Did the Congress of Vienna Succeed?

Blog by

First published: Monday April 1st, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Monday April 1st, 2024

Report this blog

+5

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the effects of the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) on European affairs and diplomacy. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

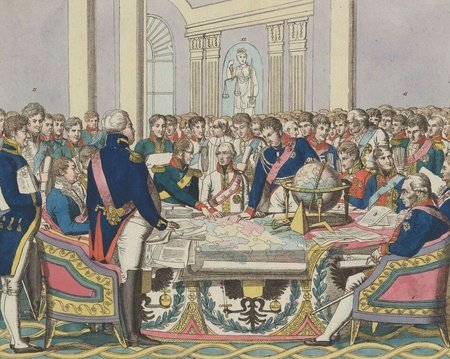

European leaders and representatives at the Congress of Vienna

Overview

The Congress of Vienna was the first of the diplomatic conferences between European great powers in the Pax Britannica (1815–1914), collectively known as the Concert of Europe. Convening after the War of the Sixth Coalition (1814) and again following the War of the Seventh Coalition (1815) [1], the then–predominant European nations intended to restructure the political order and redraw the borders of sovereign states. The great powers at the time were the United Kingdom (represented in conference by Viscount Castlereagh), France (rep. Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord), Prussia (rep. Karl August von Hardenberg), Austria (rep. Prince Klemens von Metternich) and Russia (rep. Tsar Alexander I) [2]. To preserve international and national peace to avert a repeat of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, conservatism and orthodoxy were to dictate foreign affairs for the Concert of Europe’s duration, no less than in the Congress of Vienna. This resolute yet intransigent doctrine predictably actuated the great powers’ aims of restoring peace and order with mixed success.

Background and Aims

France’s volatile state throughout the 1789 French Revolution and the continental conflict resulting from it, owing to a rebuke of the conservative status quo, motivated the great powers to stifle most principles resemblant of the revolution to maintain law and order in Europe. The French Revolution was committed to liberalism and democracy [3]; it eradicated the absolutist ancien régime [4]—prevalent in France since the centralisation of power under the Bourbon dynasty with Henry IV’s ascension to the throne in 1589.

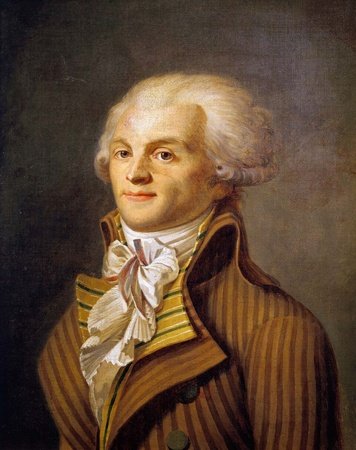

As such, the abolition of the monarchy and the subsequent establishment of the First French Republic in 1792 reversed centuries of relative political stability—albeit also despotism—in France. In fact, protests persisted throughout the revolution’s duration; Maximilien Robespierre’s Reign of Terror alone claimed 50,000 citizens. Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power as a result of the governmental instability of the revolution, and his sovereignty led to the then–most immense war in European history (except for the Thirty Years' War) [5], destabilising the continent since 1792 and costing over five million lives (according to David Gates and Charles J. Esdalie).

Maximilien Robespierre, leader of the Committee of Public Safety which had unmitigated control over France from mid–1793 to mid–1794: he embodied the political turmoil prevalent in revolutionary France as a result of the absence of an absolute monarchy

Representatives at the Congress of Vienna regarded two primary reasons behind France’s initial success in the Napoleonic Wars: the abundance of impotent nations bordering France which could be conquered easily and the lack of coordination between European powers in quelling the French Revolution in the first place. Therefore, three conservative creeds would dictate continental affairs: balance of power, multipolarity and traditionalism. These aimed at suppressing the French Revolutionary principles of liberalism, republicanism, constitutionalism and nationalism—perceived as a harbinger of instability.

