Is Morality Absolute?... according to Socrates

Blog by

Last updated: Friday February 2nd, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Friday February 2nd, 2024

Report this blog

+5

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of Socrates' notion of moral absolutism. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Socrates: one of the most prominent proponents of moral absolutism in Ancient Greece

Overview

Socrates was born in 469 BCE in Athens during the zenith of the Athenian Golden Age: a period in the fifth century BCE marking the city-state’s cultural supremacy regarding the flourishing of its literature, architecture, politics, military and philosophy. He periodically attended political discussions in the Ecclesia and later became an established presence in philosophical debate. To shape such debate, Socrates intended to approach an unambiguous notion of knowledge. Among this, he sought a universal ethical system, which he believed was the sole one and applied in every scenario, and that anyone can live by – donning him the label of a ‘moral absolutist’.

Theory of the Soul

Socrates’ theory of the soul is the epicentre on which his doctrine of moral absolutism – that absolute ethics and knowledge exist – are based. Inspired by Heraclitus, he believed that the physical world is in a "state of flux" – distinct from the ideal one comprising the immutable universal values such as wisdom, beauty, and morality (collectively referred to as the ‘Truth’). The soul is an immortal segment of the ideal world: it is the ‘gateway’ through which humans can comprehend the objective Truths. It must be maintained through evaluating one’s knowledge – as wisdom and virtue are interdependent. Hence, Socrates held that there was an objective ethical path one must follow to fulfil the soul. This is gradually manifested upon accumulating sufficient expertise on how to act accordingly and scrutinising one’s behaviour. This is represented in the adage:“The unexamined life is not worth living”, signifying that, without ‘examining’ one’s conscience and questioning his ethics (safeguarding his soul), he cannot approach the moral truth.

Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus: whose theory of 'flux' influenced Socrates' theory of the soul

'The Good Life'

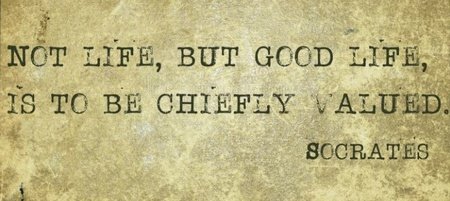

Socrates’ concept of ‘The Good Life’ is also built on his moral absolutism – that knowledge leads one to find the principles of righteousness. His aphorism: "Not life, but good life, is to be chiefly valued" indicates that every human intrinsically acts to maximise his delectation. Therefore, felicity can be prescribed as the end goal in life. The means to be content is seeking the moral truth via evaluating what one knows about ethics. Since morality is interconnected with knowledge, acting rationally and logically assessing one’s beliefs and behaviour will invariably guide him to a fulfilling existence. Since virtue and knowledge are equated, a similar connection can exist for vice; for instance, some break the law for personal gain. Socrates accentuates the difference between a factually good action and one that merely appears to be so – one that causes superficial happiness but does not benefit the soul. Hence, vice is induced by a misconception: a lack of knowledge (ignorance). For example, a thief may commit theft with the intention of self-gratification, but – being an immoral action – it does not sustain the soul; hence, it does not actually indulge the person. Acting decorously and prudently can be done by analysing one’s knowledge of ethics to arrive at the objective Truth.

A visual representation of Socrates' aphorism regarding 'The Good Life'

Counterarguments to Moral Absolutism

Socrates’ notions seem anathema to the Sophists' relativism – which, in fact, exhibited one of his intentions as a philosopher. He was one of their most vociferous opponents – repelling their notions that morality and knowledge are relative to the individual's senses and that language is the determining factor of a trenchant argument. The contradiction in the Sophists’ notion was highlighted by many: if the truth depended on the individual, everyone would be accurate in his beliefs, making discussion and education infeasible. Despite vilifying them for their solipsism, hypocrisy, and exorbitant fees, they converged on their shared sceptic attitude – none sufficed with intuitively accepting social customs and leaving thoughts and authority unquestioned. This outlook wrought Socrates' allegations of being aligned with Sophistry – more specifically, of subverting Athenian youths with orders to challenge the gods’ veracity. The irony in having Socrates deemed a Sophist was particularly acerbic considering their bifurcation concerning the issue of the nature of morality.

The three most influential Sophists (from left to right): Protagoras, Thrasymachus and Gorgias: opponents to Socratic thinking

Conclusion

Socrates defined himself as a moral absolutist by proclaiming the existence of an omnipresent moral system – determining how one should act. He taught that our soul must be preserved by acquiring wisdom about how to act and think, and this knowledge would correlate with a better understanding of virtue. Since living virtuously is necessary to fulfil the soul and be gratified, acting in accordance with the moral truth leads to his idea of a ‘Good Life’.

Further Reading

This blog is part of a set concerning the ETHICS AND THE GREEK PHILOSOPHERS. The rest can be accessed from my Philosophy series, listed consecutively as the first category of blogs.