How to Actually Become Wiser... according to Socrates

Blog by

Last updated: Friday February 2nd, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Friday February 2nd, 2024

Report this blog

+2

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the causes of Socrates' notion of how we can attain knowledge. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Socrates at his trial, being administered a fatal dose of hemlock. His quest for knowledge ultimately led to his demise.

Overview

Socrates was born in 469 BCE in Athens during the zenith of the Athenian Golden Age: a period in the fifth century BCE marking the city-state’s cultural supremacy regarding the flourishing of its literature, architecture, politics, military and philosophy. He periodically attended political discussions in the Ecclesia and later became an established presence in philosophical debate. To shape such debate, he implemented the Socratic Method to reach unambiguous solutions about subjects – prompting further knowledge on the ‘Truth’.

Theory of the Soul

Socrates’ theory of the soul is the epicentre on which his doctrine of moral absolutism – that absolute ethics and knowledge exist – are based. Inspired by Heraclitus, he believed that the physical world is in a "state of flux" – distinct from the ideal one comprising the immutable universal values such as wisdom, beauty, and morality (collectively referred to as the ‘Truth’). The soul is an immortal segment of the ideal world: it is the ‘gateway’ through which humans can comprehend the objective Truths. It must be maintained through evaluating one’s knowledge – as wisdom and virtue are interdependent. Socrates held that the most cogent method to source wisdom is a deliberate dialectic between two individuals. This is known as the Socratic Method, serving as a means to facilitate the deduction of knowledge – leading to the fulfilment of the soul.

Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus: whose theory of 'flux' influenced Socrates' theory of the soul

The Socratic Method

The dialectic was an intense, elaborate conversation which Socrates carried out with common people in the street to better their logical capabilities. He stated that “[he] cannot teach anyone, [he] can only make them think”, implying that the objective of this exercise was to refine the public’s thought process. The dialogue commences with a general discussion of a concern, theory, or observation, and gradually becomes more specific – with the scope of reaching a factual definition of the related issue. Rigorous queries are then raised on the details of the argument to make it explicit and consistent with other applications. Socraic irony is employed to ensure the accuracy of the knowledge being referenced – typically taking the form of a broad question, such as what justice is. Elenchus was another integral part of the process – rooting out contradictions in the argument to create a unified theory. Moreover, to extract a complete understanding, Socrates would pretend to be ignorant about a subject and ask for elaborate explanations on the subject; this could correct incomplete or inaccurate notions.

The Socratic Method customarily does not culminate in a fixed definition of the topic at hand but resolves many pertinent inconsistencies or misinterpretations. Akin to Zen Buddhism, it results in one’s perception of his existing knowledge altering – leading him to the blunt realisation of the magnitude of aspects he is yet to learn. Socrates’ mantra that “The only true wisdom is in knowing that you know nothing” reflects the significance of committing oneself to refining his outlook on subjects, with the scope of edging closer to the Truth. An example is Socrates’ confrontation with Euthyphro as charges of the former’s impiety emanated. The latter had prosecuted his father over a similar charge, so Socrates assumes that he is an expert in holiness – which he concurs with. However, after numerous failed attempts at defining the concept, such as stating that holiness is an act agreeable to the gods – which Socrates negated by mentioning the frequent quarrels between them – Euthyphro feels coerced to concede. The dialogue was effective in sourcing factual information.

Socrates practising his method of dialectic with other Athenians

Counterarguments to Socratic Thinking

Socrates’ notion of moral absolutism is anathema to the Sophists' relativism – whose tenants boast the most formidable challenge to Socratic thought. Whilst both parties converged on their sceptic attitude (which, in fact, wrought allegations against Socrates of being aligned with Sophistry), they diverged on their ideas of the state of knowledge. Protagoras – the most influential Sophist – defined their relativistic thought in the statement: “Man is the measure of all things, of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are not, that they are not” – meaning that the individual is the unchanging source of value and knowledge, rather than a deity or moral code. This premise applies to any anatomical mechanism, from sensations to rudimentary qualities, such as justice, beauty, and morality. Other Sophists – most prolifically, Gorgias – were more radical in their outlook. He claimed that since knowledge cannot be comprehended nor communicated due to the limitations of one’s senses and language, there is no knowledge – moral nihilism. Socrates countered the Sophists’ relativism by indicating its contradictive nature: if the truth depended on the individual, everyone would be accurate in his beliefs, making discussion and education infeasible.

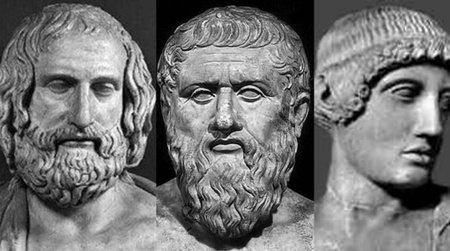

The three most influential Sophists (from left to right): Protagoras, Thrasymachus and Gorgias

Conclusion

The Socratic Method is an effective means to comprehend objective aspects of societal values: the ‘Truth’. Through methodical dialogue, this leads to deductively concluding a universal definition of an object, bringing one closer to discovering the ’Truth’ about the relevant matter. Whilst opposed by the relativistic Sophists, Socrates held that absolute virtues exist, which one can arrive at through extensive questioning, leading to a fulfilling existence. This is best represented in his adage: “The unexamined life is not worth living”.

Further Reading

This blog is part of a set concerning the ETHICS AND THE GREEK PHILOSOPHERS. The rest can be accessed from my Philosophy series, listed consecutively as the first category of blogs.