One of the prints from Spanish painter Francisco Goya's series The Disasters of War, also self–titled "Fatal Consequences of Spain's Bloody War with Bonaparte, and Other Emphatic Caprices" [6]: the sheer violence and havoc wrought by the Napoleonic Wars convinced representatives at the Congress of Vienna to prevent a repeat of such conflict at all costs

Balance of Power

To forestall the outbreak of continental war, delegates redrew the European borders to reinforce the balance of power—the equitable territorial power distribution between adjacent nations such that one does not dominate the other. Emperor Napoleon I’s conquest of continental Europe, with nearly all of it subjected or allied to the First French Empire in 1809, manifested the need for certain nations to be bolstered to resist invasion by another power—namely, France.

With Belgium being such an easy target for France to dominate, it was merged with the Netherlands, forming the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Northern Italy also proved too controllable, so it was reorganised; Piedmont [7] was strengthened by combining it with the Republic of Genoa, Savoy and Nice, and Lombardy and Venice were integrated to form the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia and annexed into Austria.

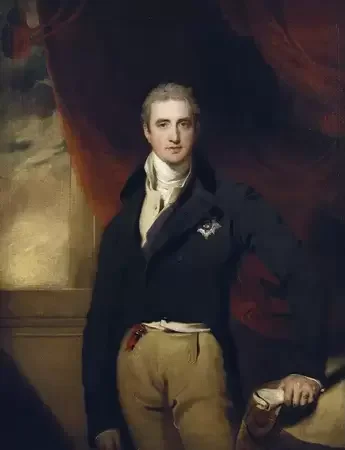

Prince Klemens von Metternich, the chief Austrian delegate in the Congress of Vienna: the preeminent architect of the Congress System and proponent of maintaining the ancien régime

With the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, a new confederation, the German Confederation, was formed, and the hundreds of states formerly comprising the Holy Roman Empire were reduced to thirty-nine, individually reinforcing them. For instance, Bavaria and Baden were enlarged to resist potential invasion. Prussia’s status as a great power was ensured, as it was given the Rhineland, Westphalia and parts of Saxony. Other amendments included the partition of the Duchy of Warsaw between Russia (obtaining most of it), Prussia and Austria, the transfer of several colonies to the British Empire, such as Malta, Ceylon and Guiana, and the establishment of a personal union between Norway and Sweden.

One pivotal affair the great powers did not tackle, which, in hindsight, they should have, was the territorial fate of the Ottoman Empire. Boasting the moniker "the sick man of Europe", its stability was challenged by the desire of constituent ethnicities to break free from the empire. In fact, Greece would partake in a successful war of independence just six years after the Vienna settlement from 1821 to 1832; similar conflicts ravaged the Balkans throughout the nineteenth century, culminating in the Eastern Question. Furthermore, under the Second Treaty of Paris (1815), France’s borders as of January 1790 were restored, a 700 million franc pecuniary indemnity was imposed, and most of the country was held under joint military occupation until this was cleared (in 1818).

Upon historical consideration, the balance of power doctrine can be regarded as the congress’ most venerable accomplishment. The borders forged would largely remain unaltered until the Italian and German wars of unification in the 1860s and a notable conflict between multiple European powers would only occur next in 1853 (the Crimean War). This indicates relative diplomatic security in the nineteenth century, whereas the eighteenth century was perpetually besmirched by hostilities—namely, the War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714), War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), Partition of Poland (1772–1795) and French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802).

One pivotal affair the great powers did not tackle, which, in hindsight, they should have, was the territorial fate of the Ottoman Empire. Boasting the moniker "the sick man of Europe", its stability was challenged by the desire of constituent ethnicities to break free from the empire. In fact, Greece would partake in a successful war of independence just six years after the Vienna settlement from 1821 to 1832; similar conflicts ravaged the Balkans throughout the nineteenth century, culminating in the Eastern Question. Furthermore, under the Second Treaty of Paris (1815), France’s borders as of January 1790 were restored, a 700 million franc pecuniary indemnity was imposed, and most of the country was held under joint military occupation until this was cleared (in 1818).

