Why did France's Last King Fail?

Blog by

First published: Monday April 15th, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Monday April 15th, 2024

Report this blog

+5

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the the reasons behind the downfall of the July Monarchy, headed by King Louis Philippe I, and the causes of the French Revolution of 1848. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

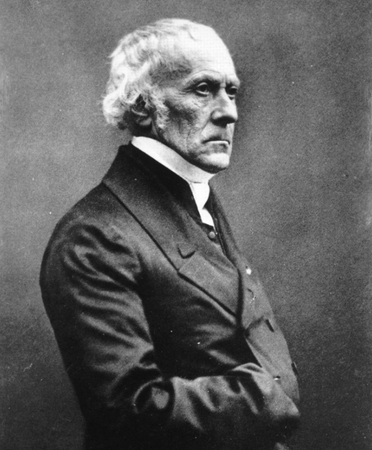

King Louis-Philippe I bearing the French tricolour following the July Revolution (1830): his relatively liberal views on government—in fact, he was the only French king to accept the tricolour: a symbol of the French Revolution of 1789, and also the only one to wear trousers instead of breeches—made him popular among the masses and allowed for his ascendancy to the throne in 1830, earning him the moniker of "citizen king", but he was nonetheless disconnected from the French populace and ruled in an authoritarian fashion

Background and Overview

On 9th August 1830, Louis-Philippe I, Duke of Orleans (1773–1850) was proclaimed King of the French after the Trois Glorieuses [1] expedited his predecessor Charles X’s abdication, consolidating the July Monarchy. The King’s liberal background rendered him an acceptable compromise between France’s two leading political factions. These were the Legitimists, who proposed Charles X’s heir, Henri, Count of Chambord, and republicans, who favoured the establishment of a second republic. Louis-Philippe was bound to the Charter of 1830, which reduced the monarchy’s authority, mandated parliamentarianism and granted more civil liberties, such as increasing freedom of the press and expanding suffrage to the privileged bourgeoisie.

However, hopes of a moderately liberal administration were eradicated in the 1840s, as the King merely seemed a more tolerable repeat of the absolutist Charles X. He was eventually forced to step down on 24th February after a nationwide revolt (the French Revolution of 1848). The July Monarchy amounted to a failed attempt at preserving constitutional monarchy in France in an era of necessitated social reform, especially for workers; some historians even dub it an ‘anachronism’ in an intensely liberal political climate. French political analyst Alexis de Tocqueville perfectly illustrated the turbulent social environment during the closing stages of Louis-Philippe’s reign:

‘We are sleeping together in a volcano [...] A wind of revolution blows, the storm is on the horizon’.

Political Inefficacy and Authoritarianism

Plagued with the label of a ‘compromise king’, Louis-Philippe could not appease any political faction in the National Assembly [3], especially the liberals/constitutionalists [4] who had secured him following the July Revolution. He initially embraced the Charter of 1830’s reforms aimed at popular sovereignty [5], reducing the poll tax from 300 francs to 200 [6], thereby expanding the electorate from 0.3% of the population (1830, pre–revolution) to 0.5% of the population (1830, post–revolution) and eventually to 0.7% (1848), and extolling the Guizot Law of 1833 establishing primary schools in every French commune.

Additionally, throughout the 1830s, his cabinet incorporated several left-wing politicians, such as Jacques Laffitte (prime minister from 1830 to 1831) and Adolphe Thiers (prime minister in 1836 and 1840), rendering him relatively popular among the elected moderates [7] in the Chamber of Deputies.

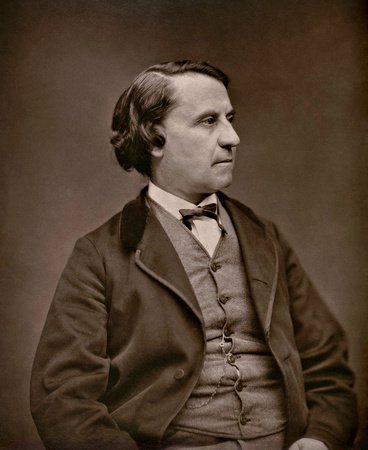

François Guizot: leader of the Resistance Party, Minister of Public Education (1834–1836, 1836–1837), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1840–1848), Prime Minister (1847–1848); an emblem of the July Monarchy's conservatism [2]

