The French Revolution - A Complete Guide (Part 1)

Last updated: Wednesday February 28th, 2024

Report this blog

- Overview

- Factors Leading to the French Revolution

- Overview of the National Assembly

- The Estates System and Estates-General of 1789

- The Tennis Court Oath

- Increased Protest

- The August Decrees

- The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

- Further Constitutional Development

- The Émigrés and the Flight to Varennes

- Beginning of the Revolutionary Wars

- Progress and End to the Wars

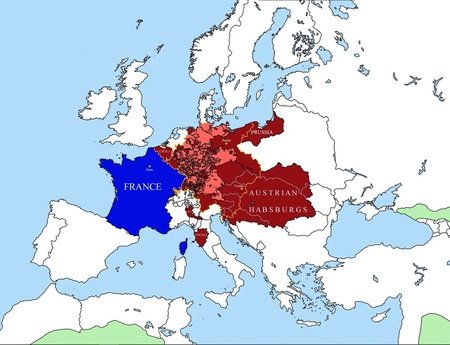

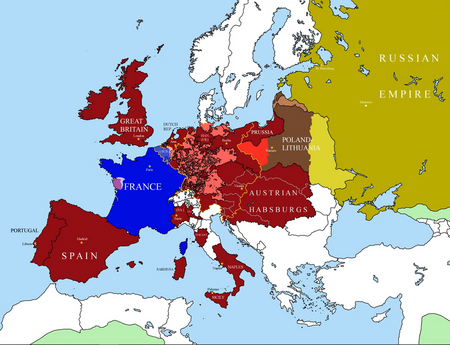

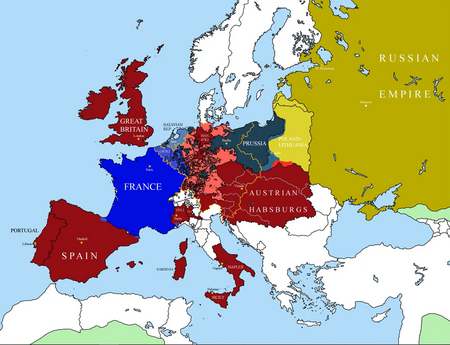

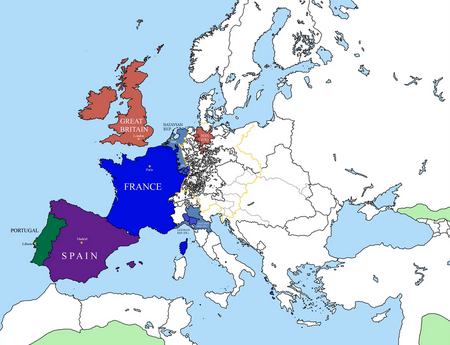

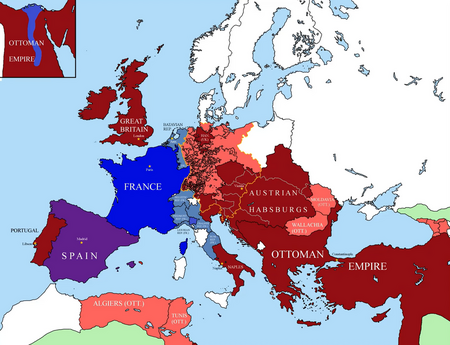

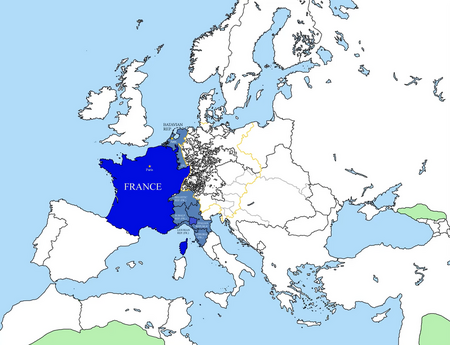

- Descriptive Maps (courtesy of EmperorTigerstar)

- Summary

- Notes

- Further Reading

Overview

This blog – the first of a two-part series – shall delineate the causes and sequence of events of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1791, and provide an overview of the French Revolutionary Wars. It is chiefly intended for college students and research purposes due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. Nevertheless, anyone interested in history will find comfort or respite in this blog. I wish anyone about to embark on this extensive, and perhaps treacherous, academic journey much success and enjoyment!