Upon historical consideration, the balance of power doctrine can be regarded as the congress’ most venerable accomplishment. The borders forged would largely remain unaltered until the Italian and German wars of unification in the 1860s and a notable conflict between multiple European powers would only occur next in 1853 (the Crimean War). This indicates relative diplomatic security in the nineteenth century, whereas the eighteenth century was perpetually besmirched by hostilities—namely, the War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714), War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), Partition of Poland (1772–1795) and French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802).

Europe in 1789, before the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

Europe in 1815, after the amendments made in the Congress of Vienna

Multipolarity and Alliances

The Congress of Vienna set a precedent for the great powers to undertake in the affairs of all European nations for the rest of the nineteenth century through irregular conferences. The Concert of Europe abided by the principle of multipolarity: the allocation of significant power in multiple states to dominate foreign affairs, whilst other less potent nations bear little to no influence. Until World War One, the nations boasting the status of a "great power" remained the same: the United Kingdom, France, Prussia (from 1871 onwards, the German Empire), Austria (from 1867 onwards, Austria-Hungary) and Russia; Italy would be occasionally consulted in the twentieth century.

Alliances were formed to safeguard the collaboration between member states of the Concert of Europe. The Congress of Vienna led to the Quadruple Alliance between the United Kingdom, Prussia, Austria and Russia [8]—later replaced by the Quintuple Alliance (1818) to incorporate France—and the Holy Alliance between Prussia, Austria and Russia contrived to quell European protests and preserve conservatism.

Viscount Castlereagh, the chief British delegate in the Congress of Vienna: he espoused a foreign policy of 'spendid isolation', linked to the United Kingdom's objection to coact with the European great powers

One can notice a contradiction here: since Prussia, Austria and Russia were affiliated with two alliances, they artificially had supremacy over the United Kingdom and France in the Concert of Europe. In fact, the latter two nations—both constitutional monarchies and relatively liberal compared to the other three absolute monarchies—were hardly interested in upkeeping conservatism in the continent; Viscount Castlereagh even deemed the Holy Alliance ‘a piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense’.

There was an inherent conflict of interest between the five great powers; they each had distinct principles and approaches to foreign policy. The United Kingdom and France adopted a policy of European isolationism for most of the first half of the nineteenth century, whilst the Holy Alliance powers intervened capriciously when they had an incentive to, not when they deemed it best for the Concert of Europe’s sake. For instance, Russia intervened in the Greek War of Independence to defend Greek nationalism despite being a member of the Holy Alliance intended to uphold the conservative status quo. The conservative principles enunciated in the Congress of Vienna seemed to collapse in the 1830 London Conference. The great powers acquiesced to Belgian demands and granted them independence from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands—another recognition of the right to self–determination [9], contradicting their aims.

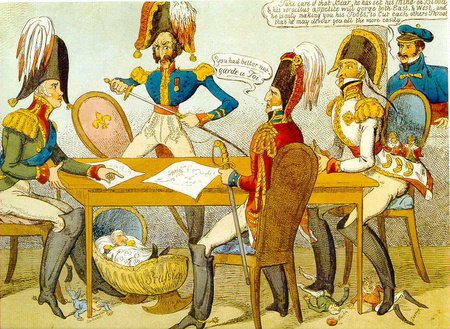

The idea of a multipolar system bound to conservative principle was a failing of the Congress of Vienna as five distinguished countries bound to a common goal was little more than a quixotic ideal. The reluctance to incorporate less potent nations, such as Spain, Portugal or Greece, in the Congress System also reduced collaboration between countries. The Congress of Verona (1822) was the last of the Quintuple Alliance conferences [10], and the Holy Alliance also diminished [11] following Tsar Alexander I's death in 1825.