However, Louis-Philippe grew increasingly dogmatic after the early 1830s, refusing to accept liberal concessions and enhance the political representation of the lower and lower–middle classes, collectively comprising approximately 80% of France’s population at the time. Most notably, he sanctioned the conservative policies of François Guizot (one of the Resistance Party leaders throughout the July Monarchy’s duration and prime minister from 1847 to 1848), such as limiting suffrage to the elite and the prohibition of republican publications in 1834. The Chamber of Deputies was also rife with corruption and patronage.

Members of the centre-right Resistance Party were admitted hegemony over legislative powers, with the centre-left Movement Party unable to influence the legislature much, especially considering every election from 1842 onwards resulted in sweeping majorities for the former. Left-wing figures’ propositions were stifled: republican insurrectionist Armand Barbès and socialist activist Auguste Blanqui were condemned to life imprisonment in 1839 and 1840, respectively.

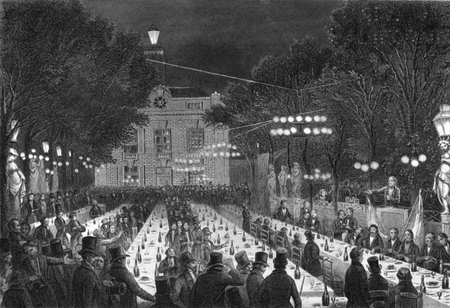

The constant suppression of labour revolts tarnished the King’s image among the urban working-class ‘sans-culottes’; the partial dismemberment of the Parisian National Guard in the 1830s, established during the French Revolution of 1789, also did him no favours. Louis-Philippe’s authoritarianism wholly manifested in February 1848 when he embraced F. Guizot’s abolition of mass banquets serving as political discussion agglomerations—the definite spark to the French Revolution of 1848.

Foreign events, namely the Sicilian Revolution of 1848 and the Chartist Movement in the United Kingdom, contributed to the national uprising. Moreover, throughout the July Monarchy’s duration, the King persistently faced opposition from Legitimists/ultraroyalists [8], as well as Bonapartists [9]—future emperor Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte staged two failed coups d’état in 1836 and 1840—cementing his lack of political support.

Members of the centre-right Resistance Party were admitted hegemony over legislative powers, with the centre-left Movement Party unable to influence the legislature much, especially considering every election from 1842 onwards resulted in sweeping majorities for the former. Left-wing figures’ propositions were stifled: republican insurrectionist Armand Barbès and socialist activist Auguste Blanqui were condemned to life imprisonment in 1839 and 1840, respectively.

The constant suppression of labour revolts tarnished the King’s image among the urban working-class ‘sans-culottes’; the partial dismemberment of the Parisian National Guard in the 1830s, established during the French Revolution of 1789, also did him no favours. Louis-Philippe’s authoritarianism wholly manifested in February 1848 when he embraced F. Guizot’s abolition of mass banquets serving as political discussion agglomerations—the definite spark to the French Revolution of 1848.

Foreign events, namely the Sicilian Revolution of 1848 and the Chartist Movement in the United Kingdom, contributed to the national uprising. Moreover, throughout the July Monarchy’s duration, the King persistently faced opposition from Legitimists/ultraroyalists [8], as well as Bonapartists [9]—future emperor Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte staged two failed coups d’état in 1836 and 1840—cementing his lack of political support.

The 'campagne des banquets' (banquets campaign): the suspension of mass gatherings as these was perceived as authoritarian and contradictory to the Charter of 1830's principles, expediting the French Revolution of 1848

Economic and Labour Struggles

Economic hardships induced several protests organised by urban workers, diminishing Louis-Philippe’s political security. Socialism became widely popularised in the 1830s and 1840s as many prominent left-wing writers such as Louis Blanc and Louis Blanqui promulgated the perceived failings of the capitalist system: a product of the a href="https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution">First Industrial Revolution [11]. As mass urbanisation and the adoption of innovations—including primitive hot blast stoves—transformed French society during Louis-Philippe’s reign, factory workers became impoverished and malaise adumbrated such cities as Paris.