This blog's sequel can be accessed here.

Due to this blog's sheer length, I have provided a summary of the main points.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

_________________________________________________________________________________

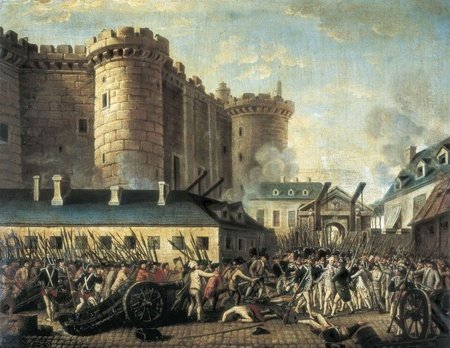

Factors Leading to the French Revolution

The combination of economic, political and social trends in France throughout the eighteenth century favouring nationalism and left-wing politics, along with crop failures, administrative stubbornness and the American Revolution expedited the French Revolution. On the fourteenth of July 1789, the Storming of the Bastille wrought by the people’s dissatisfaction led France down a decade of revolt and tremored the European continent. The extended suffocation of the citizens’ liberties – existing ever since the estates system and absolute regimes – had ensured their discontent. It represented the first public disapproval of the old conservative order, and an embrace of liberal ideals.

Moreover, the dissolution of the central bank in 1720 due to the Mississippi Bubble meant that government spending could not be monitored efficiently. Besides the avalanche of worsening economic issues throughout the century, France’s crop failures in the winter of 1788 led to an acuminate increase in the price of bread. This rendered the cost of living unaffordable for the copious destitute families.

Whilst only these social groups had any political influence, all power was ultimately centralised in the monarch, who had absolute control over the three branches of government: judicial, legislative and executive. Louis XVI was a weak king, as he left the governance of France to his ministers – a system marred by bureaucracy and special interests. Furthermore, as members of the Third Estate began to disapprove of the social inequality and their lack of political representation more vocally, he obstinately refused any change. Ultimately, the public outrage following Louis XVI’s dismissal of Finance Minister Jacques Necker – a constitutional monarchist and advocate for taxation reform – emblematised the need to reconstruct the rigid political system.

Additionally, the First Industrial Revolution [6] organised workers into large groups striving for a common task – empowering a sense of solidarity. Abroad, the success of the American Revolution in overthrowing George III as sovereign of the Thirteen Colonies encouraged Frenchmen to utilise these philosophical concepts in achieving their aims of improved political representation.

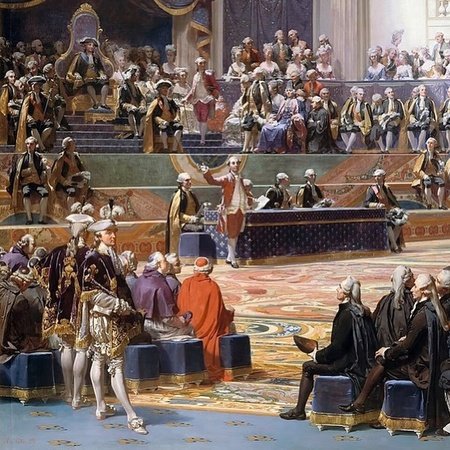

Overview of the National Assembly

The National Assembly (‘Assemblée Nationale’) was the de facto French governing body for a month in mid-1789 possessing the then-powers allocated to the monarch, until it was replaced by the analogous National Constituent Assembly (serving until September 1791) [7]. Although the de jure sovereign, Louis XVI’s authority had been curbed owing to widespread disapproval of the estates system, with the Third Estate – 98% of the population – being patently underrepresented. Hence, following the failed Estates-General of 1789, bourgeoisie representatives took the Tennis Court Oath – admitting most of the King’s political authority and centralising it under a parliament of predominantly Third Estate members, along with some nobles and clergymen [8].

