (Article II) – deemed equal and free agents. For instance, the rights to private property, free speech, freedom of the press, prevention from arbitrary arrest and equality before the law were granted.

Cartoon displaying the night of 4th August 1789, in which feudalism was abolished: financial and social privileges were rescinded

The 1848 Revolution of France: the cause for liberalism and democracy was furthered and eventually materialised with the establishment of the Second French Republic

Whilst mandated in the Constitution of 1791, these liberal ideals would not be enforced due to the autocratic regimes of Maximilien Robespierre, Napoleon I, Louis XVIII, Charles X, and finally, Louis Philippe. The Orléanist regime led by Louis Philippe – only latently populist – was overthrown in the French Revolution of 1848, with citizens demanding workers’ rights, price stability, and, above all, a democratic government.

In fact, the 1848 Revolutions spread throughout Europe, with the prevalent aims being an acknowledgement of popular sovereignty, nationalism, constitutionalism, and socialism (more broadly, protection of workers) – ideas emanating from the French Revolution of 1789. Although the Springtime of the Peoples failed, the French Revolution of 1848 partially succeeded, with the first presidential election with universal male suffrage held that year, as well as slavery being abolished.

In fact, the 1848 Revolutions spread throughout Europe, with the prevalent aims being an acknowledgement of popular sovereignty, nationalism, constitutionalism, and socialism (more broadly, protection of workers) – ideas emanating from the French Revolution of 1789. Although the Springtime of the Peoples failed, the French Revolution of 1848 partially succeeded, with the first presidential election with universal male suffrage held that year, as well as slavery being abolished.

Although delayed by Napoleon III’s dictatorial rule from 1851 to 1870, the Third and Fourth Republics would enact significant reforms to materialise the liberalism envisioned by the French Revolution (1789). For instance, egalitarianism was acknowledged; women gained suffrage in 1945, and the principle of gender equality was introduced in the 1946 Constitution. That same constitution would grant every citizen equal citizen “with no distinction as to race”; the most considerable prior reform in racial equality was the abolition of slavery in 1848. Furthermore, the strict separation of church and state (secularism) was mandated in 1905, and freedom of the press was fully granted with the passage of the Press Law of 1881.

Facsimile of the Constitution of 1946: granting many liberties originally envisioned in the French Revolution

Nationalism

Nationalism – the collectivist movement uniting people of a particular culture (especially language) under one nation and synchronising government function with bolstering the nation – arose from the French Revolution and morphed nineteenth-century European history. As delineated in Article III of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – “The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation”, the ‘nation’ refers to the country’s citizens (in this case, France), which the government was to be responsible for safeguarding. Disseminating through the Napoleonic Wars – such as with the agglomeration of most German states within the Holy Roman Empire into one (Confederation of the Rhine) – European folk sought to form new nations based on a common identity, ethnicity, language or religion.

Princes from the former German states comprising the Holy Roman Empire affirming their loyalty to the Confederation of the Rhine: dissolving the Holy Roman Empire and conglomerating its constituents into one nation

The Battle of Karpenisi (1823) during the Greek War of Independence: a nationalist movement directly inspired by the French Revolution

1821 saw the first display of nationalistic sentiment, as Greeks revolted against the Ottoman Empire and fully gained independence in 1830. Greece’s success in pursuing nationalism encouraged ethnic Germans to demand the creation of a united Germany (same for Italians), and ethnic Austrians, Hungarians, Croats, Slovenes, et cetera to splinter from the Austrian Empire.

Eventually, Italian and German Unification occurred in 1871, and Austria-Hungary was dissolved in 1919, fostering the creation of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the Great Eastern Crisis – a series of Balkan uprisings within the Ottoman Empire – stimulated the independence of Romania (1877), Bulgaria (1878, partially) Serbia (1878, fully), and later other nations during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. These independence movements stemmed from the proliferation of nationalism during the French Revolution.

Eventually, Italian and German Unification occurred in 1871, and Austria-Hungary was dissolved in 1919, fostering the creation of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the Great Eastern Crisis – a series of Balkan uprisings within the Ottoman Empire – stimulated the independence of Romania (1877), Bulgaria (1878, partially) Serbia (1878, fully), and later other nations during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. These independence movements stemmed from the proliferation of nationalism during the French Revolution.