There was an inherent conflict of interest between the five great powers; they each had distinct principles and approaches to foreign policy. The United Kingdom and France adopted a policy of European isolationism for most of the first half of the nineteenth century, whilst the Holy Alliance powers intervened capriciously when they had an incentive to, not when they deemed it best for the Concert of Europe’s sake. For instance, Russia intervened in the Greek War of Independence to defend Greek nationalism despite being a member of the Holy Alliance intended to uphold the conservative status quo. The conservative principles enunciated in the Congress of Vienna seemed to collapse in the 1830 London Conference. The great powers acquiesced to Belgian demands and granted them independence from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands—another recognition of the right to self–determination [9], contradicting their aims.

The idea of a multipolar system bound to conservative principle was a failing of the Congress of Vienna as five distinguished countries bound to a common goal was little more than a quixotic ideal. The reluctance to incorporate less potent nations, such as Spain, Portugal or Greece, in the Congress System also reduced collaboration between countries. The Congress of Verona (1822) was the last of the Quintuple Alliance conferences [10], and the Holy Alliance also diminished [11] following Tsar Alexander I's death in 1825.

Cartoon illustrating the Congress of Verona between the five European great powers: the five delegates seem to be in discord on the course of action to take regarding continental affairs, the bystander warns them that the Franch representative is beguiling them into intervening on his behalf, the dolls on the floor—symbols of less powerful European nations—are trampled on by the major powers

Monarchical Restoration

As part of the great powers’ traditionalist mission, The Congress of Vienna restructured the administration of several European states to favour monarchism—especially that absolute. The Bourbon Restoration in France under the First Treaty of Paris (1814) is the most notable instance. To reestablish France as a constitutional monarchy under the conservative Bourbon dynasty, preferable to a republic—the French style of government since 1792 [12]—Louis XVIII was imposed as king, and the Charter of 1814 was granted to devolve some administrative powers to the National Assembly.

The Bourbon dynasty was also restored in Naples, ruled by Joseph Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. The Austrian House of Habsburg was reinstalled in the Italian duchies of Parma and Modena, and Venice—previously a republic [13]—was merged into Austria. This temporarily halted the flourishing of constitutional monarchies in Europe; former client states of the First French Empire were deprived of the Napoleonic Code, which bestowed some civil liberties, legal reform and judicial equitability.

King Louis XVIII of France: the Bourbon successor to Emperor Napoleon I, ascending to the throne by the First Treaty of Paris in an attempt to preserve the ancien régime in France

The restoration of the ancien régime in Europe also misfired—conservatism could no longer be the leading political doctrine after a decades-long exposure to liberalism and constitutionalism during the Napoleonic Wars. The principles enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen had also been disseminated throughout Europe and citizens demanded their recognition.

By late 1820, many nations had erupted into anti–monarchist revolutions. In Spain, the Trienio Liberal emerged as a military uprising against King Ferdinand VII; in the Two Sicilies, the Revolution of 1820–21 briefly dethroned King Ferdinand I and in Russia, the Decembrist Revolt of 1825 aimed at the establishment of a constitutional monarchy. However, all these revolutions were quelled by military force—some by foreign intervention from the great powers.

Nonetheless, the Concert of Europe’s attempt to perpetuate the doctrines of divine right and absolutism—widely perceived as obsolete—proved fruitless: the Royal Statute of 1834 permanently instated a bicameral legislature in Spain, the Two Sicilies were merged into the constitutional Kingdom of Italy in 1861 after the Risorgimento, Russia eventually abolished Tsardom in 1917, and the Bourbon dynasty was expunged from France after the July Revolution of 1830.

By late 1820, many nations had erupted into anti–monarchist revolutions. In Spain, the Trienio Liberal emerged as a military uprising against King Ferdinand VII; in the Two Sicilies, the Revolution of 1820–21 briefly dethroned King Ferdinand I and in Russia, the Decembrist Revolt of 1825 aimed at the establishment of a constitutional monarchy. However, all these revolutions were quelled by military force—some by foreign intervention from the great powers.

Nonetheless, the Concert of Europe’s attempt to perpetuate the doctrines of divine right and absolutism—widely perceived as obsolete—proved fruitless: the Royal Statute of 1834 permanently instated a bicameral legislature in Spain, the Two Sicilies were merged into the constitutional Kingdom of Italy in 1861 after the Risorgimento, Russia eventually abolished Tsardom in 1917, and the Bourbon dynasty was expunged from France after the July Revolution of 1830.