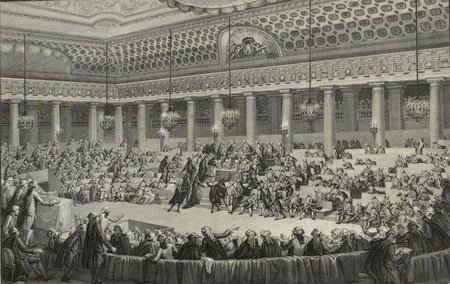

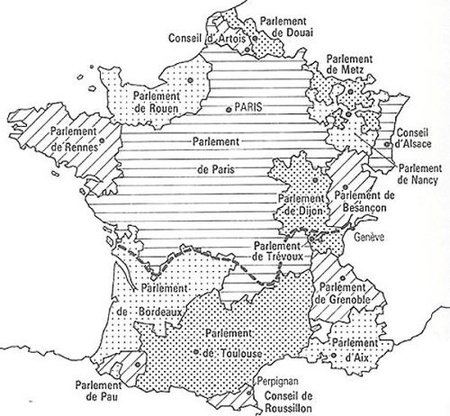

The Estates System and Estates-General of 1789

The Estates-General of 1789 laid the groundwork for the National Assembly’s founding, intensifying citizens’ revulsion at the rampant political inequality. The Estates System divided French society into three classes: the clergy in the First Estate (<0.5% of the population), nobles in the Second (<2%), and everyone else – bourgeoisie, merchants, factory workers, and farmers – in the Third (~98%).

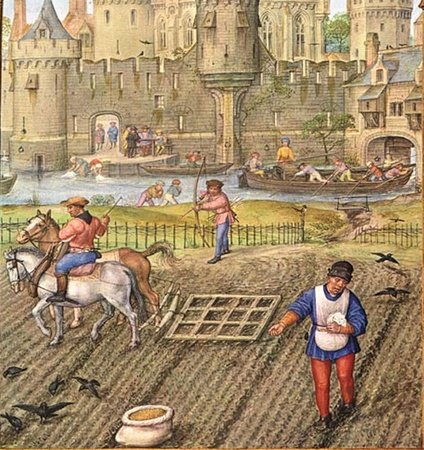

Adapted from the feudal system of social hierarchy and serfdom of the Middle Ages, the upper classes (First and Second Estates) were socially elevated, having several political and financial privileges, whilst lower class members (Third Estate) were subjected to a seigneur, landlord or factory owner and unable to enjoy financial security or political representation. Middle-class citizens (the bourgeoisie) also comprised the Third Estate – lacking personal freedoms – but had access to education and were not deemed serfs.

Due to pervasive restrictions, merchants and artisan workers could not affiliate themselves with a guild to better their working conditions [10] – inhibiting them from demanding wage increases. Additionally, the Church collected a portion of taxation (eight per cent) as tithes – due to the Divine Right tenet, the monarch desired healthy ecclesiastical relations.

The domination of spoils extended outside of government, as many nobles and clergymen asked for special favours from the King, such as a plot of land or public office in exchange for a considerable sum of money – the Third Estate could not seek these. It would only take a nationwide revolution threatening his very reign to kindle his interest in ameliorating their financial and political status, but Louis XVI remained obdurately reluctant to enact any significant reform.

Nevertheless, the process was hardly democratic, as only taxpayers could elect officials, and votes were counted by estate, not per capita. Due to the nobles’ and most of the clergy’s disinclination to approve reform, the Third Estate representatives and some village abbots from the First Estate proclaimed themselves independent from the Estates-General, organising themselves into a 'National Assembly' on 17th June 1789. Three days later, they swore not to disband until the King chartered a constitution enshrining political and economic liberties for lower-class citizens.