Democracy and Political Reform

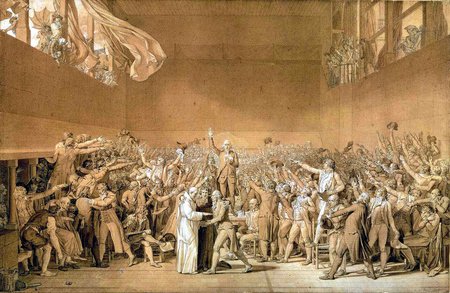

The concept of a democratic government committed to the people’s exigencies – supposedly ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’ (Abraham Lincoln) – and expunging authoritarianism and special favours materialised in the 1870s. Following the Tennis Court Oath on 20th June 1789, the National Assembly usurped many of the King’s powers and became the French governing body. Most representatives were bourgeoisie members (hence, the Third Estate), reflecting the population of the country, 98% comprised the Third Estate; Abbé Sieyes considered them to be ‘nothing in the political order’, desiring to ‘become something’ (‘Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État’). In representing their interests, the Assembly became the first democratic government in Europe.

The Tennis Court Oath establishing the National Assembly as France's effective governing body: composed mostly of Third Estate members, it was one of Europe's first democratic administrations

Adolphe Thiers: the second president of France, and the first of the Third French Republic

Popular sovereignty became predominant, such that the monarchy, seen as despotic, was abolished on 21st September 1792. The Constitution of Year III, establishing the Directory in 1795, also implemented many checks and balances and division of powers, mindful of eliminating any potential autocracy. Due to the dictatorial regimes in the Napoleonic Era and following the Bourbon Restoration, it would take until 1848 for their first direct election for a leader with universal male suffrage; free presidential elections (which were ‘indirect’ until 1965) were held from 1873.

The Revolution also encouraged other European peoples to protest their absolute monarchies, replaced with democracy. France would not abandon autocracy until 1870 – when Emperor Napoleon III was deposed following its poor performance in the Franco-German War, and the Third Republic was proclaimed – with Adolphe Thiers as its first ‘true’ president.

The Revolution also encouraged other European peoples to protest their absolute monarchies, replaced with democracy. France would not abandon autocracy until 1870 – when Emperor Napoleon III was deposed following its poor performance in the Franco-German War, and the Third Republic was proclaimed – with Adolphe Thiers as its first ‘true’ president.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Summary

REPUBLICAN AND THE TERROR

- Louis XVI's refusal to cooperate with the Legislative Assembly led to the Storming of the Tuileries Palace and later the abolition of the monarchy; the First French Republic was proclaimed on 21st September 1792

- The National Convention was established a day prior, leading to the dominance of three political factions: the left-wing Montagnards (more broadly, the Jacobins), the centrist to centre-right Girondins, and the syncretic Plain

- After the September Massacres, the divide between the Montagnards and the Girondins grew; since the latter refused to assent to the centralisation of power and with federal action to support Parisians economically, they were purged from the National Convention

- This allowed the Montagnards to consolidate all political power under the Committee of Public Safety, led by Maximilien Robespierre from July 1793 to June 1794

- The emergent Reign of Terror resulted in mass violence and paranoia, the curtailment of civil liberties, the disintegration of the judicial system, and the mass purge of clergymen and aristocrats

- Due to the violence, left-wing extremism and intense anti-clericalism, a counterrevolution to Robespierre's dictatorship was initiated, as seen in the War in the Vendée

- The Priarial Law's passage without the National Convention's consent evinced Robespierre's tyranny, such that the Coup of 9 Thermidor was launched, removing several Montagnards from government and leading to Robespierre's execution

- Whilst the Reign of Terror ended, violence persisted due to the White Terror – the purging of former Montagnards, associates of the Committee of Public Safety and sympathisers of Robespierre

REACTION AND END OF THE REVOLUTION

- French politics then shifted towards centrism, as many deputies opposing the Reign of Terror now occupied the National Convention – the Thermidorian Reaction

- However, the Thermidorian government was short-lived due to its seeming endorsement of the White Terror and the dire economic situation wrought by the repeal of the General Maximum and its more laissez-faire approach

- Hence, the Constitution of Year III was approved, creating the bicameral Directory to replace the National Convention in November 1795

