Did the French Revolution Reach its Aims?

Blog by

First published: Monday February 19th, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Monday February 19th, 2024

Report this blog

+2

This blog shall provide an academic overview of whether the French Revolution's objectives were fulfilled with time.

It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article.

It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary. For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms or events not covered in detail in this article.

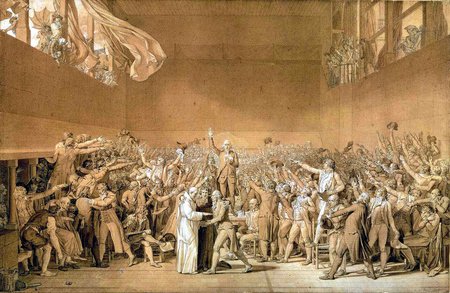

The Tennis Court Oath, establishing the National Assembly: the first governing body of France committed to fulfilling the citizens' needs

Overview

The French Revolution was the first populist revolt in Europe, motivated purely by the people’s demands for better living conditions and more liberties. From its inception on 14th July 1789, revolutionaries ambitiously endeavoured to pass reforms improving citizens' political and social conditions. Whilst not fully achieved during the Revolution, its aims at enforcing and propagating liberalism, democracy and nationalism were eventually fulfilled in France, especially throughout the nineteenth century.

Democracy

The concept of a democratic government committed to the people’s exigencies – supposedly ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’ (Abraham Lincoln) – and expunging authoritarianism and special favours materialised in the 1870s. Following the Tennis Court Oath on 20th June 1789, the National Assembly usurped many of King Louis XVI’s powers and became the effective French governing body. Most of the representatives were bourgeoisie members (hence, the Third Estate), reflecting the population of the country, 98% of which comprised Third Estate citizens; Abbé Sieyes considered them to be ‘nothing in the political order’, desiring to ‘become something’ (‘Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État’). In representing their interests, the Assembly became the first democratic government in Europe. Popular sovereignty became predominant, such that the monarchy, seen as despotic, was abolished on The monarchy was finally abolished on 21st September 1792. The Constitution of Year III, establishing the Directory in 1795, also implemented many checks and balances and division of powers, mindful of eliminating any potential autocracy.

Due to the dictatorial regimes in the Napoleonic Era and following the Bourbon Restoration, it would take until the French Revolution of 1848 for their first direct election for a leader with universal male suffrage; free presidential elections (which were ‘indirect’ until 1965) were held from 1873. The Revolution also encouraged other European peoples to protest their absolute monarchies, replaced with democracy. France would not abandon autocracy until 1870 – when Emperor Napoleon III was deposed following its poor performance in the Franco-German War, and the Third Republic was proclaimed – with Adolphe Thiers as its first ‘true’ president.

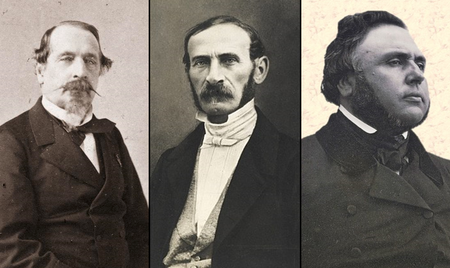

The three main candidates of the 1848 French presidential election (left to right): Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis-Eugène Cavaignac, Alexandre Ledru-Rollin: the first French election with universal male suffrage - a consequence of political reform favouring democracy

Nationalism

Nationalism – the collectivist movement uniting people of a particular culture (especially language) under one nation and synchronising government function with bolstering the nation – arose from the French Revolution and morphed nineteenth-century European history. As delineated in Article III of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – “The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation” – the ‘nation’ refers to the country’s citizens (in this case, France), which the government was to be responsible for safeguarding. Disseminating through the Napoleonic Wars – such as with the agglomeration of most German states within the Holy Roman Empire into one (Confederation of the Rhine) – European folk sought to form new nations based on a common identity, ethnicity, language or religion.

1821 saw the first display of nationalistic sentiment, as Greeks revolted against the Ottoman Empire and fully gained independence in 1830. Greece’s success in pursuing nationalism encouraged ethnic Germans to demand the creation of a united Germany (same for Italians), and ethnic Austrians, Hungarians, Croats, Slovenes, et cetera to splinter from the Austrian Empire. Eventually, Italian and German Unification occurred in 1871, and Austria-Hungary was dissolved in 1919, fostering the creation of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the Great Eastern Crisis – a series of Balkan uprisings within the Ottoman Empire – stimulated the independence of Romania (1877), Bulgaria (1878, partially) Serbia (1878, fully), and later other nations during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. These independence movements stemmed from the proliferation of nationalism during the French Revolution.

The Expedition of Thousand: a key event in the Italian Wars of Unification - a consequence of the nationalism propagated by the French Revolution

Liberalism

The French Revolution’s primary accomplishment – promulgating and mandating liberal principles to safeguard every citizen’s rights – was gradually realised throughout time. Shortly after the National Constituent Assembly’s formation, the August Decrees – issued in August 1789 – rescinded the feudal system and any privileges previously borne by the First and Second Estates and strictures on the Third Estate, meaning that no formal financial or social distinctions between social classes could be made. They preceded the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – a keystone document of the Enlightenment liberal ideals, guaranteeing “liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression” to every ‘man’ (Article II) – deemed equal and free agents. For instance, the rights to private property, free speech, freedom of the press, prevention from arbitrary arrest and equality before the law were granted. Whilst mandated in the Constitution of 1791, these liberal ideals were not extensively enforced throughout the Revolution due to state authoritarianism or inactivity.

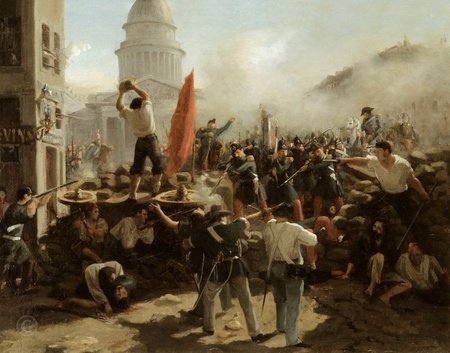

Following mass dissatisfaction with the Orléanist regime, French citizens revolted again in 1848, demanding workers’ rights, price stability, and, above all, a democratic government. Although delayed by Napoleon III’s dictatorial rule from 1851 to 1870, the Third and Fourth Republics would enact significant reforms to materialise the liberalism envisioned by the French Revolution (1789). For instance, egalitarianism was acknowledged; women gained suffrage in 1945, and the principle of gender equality was introduced in the 1946 Constitution. That same constitution would grant every citizen equal citizen “with no distinction as to race”; the most considerable prior reform in racial equality was the abolition of slavery in 1848. Furthermore, the strict separation of church and state (secularism) was mandated in 1905, and freedom of the press was fully granted with the passage of the Press Law of 1881.

The French Revolution of 1848: establishing a democratic government (temporarily) to enact liberal reforms

Conclusion

The French Revolution’s objectives in granting citizens more political representation, fostering nationalism throughout Europe and enacting liberal reforms to mandate fundamental human rights shaped nineteenth-century European history. As the Age of Revolutions progressed, these ideals were realised as France passed legislation to effect such reforms, and ethnic groups revolted to form new nations representing their identity.

Further Reading

This blog is part of a set concerning the FRENCH REVOLUTION. The rest can be accessed from my History series, listed consecutively as the first category of blogs.