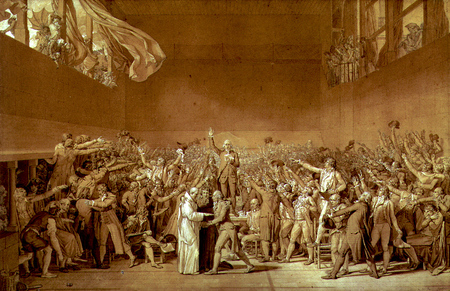

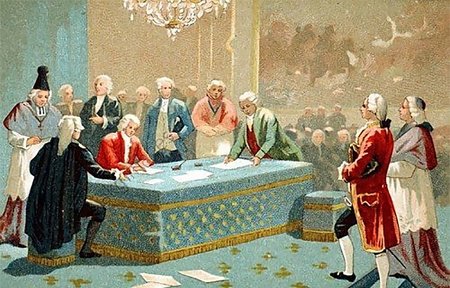

The Tennis Court Oath

The Tennis Court Oath (‘le Serment du Jeu de Paume’) taken on 20th June 1789 by deputies of the Third Estate established the National Assembly as the effective governing body of France. This bestowed them illegal [12] powers such as collecting taxation, overseeing finances and refusing orders from the King. Following a thousand years of absolute rule in France, the National Assembly was the first French representative government, signalling the political transition to constitutionalism. It also served to check the monarch’s previously insurmountable authority and strengthen the representation of the Third Estate. Moreover, the ascendancy of the Assembly signified the cruciality of a constitution to mandate the fundamental liberties of French citizens.

"What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been hitherto in the political order? Nothing. What does it desire to be? To become something." - Abbé Sieyes, ‘Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État’ ('What is the Third Estate')

Whilst some impoverished clergymen and liberal nobles joined the National Assembly, most of the representatives were members of the bourgeoisie (hence, the Third Estate), reflecting the population of the country, 98% of which comprised Third Estate citizens. Such was the overwhelming proportion of lower and middle-class people in the country that Abbé Sieyes in his pamphlet ‘Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État’ considered the Third Estate to be ‘everything’, yet ‘nothing in the political order’. In representing their interests, the Assembly proclaimed itself to be ‘National’.

Increased Protest

The rise of the National Assembly as an illegal ‘democratic’ government dominated by Third Estate members – gradually receding the ‘ancien régime’ [14] – was perceived as a triumph of the revolution for the lower and middle classes over the politically privileged clergy and nobility. Hence, after the Tennis Court Oath, social upheaval in Paris prevailed, whereby Parisians raided the homes of monasteries and aristocrats to source food and ammunition and protested relentlessly. To further the cause of self-autonomy against the King, the city set up its own ruling body (the Paris Commune) on 11th July [15]. The Storming of the Bastille on 14th July sparked national protest and civil disobedience to the rule of law, cementing the National Assembly’s (then renamed to the ‘National Constituent Assembly’) authority as the de facto governing body of France.

The August Decrees

Arguably the National Constituent Assembly’s most notable contribution was its progress towards constitutional development. Amid widespread violence and civil disobedience, with nobles’ property being looted, taxes not being paid and mutinies from the National Guard – culminating in the Women’s March to Versailles and the establishment of the Paris Commune – the cries for mandated individual liberties and social and political equality resonated intensely. Consequentially, the August Decrees were issued in August 1789, rescinding the feudal system, and thereby, any privileges previously borne by the First and Second Estates and strictures on the Third Estate.

"All particular privileges given to certain provinces, district, cities, cantons and communes, financial or otherwise, were abolished because under the new rules, every part of France was equal." - The August Decrees (Article X)

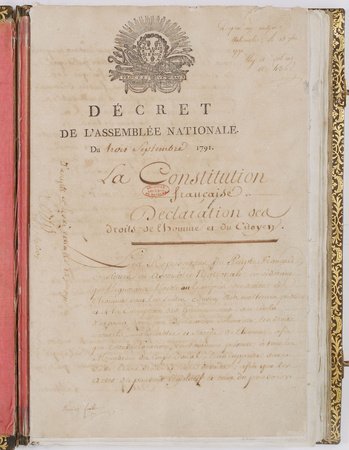

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

More paramountly, the August Decrees preceded the 'Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen' (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen) – one of the first European declarations of rights [18] and the precursor to the first French constitution – the Constitution of 1791. Initially drafted by the Marquis de Lafayette and later by Abbé Sieyes, it is a keystone document of the Enlightenment liberal ideals, guaranteeing “liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression” to every ‘man’ (Article II).

The first article proclaims the corollary that “men are born free and equal in rights” – inspired by John Locke’s 'natural rights' theory [19], positing the inalienability of certain liberties that the state should actively enforce above all else. Such liberties – partially sourced from the United States Constitution and the philosophes’ ideals of a ‘social contract’ [20], separation of powers [21], checks and balances [22] and secularism – were listed in seventeen articles.

"Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others" - 'Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen' (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen)

For instance, the right to private property was granted, stimulating economic liberalism [23] and private enterprise to replace feudalism. One could also hold and communicate their own political opinions and other ideas without being persecuted. Judicial and legal reform – signally, the principles of ‘equality of the law’ and prevention from arbitrary arrest – provided citizens more security, shielding them from the monarch’s auspices in determining the law at his will – “It is legal because I wish it” (Louis XIV).

"L'État, c'est moi" ("I am the state") - attributed to King Louis XIV

Further Constitutional Development

The Constitution of 1791 – the first French constitution – mandated the freedoms conceived by the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’. Since Louis XVI rejected the latter, as did the Jacobin Club for not being egalitarian [26] enough, a new constitution was drafted. Whilst very similar to the Declaration of Rights, it acutely distinguished between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ citizens; the former category comprised males aged over twenty-five who paid taxes equivalent to three days of labour (less than fifteen per cent of the population). Only these were bestowed political rights – those to vote and participate in local and national politics – ‘passive’ citizens were exempt.

Additionally, provincial authority was centralised into a few administrative units to further the actuation of nationalism. Summarily, the Constitution of 1791 established France as a constitutional monarchy and firmly sanctioned popular sovereignty. Although grudgingly, Louis XVI approved it and the charter served as France’s constitution for two years until the National Convention replaced it. Shortly after its ratification, the National Constituent Assembly was reorganised into the Legislative Assembly.

The Constitution of 1791 did provide fundamental freedoms to citizens, but throughout the First Republic, they were not imposed. Following the dictatorial rule of Maximilien Robespierre during the Reign of Terror, civil liberties were curbed. As the Directory rose to ascendancy, the Constitution of the Year III – similar to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – was adopted, but due to the stringent checks and balances in place, it could never be strictly imposed. Furthermore, the administrations that followed until the Second French Republic: those of Napoleon, Louis XVIII, Charles X and Louis-Philippe [27], never enforced the liberties enshrined by the constitution. Despite the initial objective of the revolution being to empower the Third Estate, the middle class governed the nation – the lower class was ignored.

The Émigrés and the Flight to Varennes

Peasants were not the only oppressed social class during the French Revolution, as the National Constituent Assembly sequestrated many of the former nobility and clergy’s property and funds to rekindle the economy. Whilst contradictory to the right to property promulgated in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the national debt had to be paid off; thus, the Church’s property was nationalised, and nobles’ (outside the country) land was confiscated.

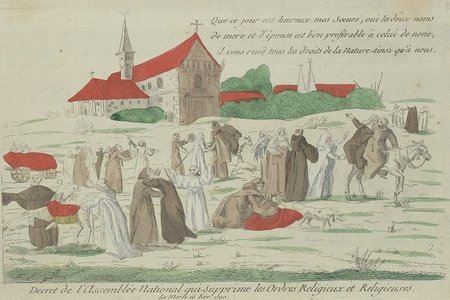

Compounded with a national disdain for the aristocracy – their homes were continuously raided – and the diminishing clergy’s authority, many former First and Second Estate members were impelled to emigrate from France. In the rest of Europe, where their status would earn them privileges – abolished in revolutionary France – they could make a more comfortable living. These nobles and clergymen were referred to as ‘émigrés’, and even nearly included the King.

After the promulgation of the Constitution of 1791 on 3rd September rendered France a constitutional monarchy, many – especially the left-wing Jacobins – wanted to go further and transform it into a republic. The monarchy would be abolished a year later; meanwhile, other European powers – still under the ‘Ancien Régime’ – suspected that the fall of the King would further destabilise France into turmoil. Simultaneously, many in the Legislative Assembly – especially Girondins – desired to disseminate the revolutionary ideals to the rest of the continent.

Beginning of the Revolutionary Wars

In February 1792, Austria and Prussia signed a military alliance to pressure France into renouncing its constitutionalist and anti-clerical ideals. Seeking to assert its dominance and spread liberalism among conservative Europe, the Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria on 20th April against the King’s wishes. Prussia signed a military alliance with Austria, forming the First Coalition and sparking the French Revolutionary Wars. Prussia soon issued the Brunswick Manifesto, threatening harsher military action if the Bourbon family were to be jeopardised; it was completely ignored, as evinced by the fact that Louis XVI was executed in January 1793.