- Owing to its legislative inefficiency, widespread corruption, economic mismanagement and aristocratic sympathies, it was unpopular among French citizens

- The Coup of 18 Fructidor in 1797 (illegally) installed many Montagnards into the administration, but political and economic turmoil persisted

- Hence, Napoleon Bonaparte – a then beloved general due to his role in quelling the 13 Vendémaire uprising and his success in the Italian Campaign against Austria (1796-97) – overthrew the Directory following the Coup of 18 Brumaire

- The Constitution of Year VIII (1800) was later mandated, giving him dictatorial abilities in ruling over France as First Consul (later First Consul for Life, and then Emperor)

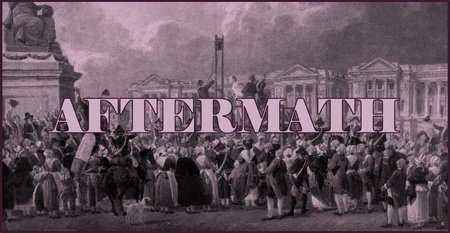

AFTERMATH

- Napoleon achieved many domestic reforms for France: overseeing economic recovery by establishing the central Bank of France in 1800, recuperating state relations with the Roman Catholic Church with the issuing of the Concordat of 1801, reforming the legal system by chartering the Napoleonic Code (1804), overhauled the education system by instituting the University of France and restructuring primary and secondary schools, and most prominently, establishing the First French Empire

- He desired to extend the Empire's influence throughout Europe's entirety, motivating him to embark on a series of conflicts called the 'Napoleonic Wars' (1803-15)

- From the War of the Third Coalition to that of the Fifth Coalition, the Napoleonic Wars leaned heavily in France’s favour; by 1809, the French Empire was either allied with or controlled most of continental Europe

- However, following the Peninsular War (1810-14) and Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia (1812), the Sixth Coalition dissolved the French Empire; the Seventh Coalition countering the Hundred Days Campaign (1815) definitively did so

- The Congress of Vienna (1814-15) redrew Europe's borders after the Napoleonic Wars and established the Congress System, known as 'The Concert of Europe'

- Besides leading to the modernisation of European borders and disseminating the French Revolution's liberal, republican, nationalist and constitutionalist principles, the Napoleonic Wars contributed to the United States' expansion with the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the corps system for organising military units, and progress in the United Kingdom's industrialisation due to the Continental System

LEGACY

- The Napoleonic Wars led the European powers to jointly agree to forestall the potential of such conflict by suppressing revolts and securing the balance of power – the Concert of Europe

- The French Revolution's liberal ideas lingered throughout the public conscience, such that French citizens – and the rest of Europe – would revolt again in 1848 demanding more rights; eventually, universal suffrage was mandated, egalitarianism and secularism were achieved and constitutional liberties became enforced more rigorously

- The Revolution's nationalist notions spread throughout Europe, inspiring many independence and unification movements throughout the nineteenth century, such as the Greek Revolution, German and Italian Unification, and uprisings within the Ottoman Empire – including Ottoman-Persian War (1821-23), the Bosnian Uprising (1831-32) and Albanian Revolts (1833-39)

- After the 1848 Revolutions (especially after the proclamation of the Third French Republic), democracy flourished, with free elections held and the presidency established

_________________________________________________________________________________

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed chronologically in order of use.

REPUBLICANISM AND THE TERROR

REACTION AND END OF THE REVOLUTION

AFTERMATH

LEGACY

MISCELLANEOUS

_________________________________________________________________________________

Curious to know where to find blog lengths cos I'd love that kinda metrics

I am not sure whether there is a way to find blog lengths, they can only be seen when editing a blog.

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢸⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⡇⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢸⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⡿⠿⠟⠛⢉⣉⡀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠘⠛⠋⣉⣁⣤⣤⣶⣾⣿⣿⣿⡇⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢰⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⠿⠿⠛⠋⠉⠁⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠘⠛⠉⠉⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢀⣀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢸⣿⣿⣿⡿⠛⠉⠛⢿⣿⣿⣿⡇⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢈⣉⣉⣉⡁⠀⠀⠀⢈⣉⣉⣉⡁⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⢸⣿⡇⢸⣿⣿⣿⣷⣤⣤⣴⣿⣿⣿⣿⡇⢸⣿⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