Pioneering socialist utopian thinker Charles Fourier encapsulated the proletariat’s poor conditions owing to the bourgeoisie’s repudiation of reform:

‘By reducing [the present condition of the domestic and salaried classes to…] slavery, civilisation, on the rebound, imposes chains upon those who seem to dominate. Thus, notables do not dare to amuse themselves openly at times when the people suffer from poverty’.

Louis Blanc: socialist writer and revolutionary; later a Socialist Republican member of the provisional government of the Second Republic in 1848

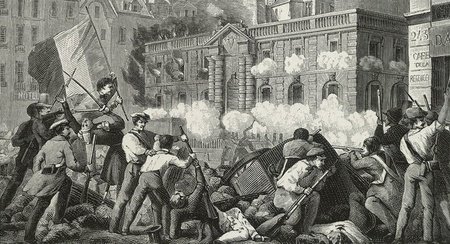

The government’s reluctance to increase wages and acknowledge workers’ rights fuelled several revolts throughout the July Monarchy. The three Canut Revolts (in 1831, 1834 and 1848) resulted from the refusal to impose a minimum wage to maintain a comfortable standard of living for Lyon silk merchants. A more considerable protest occurred in Paris in 1832 opposing the King’s reign (the June Rebellion), immortalised in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables; 800 civilians were killed or wounded.

Louis-Philippe violently suppressed this opposition and refused to adapt to the increasingly quasi–syndicalist/socialist [12] political climate. This was epitomised by the corrupt appointment of conservative banker Casimir Pierre Périer as prime minister in 1831, who cracked down on mass labour assemblages. The King also endorsed the prohibition of the banquets campaign. Although one can argue that these policies guaranteed security in France, it can also be argued that some concessions to workers and liberals needed to be made to prevent these protests in the first place.

The economic downturn from 1846 to 1848 impoverished millions and escalated unemployment; such urban cities as Roubaix had 60% unemployment in 1847, and one-third of Paris was on social welfare. Meanwhile, F. Guizot’s ‘enrichissez–vous’ policy (the promotion of industriousness to enrich oneself) aggravated matters. It was perceived as blatantly disconnected from the status quo, unlike L. Blanc’s call for the right to work, which resonated with workers.

Louis-Philippe violently suppressed this opposition and refused to adapt to the increasingly quasi–syndicalist/socialist [12] political climate. This was epitomised by the corrupt appointment of conservative banker Casimir Pierre Périer as prime minister in 1831, who cracked down on mass labour assemblages. The King also endorsed the prohibition of the banquets campaign. Although one can argue that these policies guaranteed security in France, it can also be argued that some concessions to workers and liberals needed to be made to prevent these protests in the first place.

The economic downturn from 1846 to 1848 impoverished millions and escalated unemployment; such urban cities as Roubaix had 60% unemployment in 1847, and one-third of Paris was on social welfare. Meanwhile, F. Guizot’s ‘enrichissez–vous’ policy (the promotion of industriousness to enrich oneself) aggravated matters. It was perceived as blatantly disconnected from the status quo, unlike L. Blanc’s call for the right to work, which resonated with workers.

The anti–monarchist June Rebellion (Paris Revolt of 1832): many urban residents were discontent with Louis-Philippe owing to his obstinate reluctance to recognise workers' rights and enact liberal reforms; such protests destabilised his reign

Foreign Policy Mediocrity

Whilst arguably not as damaging as the other two factors, Louis-Philippe’s singularly unimpressive record with foreign affairs did little to augment his popularity. In light of his status as a product of a revolution—a stain for the absolutist nations comprising the Concert of Europe (except for the United Kingdom, which was a parliamentary monarchy)—he attempted a compromise between compliance with Metternichian diplomacy and hawkish expansion of French influence.

This approach hardly satisfied any of the two and left the French populace hankering for national pride reminiscent of the Napoleonic age. Italian historian Silvio Berardi wrote of the King's ambivalence:

'The moderate character of Louis Philippe’s monarchy was confirmed in its foreign policy. It was contrary to any adventure in the international field and much less inclined to support the [...] uprisings that broke out in that period'.