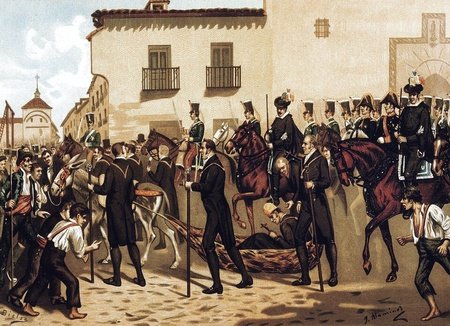

The Trienio Liberal in Spain (1820–1823): after having the absolutist Ferdinand VII restored as King following the Napoleonic Wars, citizens demanded the Constitution of 1812, which acknowledged several liberal principles such as popular sovereignty, freedom of the press and separation of powers, to be reinstated, but the revolution failed owing to military intervention from France

Assessment

The Congress of Vienna set a precedent for nineteenth-century European diplomacy, yet the conservative, traditionalist utopia envisioned by the delegates collapsed as quickly as it was restored. Its preeminent goal—preserving continental peace through redrawing borders—was largely actuated, as multiple powers would not engage in war for nearly forty years. However, it failed to acknowledge the intensity of liberal and nationalistic sentiment among populaces following the diffusion of French Revolutionary ideals; no level of restraining liberalism, constitutionalism and nationalism could prevent the continent from erupting into sporadic revolts throughout the nineteenth century. In his book Metternich and Austria: An Evaluation, historian Alan Sked criticises the delegates, such as Prince Metternich, for preventing Europe from 'developing along "normal" liberal and constitutional lines'. The congress’ very style of diplomacy—multipolar concordance between great powers based on one ideology (conservatism)—was idealistic and unpragmatic as nations had different priorities and approaches to foreign policy.

Whilst synonymous with reactionary politics, historians generally agree that the Congress of Vienna saw the birth of modern diplomacy. Historian Mark Jarrett argues that ‘Europe was ready […] to accept an unprecedented degree of international cooperation’; the collaboration between multiple powers towards a common aim posited in the congress would serve as the model for the League of Nations, the United Nations and the European Union. Whilst many of the representatives had somewhat antiquated views about governance and politics, ironically, the Congress of Vienna shaped the structure of the modern world.

Notes

[1] The War of the Seventh Coalition is also known as the Hundred Days—Napoleon's return to France from exile in Elba to reconstruct the First French Empire.

[2] The delegates listed are the most notable, but not only, ones in the Congress of Vienna from their respective countries; there were twenty-three delegates. Furthermore, there were representatives from other nations, such as Sweden and Portugal, but the great powers virtually entirely determined the course of action.

[3] The French Revolution's ideals may have been liberal and democratic, but these were arguably not fulfilled. For more information, consider consulting my blog on the subject.

[4] In this blog's context, ancien régime (French for "old order") refers to the conservative status quo before the 1789 French Revolution, characterised by absolutism and stringent conservatism.

[5] Figures of deaths (distinct from casualties) vary greatly, but historians generally deem it between three-and-a-half million and seven million. In modern history, this was only (possibly) surpassed by the Thirty Years' War, with four to eight million deaths. From ancient history, only the Roman civil wars in the first century BCE potentially superseded the Napoleonic Wars' death count, with over three million deaths. For more information, considering consulting these sources: "Napoleonic Wars casualties" and "List of wars by death toll", although they may not be fully reliable.

[6] For more information about Francisco Goya, consider consulting this source, and for more information about his prints The Disasters of War, consider consulting this source. (JetPunk does not allow hyperlinks on pictures' captions)

[7] Piedmont, which was in union with the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1720 to 1861, is also known as "Sardinia", "Piedmont-Sardinia" or "Sardinia-Piedmont".

[8] The Quadruple Alliance had already de facto been formed in 1813 to counter the First French Empire, but it was officially ratified in 1815.