That same year, France had captured the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium) and the First Coalition grew to include Great Britain, Spain, Portugal, Piedmont-Sardinia and other Italian states. The government soon abided by a ‘levée en masse’ policy, enforcing mass conscription – considering the internal revolts [28], France was in a precarious position.

Progress and End to the Wars

By 1795, the situation improved as France and Spain signed a truce and Prussia ceded all lands west of the Rhine River. Yet, the poor economic situation and lack of military organisation left France's success dubitable. The following year, the Italian campaign against Austria – spearheaded by Napoleon – was successfully concluded. The subsequent Treaty of Campo Formio (1797) ceded many Austrian-controlled and Italian lands to France – such as Nice, Savoy and part of Venice – enhancing the general’s popularity [29].

Soon after the War of the First Coalition concluded, Napoleon invaded Egypt, attempting to seize the nation, and Syria, from the Ottoman Empire; however, progress halted in mid-1798, with the final defeat occurring in 1801. Besides this failed campaign, in 1798, French territorial control expanded to the Batavian Republic (The Netherlands), the Helvetic Republic and some of the Italian Peninsula.

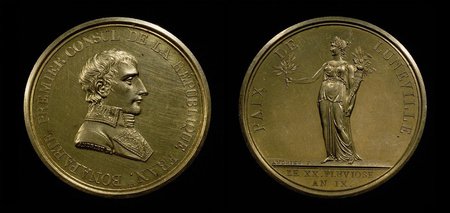

The Treaty of Amiens definitively concluded the war in March 1802, until fighting resumed the year after. With the French Revolution ending on 24th December 1799, the War of the Second Coalition was the last of the Revolutionary Wars; those from 1803 to 1815 (Third to Seventh Coalition) entirely occurred under Napoleon’s rule – collectively referred to as the ‘Napoleonic Wars’.

Descriptive Maps (courtesy of EmperorTigerstar)

_________________________________________________________________________________

Summary

CAUSES

- The combination of economic, political and social trends expedited the French Revolution

- The cost of living had become unaffordable due to the large national debt and deficit and the excessive tax burden on the Third Estate

- The estates system divided the upper-class citizens: clergymen (First Estate) and nobles (Second Estate), from the rest of the country (Third Estate), comprising 98% of the population

- The Enlightenment fostered nationalism, collectivism and liberalism, securing the bourgeoisie’s discontentment with the political system

- The corrupt and weak king, Louis XVI obstinately refused any change

THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY

- The National Assembly was the first revolutionary governing body, quickly succeeded by the similar National Constituent Assembly

- It recognised the King as sovereign but usurped his powers, intending to materialise the people's call for equality and liberty

- Due to the extreme inequality between the estates, with the First and Second Estates having many political and financial advantages over peasants, merchants and the bourgeoisie, the Estates-General convened to reach a compromise between their interests

- The Estates-General of 1789 was undemocratic and led to Third Estate representatives and a few clergymen and nobles to set up a National Assembly, effectively seizing most political power from the King and his cabinet

- They took the Tennis Court Oath, pledging not to disband until a constitution was drafted – to become 'something in the political order'; Louis XVI initially rejected the National Assembly, but as violence proliferated, he acquiesced and accepted their legitimacy in the séance royale

- With the National Constituent Assembly succeeding in centralising political power into the Third Estate, citizens were inspired to protest further, leading to the Paris Commune and the Storming of the Bastille

TOWARDS A CONSTITUTION

- The National Constituent Assembly was tasked to develop a constitution to enshrine rights for citizens, especially as violence among the sans-culottes increased

- The August Decrees abolished feudalism, the spoils system and privileges for the nobility and clergy, intending to make the three estates more equal

- The 'Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen' promulgated liberal and egalitarian principles, granting every individual (with exceptions) equal rights and fundamental freedoms, such as that of expression and that to own private property

- It solidified liberalism, nationalism and constitutionalism as core tenants of the French Revolution

- The Civil Constitution of the Clergy decreased the power of the Church and the clergy, rendering the revolution secularist