Spanish Duchess Infanta

Luisa Fernanda: her marriage to Antoine,

Duke of Montpensier, virtually eradicated Anglo–French relations

Louis-Philippe resisted the temptation to annex Belgium following its secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830 and averted national humiliation by dismissing then–Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers’ support of Muhammad Ali Pasha during the Oriental Crisis. He also refused to support the Italian unification/republican movements of 1830–31 or the November Uprising (aimed at Polish independence from Russia) in compliance with the other European great powers.

However, the Affair of the Spanish Marriages severely strained Anglo-French relations, reversing Louis-Philippe’s progress in being the first French king to visit British territory since the captivity of John II in 1356. He married off the French Duke of Montpensier, Antoine, to the Spanish heir presumptive Infanta Luisa Fernanda instead of a member of the British Saxe-Coburg-Gotha royal house, despite F. Guizot previously promising to do otherwise.

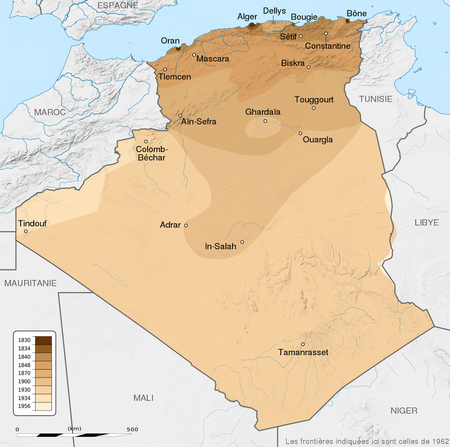

Another foreign policy fiasco was the poorly conducted French conquest of Algeria, which began at the end of Charles X’s reign. It dragged on during the July Monarchy’s duration and wrought considerable expenses—it only definitively concluded in 1903. Consequently, Louis-Philippe oversaw practically no foreign policy successes—only avoidances of trouble or downright failures. One can argue that his non–interventionist, reticent approach succeeded as it maintained healthy French relations with the great powers. Nonetheless, the public desired some 'glorious' conquest to restore French military prestige abroad as Napoleon had done a few decades prior.

However, the Affair of the Spanish Marriages severely strained Anglo-French relations, reversing Louis-Philippe’s progress in being the first French king to visit British territory since the captivity of John II in 1356. He married off the French Duke of Montpensier, Antoine, to the Spanish heir presumptive Infanta Luisa Fernanda instead of a member of the British Saxe-Coburg-Gotha royal house, despite F. Guizot previously promising to do otherwise.

Another foreign policy fiasco was the poorly conducted French conquest of Algeria, which began at the end of Charles X’s reign. It dragged on during the July Monarchy’s duration and wrought considerable expenses—it only definitively concluded in 1903. Consequently, Louis-Philippe oversaw practically no foreign policy successes—only avoidances of trouble or downright failures. One can argue that his non–interventionist, reticent approach succeeded as it maintained healthy French relations with the great powers. Nonetheless, the public desired some 'glorious' conquest to restore French military prestige abroad as Napoleon had done a few decades prior.

Chronological progress of the French conquest of Algeria: French military campaigns were often costly and drawn–out, leaving Louis-Philippe without any notable foreign policy successes to claim

Conclusion

The July Monarchy was intended to redeem the monarchy’s existence in France and enact several liberal reforms well-suited for the rise of socialism, republicanism and Chartism in the mid-nineteenth century. However, King Louis-Philippe only managed to compromise his way to 1848 by occasionally offering mere token support of liberal policies, proving dissatisfactory for the proletariat and members of the Movement Party.

Eventually, his authoritarian measures—namely, violently quelling labour protests, hindering freedom of thought, expression and association, and supporting François Guizot—caught up with him in February 1848 as he was forced to abdicate and the French monarchy was perpetually abolished. Inaction in the face of economic downturn and international affairs expedited his downfall. American author Benjamin Perley Poore summarily described the July Monarchy’s demise in The Rise and Fall of Louis Philippe:

'Never did a ruler [Louis-Philippe] more completely falsify the confiding hopes of his countrymen […], unsparingly sacrificing the moral and material interests of the French people to a miserable nepotism'.