[9] In this context, self–determination is a fundamental nationalistic tenet denoting a populace's right to form their own nation depending on their will; Belgians exercised it as they seceded from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830. The Concert of Europe did not recognise its legitimacy, deeming it a "revolutionary" principle which had to be eradicated. However, the great powers felt forced to acquiesce to the Belgians' demand since it was no longer practical to unite them and the Dutch under one state. For instance, the former were mostly Catholic whereas the latter were generally Protestant. This illustrates the unpragmatic nature of the Concert of Europe in being bound to a set of fixed principles.

[10] The Quintuple Alliance was never officially dissolved, but the five great powers would not regularly convene again after the early 1820s. After the five initial congresses: Vienna (1815), Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), Troppau (1820), Laibach (1821) and Verona (1822), the Concert of Europe convened irregularly and much less frequently.

[11] Again, the Holy Alliance was never officially dissolved, but being the conception of the pious Tsar Alexander I, it became defunct after he died in 1825.

[12] Whilst France did not officially have a king from 1792 to 1814 (before Louis XVIII's ascension), Napoleon virtually had absolute power under the Constitution of the Year VIII, especially once he crowned himself emperor in 1804. Parallels could be drawn to the English Interregnum; whilst Oliver Cromwell was officially "Lord Protector", he ruled like a king, and his role was even hereditary as his son Richard rose to power upon his death in 1658.

[13] Prior to the French Revolutionary Wars, Venice had been an oligarchical republic since 697 CE. Napoleon Bonaparte conquered it in 1797; it became integrated into the Kingdom of Italy (a French client state) in 1805.

[14] For more information about the principles enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, consider consulting my blog on the French Revolution.

Further Reading

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories. The links appearing throughout the blog should also be consulted.

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

- Establishment of the National Assembly

- Constitutionalism in the French Revolution

- Republicanism in the French Revolution

- Robespierre's Reign of Terror

- The Directory

- French Revolutionary Wars

- Timeline of the French Revolutionary Wars

- The Directory

- Biography of Napoleon Napoleon's Rule

- Society in the Napoleonic Era

- Aims of the Congress of Vienna

- Diplomats of the Congress of Vienna

BALANCE OF POWER

- Analysis of Balance of Power

- Historical Overview of Balance of Power

- Balance of Power in the Congress of Vienna

- Territorial Changes in the Congress of Vienna

- Achievements of the Congress of Vienna

MULTIPOLARITY AND ALLIANCES

- Overview of Multipolarity

- Multipolarity and the Congress of Vienna

- Alliances in the Congress of Vienna

MONARCHICAL RESTORATION

- The Bourbon Restoration

- Overview of the Habsburgs

- Revolutions in the Early 1820s

- Spain Under King Ferdinand VII

- The Decembrist Revolt

ASSESSMENT

- Metternich and Austria: An Evaluation by Alan Sked

- Quotes from the Wikipedia article "Historical assessment of Klemens von Metternich"

- Quotes from the Wikipedia article "Congress of Vienna"

MISCELLANEOUS

- Overview of the Congress of Vienna (1)

- Overview of the Congress of Vienna (2)

- Peace Diplomacy and the Congress of Vienna

- The Congress of Vienna: Origins, processes and results by Tim Chapman

- Securing Europe After Napoleon: 1815 and the New European Security Culture by Ido de Haan, Brian Vick and Beatrice de Graaf

SELF–PUBLISHED SOURCES

SUGGESTED VIEWING

- The Congress of Vienna by Historia Civilis (1)

- The Congress of Vienna by Historia Civilis (2)

- Post–Napoleonic Europe by CrashCourse

- The Congress of Vienna, lecture from Columbia University

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning CONCERT OF EUROPE. The rest can be accessed from my History series.

Your approach to blogs is very interesting — the narrative a la historical work, a large number of footnotes at the end and the lack of personal perception makes your blogs very different from others. And it's not bad, on the contrary, it's even great that you have such a personal style! Anyway, I'm waiting for more blogs from you

nice blog as usualy tho!