- The Constitution of 1791 mandated the principles promoted in the Declaration of the Rights of Man – but only granted those political to 'active' citizens – and centralised political administration

- It also established France as a constitutional monarchy committed to popular sovereignty

- For the most part, constitutional progress only favoured the bourgeoisie; peasants' lives were improved socially, but they remained politically and economically oppressed; nobles and clergymen were severely deprived of their assets and privileges – hence why many fled from France (émigrés)

- About to be bound to a constitution, Louis XVI attempted to leave the country but was stopped (Flight to Varennes), deeply humiliating him; this episode popularised calls for republicanism

WAR WITH EUROPE

- In February 1792, Prussia and Austria allied against France to counter the revolution; the National Constituent Assembly declared war on Austria on 20th April

- The First Coalition grew to include Great Britain, Spain, Portugal, Piedmont-Sardinia and other Italian states as well; France initially struggled but eventually captured the Austrian Netherlands, western territories of the Holy Roman Empire, and some Italian states

- The Treaty of Campo Formio (1797) ended the War of the First Coalition and boosted Napoleon's popularity considerably

- In 1798, Napoleon attempted to seize Egypt from the Ottoman Empire, but his campaign failed and ceased in 1801

- The Second Coalition formed in 1798 and ended in 1802 with the Treaty of Amiens; Austria was defeated again and France gained more lands throughout Western Europe

Notes

[1] Whilst the American Revolution was the main conflict precipitating the national debt, other eighteenth-century conflicts played a crucial role, such as the War of Spanish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. Involvement in these conflicts – often unnecessary and merely decorative – was chiefly wrought by Louis XIV and Louis XV.

[2] The livre was the national currency of France at the time – it was replaced by the franc in 1795. Ten billion livres would be the modern equivalent of approximately €750 million, or $830 million.

[3] In this context, a tithe was a contribution to a religious institution collected as a tax. Tithes were usually a tenth part of the respective tax; in this context, they equated to approximately 17% of one's income tax.

[4] Venality was the sale of an office in exchange for a considerable sum of money. In anterevolutionary France, the title of a noble would be sold to some middle-class citizens, bestowing them the privileges associated with the upper class.

[5] Secularism posits the separation of religion and clerical intervention from state affairs. Due to widespread piety, the authority of the Papacy and the Divine Right doctrine, most sovereigns embraced religious 'meddling' in government, but the Enlightenment challenged such assumptions about religion.

[6] The First Industrial Revolution oversaw the mass development of factories, which grouped workers and permitted them to discuss ideas and share grievances.

[7] The National Constituent Assembly was replaced by the Legislative Assembly on 1st October following the enactment of the Constitution of 1791; its main difference lay in the inclusion of political parties instead of factions representing the former estates – so, bourgeoisie, clergymen and some nobles. The Legislative Assembly was more resemblant to a modern parliament, with a clear divide between left-wing, right-wing and centrist politicians, whereas the National Constituent Assembly contained little ideological divides between representatives.

[8] Many clergymen were village abbots – therefore, poor – and some nobles leaned more towards the bourgeoisie class than the upper class, culminating in the minor presence of First and Second Estate members in the National Assembly.

[9] Land was predominantly acquired through venality – earning a noble title. Very few Third Estate members could afford to invest in a land purchase.

[10] A guild was a medieval association of merchants and craftsmen united to defend their interests, especially in countering poor working conditions or low salaries.

[11] As a gesture of increased representation, the number of Third Estate members totalled approximately double that of each of the other estates; out of 1,139 deputies, 578 were Third Estate (mostly bourgeoisie) citizens, 291 were clergymen, and 270 were nobles. However, each estate was allocated one vote on legislation, rendering the Estates-General unrepresentative of the French population, 98% of which were in the Third Estate.

[12] Since the monarch essentially determined the law, the Tennis Court Oath was unsurprisingly illegal as it contradicted the King's wishes. Nevertheless, Louis XVI tactfully deemed it legal (despite this not being the case) to appear more populist.

[13] At the time – and to a lesser extent, nowadays – most political action occurred in France's capital, Paris. In fact, Paris saw the beginning of the revolution with the Storming of the Bastille. Contrastingly, many other cities – and virtually all rural areas – were relatively untainted by revolts at first, so extensive action by the National Assembly was needed to extend the revolution nationwide.