Notes

[1] 'Trois Glorieuses' is French for 'the Three Glorious Days'—also known as the July Revolution.

[2] In fact, the preamble to the Communist Manifesto states: 'A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies'; Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels—the authors of the manifesto—regard François Guizot as an impediment against the abounding liberal and socialist calls for change.

[3] Since the Bourbon Restoration, the National Assembly was the bicameral French legislature, comprising the lower house, the Chamber of Deputies (the members of which were elected by the French populace), and the Senate (nominated by the King). This is not to be confused with the modern National Assembly: the lower house of the French Parliament, with the upper house being the Senate.

[4] In nineteenth-century politics, political parties were loosely defined, and sources often contradict each other on their respective ideologies. The liberals in the Chamber of Deputies are generally grouped into the centre-left Movement Party or the syncretic Doctrinaires. However, the Doctrinaires were mostly affiliated with the centre-right Resistance Party, which dominated French politics in the 1840s. In fact, the centre-right hegemony over legislation in the latter half of Louis-Philippe's reign, amounting to little social reform, greatly contributed to his downfall. The aforementioned parties generally supported the Orleanist regime until 1848; only the Legitimists and Republicans—both minor factions—persistently opposed Louis-Philippe.

[5] Popular sovereignty—a core democratic tenet—literally means the people (‘popular’) rule (‘sovereignty’), by which the people’s will dictates state affairs.

[6] Throughout the July Monarchy, only aristocrats and the privileged bourgeoisie—factory owners, wealthy merchants and members of the managerial class—earned anywhere near the amount required to vote in legislative elections, hence why the electorate only constituted under one per cent of the French population.

[7] In the Chamber of Deputies, moderates generally aligned with the centre-right Resistance Party and, to a lesser extent, the centre-left Movement Party. The former was more Orleanist (supportive of Louis-Philippe's rule).

[8] Ultraroyalists, also known as ultras, advocated a return to absolutism and the ancien régime. They typically aligned with the Legitimists and had previously supported Charles X's reign.

[9] Bonapartists advocated the restoration of former Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte's lineage—therefore, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (his nephew) as sovereign. Most of the French populace viewed Napoleon's reign favourably due to his domestic reforms and unparalleled military success. This was reflected in the 1848 French presidential election, in which Louis-Napoleon was elected as president of the Second Republic by a margin of 74%.

[10] In Marxist thought, the proletariat is the working class—predominantly factory workers—and the bourgeoisie is the managerial class—predominantly factory owners. This hierarchy is typical of a capitalist system and prevails in Western society.

[11] Most historians agree that there have been four industrial revolutions (periods of rapid industrialisation). This blog focuses on the first one, occurring from c. 1760 to c. 1840.

[12] Syndicalism is the ideology advocating allocating considerable authority to trade/labour unions in dictating workers' conditions and status. 'Quasi–syndicalism' is used since the first trade unions had not emerged yet, but some primitive workers' organisations still existed, such as guilds.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories. The links appearing throughout the blog should also be consulted.

BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW

- Reign of Charles X

- July Revolution

- Legitimists and Opposition to Louis-Philippe

- Republicans and Opposition to Louis-Philippe

POLITICAL INEFFICACY AND AUTHORITARIANISM

- Role of François Guizot

- Electoral System of the July Monarchy

- Legitimists and Opposition to Louis-Philippe

- Republicans and Opposition to Louis-Philippe

ECONOMIC AND LABOUR STRUGGLES

FOREIGN POLICY MEDIOCRITY

- Foreign Policy of Louis-Philippe (1)

- Foreign Policy of Louis-Philippe (2)

- Concert of Europe and European Diplomacy (1)

- Concert of Europe and European Diplomacy (2)

MISCELLANEOUS

- Fall of the July Monarchy

- Republicanism in 1848

- Biographies of Louis-Philippe

- Rise and Fall of Louis-Philippe

- Revolts in France During the July Monarchy

SUGGESTED VIEWING

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning THE JULY MONARCHY. The rest can be accessed from my History series.