The French Revolution was Surprisingly Not That Liberal

Blog by

Last updated: Saturday March 30th, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Saturday March 30th, 2024

Report this blog

+8

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the reasons why the French Revolution contradicted many of its liberal principles promised to citizens. Despite being very avant-garde, its constitutional ideals were executed inadequately, such that most citizens remained without rights.

It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article.

It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article.

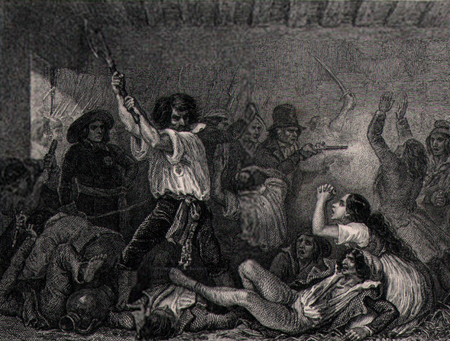

An execution during the Reign of Terror: a period when civil liberties were largely disregarded

Overview

The French Revolution was the first populist revolt in Europe, motivated purely by the people’s demands for better living conditions and more liberties. From its inception on 14th July 1789, revolutionaries unanimously consented to strive for an improved political and social situation acknowledging and respecting the conditions and value of every French citizen. Yet, as a government formed to rule the country, this commitment to populism was partially neglected and traded for a commitment to political expediency.

Flawed Democracy

The concept of a democratic government committed to the people’s exigencies – supposedly ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’ (Abraham Lincoln) – was not fulfilled. Following the Tennis Court Oath on 20th June 1789, the National Assembly became the effective French governing body. Most of the representatives were bourgeoisie members (hence, the Third Estate), reflecting the population of the country, 98% of which comprised Third Estate citizens; Abbé Sieyes considered them to be ‘nothing in the political order’, desiring to ‘become something’ (‘Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État’). In representing their interests, the Assembly became the first democratic government in Europe.

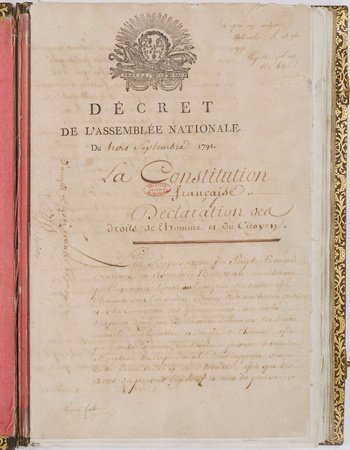

Whilst progress was made towards popular sovereignty, the bourgeoisie-controlled government disregarded the lower-class necessities, constituting 80% of the French population. The Constitution of 1791 manifested the flaws in the French Revolution’s execution of democracy, distinguishing between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ citizens. Only the former category – including males over twenty-five paying taxes equivalent to three days of labour (less than fifteen per cent of the population) – were bestowed political rights – to vote and participate in local and national politics; this recurred throughout the Revolution. Furthermore, the Directory – governing France from 1795 to 1799 – was disproportionately influenced by the aristocracy, meaning that corruption ran rampant and many economic reforms favouring the proletariat – such as the General Maximum (and other price and wage controls) – were repealed. Throughout the Revolution, the vast majority of the French remained politically underrepresented.

The Constitution of 1791: the first French constitution, bestowing human rights, but limiting those political to 'active' citizens

Authoritarian Government

The French Revolution also aimed to expunge authoritarianism, special favours and plutocracy from the political system, yet the same vices overshadowed the revolutionary administration. King Louis XVI – an absolute monarch – was gradually divested of his potency. In swearing the Tennis Court Oath, the National Assembly usurped many of his powers; eventually, the King became bound to a constitution. The monarchy was finally abolished on 21st September 1792. The Constitution of Year III also implemented many checks and balances and division of powers, mindful of eliminating any potential autocracy.

However, political inefficacy, factionalism, and tyranny persisted in the National Convention and Directory’s administrations. The Insurrection of 31 May-2 June purged Girondins from the National Convention. Thereafter, Maximilien Robespierre centralised power under the Committee of Public Safety – acting as a police force to enforce his ideals – enacting inordinate, extremist and mostly sanguinary measures, making “terror on the order of the day” (Camille Desmoulins). This overbearing attitude recurred during the Thermidorian Reaction when Jacobins and Robespierreans were expelled from the government. Moreover, the political factionalism during the Directory rendered the administration ineffective, as the Montagnards and royalists/Girondist-leaning contended for control, culminating in the Coup of 18 Fructidor. The Directory was also culpable of spoils and corruption, rendering it unpopular, such that the beloved general Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew it in the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799, making him First Consul – an effective dictator. Despite the Revolution’s devotion to curtailing administrative powers and doing away with despots, it ended with France being led by an autocrat.

Maximilien Robespierre: Jacobin/Montagnard who controlled the Committee of Public Safety from July 1793 to June 1794, centralising all political power under himself, rending France an autocracy

Deprivation of Human Rights

The French Revolution’s primary accomplishment – promulgating and mandating liberal principles to safeguard every citizen’s rights – was undermined by government oppression or inactivity. Shortly after the National Constituent Assembly’s formation, the August Decrees – issued in August 1789 – rescinded the feudal system and any privileges previously borne by the First and Second Estates and strictures on the Third Estate, meaning that no formal financial or social distinctions between social classes could be made. They preceded the ‘Le Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen’ – a keystone document of the Enlightenment liberal ideals, guaranteeing “liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression” to every ‘man’ (Article II) – deemed equal and free agents. For instance, the rights to private property, free speech, freedom of the press, prevention from arbitrary arrest and equality before the law were granted.

Whilst mandated in the Constitution of 1791, these liberal ideals were not extensively enforced throughout the Revolution. During Robespierre’s Reign of Terror, civil liberties were blatantly disregarded, as the Committee of Public Safety continuously intruded on citizens’ lives and detained them from criticising the government. In fact, freedom of expression and association were restricted from 1792 onwards due to widespread massacres or censures on certain political parties, as observed in the White Terror. The most infamous act of the Terror – the Law of Suspects’ enactment – contemned the judicial reform and presumption of innocence proclaimed in the Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen, as many citizens were declared guilty and executed or imprisoned without a fair trial. Moreover, the Directory’s executive impotency translated to insufficient enforcement of constitutional rights.

The massacre of Jacobin prisoners during the White Terror: those affiliated with the Thermidorian movement killed Jacobins - a breach of freedom of association and speech

Conclusion

The French Revolution’s progress towards democracy, popular sovereignty, political fairness, constitutionalism and human rights – its populist ideals – was subverted by the government’s – mostly Robespierre and the Directory’s – prioritisation of securing its interests. Whilst certainly liberal in principle, the Revolution was practically a continuation of the Ancien Régime rule, at least for lower-class citizens – 80% of France.

However, a very interesting blog!

Be sure to keep writing! The French Revolution is such an interesting topic, and you can present it brilliantly, as you have shown!