[14] 'Ancien régime' refers to the 'old rule' of absolutism and Divine Right, later replaced by republican and constitutional governments. The conservatism associated with anterevolutionary France was reverted to allow liberal reform.

[15] The Paris Commune of 1789-1795 was an autonomous municipal government of Paris politically independent from the rest of France, performing such functions as tax collection and public works. A similar government was established in the city in 1871 following France's defeat in the Franco-German War.

[16] 'Censual' means 'of a cens' – a due paid to a seigneur (generally, a member of the First or Second Estate under whom one is subjected) in recognition of their title.

[17] 'Pays d'états' were financial districts, forming part of the généralités (administrative regions) into which France was divided. This perhaps replaced provincialism with a more centralised government, echoing the calls for nationalism.

[18] Before the 'Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen', other charters of human liberties had been drafted in Europe but were often indirect, vague or poorly enforced; the 'Magna Carta' (1215) and the English 'Bill of Rights' (1689) are examples. In 1776, the United States Declaration of Independence laid out certain inalienable principles, inspiring the 'natural rights' doctrine adopted by the Declaration of the Rights of Man. A few weeks after the latter was drafted, the U.S. 'Bill of Rights' was created.

[19] 'Natural law' theory posits the existence of certain universal rights ingrained in human nature – not guaranteed by law, but by "God, nature, or reason". This contrasts with 'positive law' – rights mandated by the state. English political theorist John Locke professed the inherent quality of certain rights, discovered through reason and that cannot be suppressed; the government should ensure that these are constantly acknowledged.

[20] 'Social contract' is a hypothetical compact between the 'ruler' (government) and the 'ruled' (citizens), implying that the government should rule by respecting and guaranteeing citizens' liberties and that citizens ought to give their consent to such government and safeguard each other's freedoms.

[21] 'Separation of powers' is the division of state authority into distinct branches carrying out different functions, typically in the 'trias politica' model – legislative (enacting laws), executive (enforcing laws), and judicial (defending the law). Montesquieu was its chief proponent, delineating the tripartite model in his treatise 'The Spirit of Laws'.

[22] 'Checks and balances' is the principle that each branch of government should be empowered to prevent overbearing actions from other branches, allowing a fairer distribution of power. The phrase was coined by Montesquieu, although English jurist William Blackstone also influenced its inception.

[23] Economic liberalism generally encompasses empowering private businesses to manufacture goods and provide consumer services without much government involvement in producing or managing assets or regulation. Besides free market dominance, economic liberals typically advocate low tariffs to stimulate international trade.

[24] Collectivism is the prioritisation of the interests of a group rather than the individual; in this context, it favours bolstering society in constructing a solid nation rather than ameliorating individual rights.

[25] Nationalisation is the transfer of ownership of an asset, property, business or industry from private to state control. The National Constituent Assembly seized control of many churches and property belonging to the clergy, mostly to sell them off.

[26] Egalitarianism is the doctrine that all individuals are equal in value and deserve equal rights, privileges and opportunities, regardless of their characteristics. Whilst the French Revolution was liberal, it disregarded the rights of women, slaves and people of colour; some Montagnards opposed such discrimination.

[27] The aforementioned leaders were all authoritarian sovereigns. Under their rule, France was run as a near dictatorship, with little consideration for the human liberties granted by the constitutions drafted in the French Revolution.

[28] Due to the Committee of Public Safety's extremist violent imposition of revolutionary principles, fervent attitude against the monarch, and antipathy towards the Church, a counterrevolution occurred, beginning with the War in the Vendée.

[29] Napoleon's success in his military campaigns earned him much respect from the French population; he would use his solid reputation to stage a coup against the Directory and become sovereign of France. Whilst his Egypt Campaign was a failure, it did not taint his image, for the press did not cover the incident.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed chronologically in order of use.

CAUSES

THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY

- Lumen Learning

- World History Encyclopedia

- World History Encyclopedia

- Alpha History

- Brittanica

- Wikipedia

TOWARDS A CONSTITUTION

WAR WITH EUROPE

MISCELLANEOUS